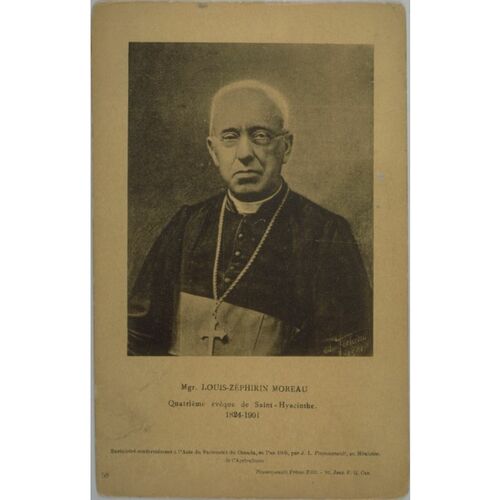

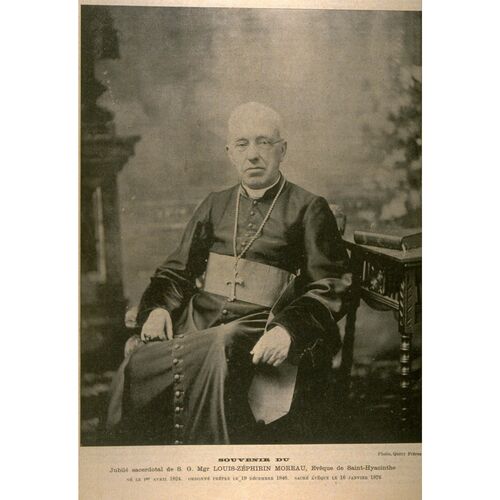

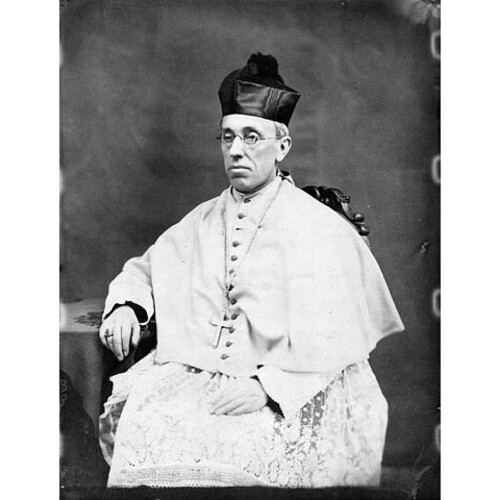

MOREAU, LOUIS-ZÉPHIRIN, Roman Catholic priest and bishop; b. 1 April 1824 in Bécancour, Lower Canada, son of Louis-Zéphirin Moreau, a farmer, and Marie-Marguerite Champoux; d. 24 May 1901 in Saint-Hyacinthe, Que.

Louis-Zéphirin was the fifth in a family of 13 children, 11 of whom reached adulthood. Not favoured by nature, he was born premature, delicate, sickly, and homely, but he did have certain gifts of intelligence. His parents felt he was unsuited for farm work, and on the advice of parish priest Charles Dion they pushed him to study, first in Bécancour, where he learned Latin under the schoolteacher Jean Lacourse, and then from 1839 to 1844 at the Séminaire de Nicolet. In May 1844, on the completion of his classical studies, the authorities in the seminary immediately asked him to replace the teacher of the fourth form (Poetry), who had fallen ill. Upon being introduced to Archbishop Joseph Signay* of Quebec, who was making a pastoral visit to Nicolet, young Moreau was accepted as a candidate for the priesthood by Signay, who let him enter holy orders and tonsured him. That autumn Moreau accompanied his pupils into the fifth form (Belles-Lettres), and also began his theological studies.

In November 1845 fatigue forced him to leave the seminary and seek refuge in the presbytery at Bécancour, where he went on studying at a slower pace. His health had not improved much by September 1846 when he met Signay. The archbishop advised him to return home and give up the religious life. At the suggestion of Dion and his teachers at Nicolet, Louis-Zéphirin went to Montreal to offer his services, armed with their letters of recommendation. He had a meeting in secret with Bishop Ignace Bourget*, who was leaving for Europe and put him in the hands of his coadjutor, Bishop Jean-Charles Prince*. Prince immediately accepted him into the episcopal palace to have him finish his theological studies, which he kept an eye on from a distance. He moved Moreau swiftly through the various stages to ordination, conferring minor orders in October 1846, the subdiaconate on 6 December, diaconate on the 13th, and priesthood on the 19th. An examination that was judged satisfactory proved he had the requisite theological knowledge and later was the basis for the conclusion that he had received “the normal training for a priest at the time in Canada.” Although Moreau devoted himself to studying for five more months and reviewed the principal theological treatises for the examinations given young priests, he would suffer all his life from a lack of depth in theological matters.

When Bishop Bourget returned in 1847, Moreau became master of ceremonies at the cathedral and gave assistance in the secretariat (chancellery). He soon advanced from under-secretary to assistant and then titular secretary. At the same time he served as chaplain to the poor at the convent of the Sisters of Charity of Providence. On 19 Dec. 1847 the chapter appointed him chaplain of the cathedral; his duties there included looking after daily mass, preaching on Sunday, and hearing confessions. They proved too onerous, however, for an inexperienced priest, and he soon left to become the director for the community of the Good Shepherd and to resume his work at the secretariat. These years of initiation into pastoral activity and diocesan administration were crucial for the future bishop: he particularly liked communal life in the Montreal episcopal palace, and he was profoundly marked by Bourget’s spirituality – a life of meditation and prayer, devotion to the Eucharist, the Blessed Heart, and Mary, and reading the Bible – and by the strong personality of this bishop who was at the heart of the religious revival of the 1840s. As a result of his work as chaplain, the young priest was already being called “good Monsieur Moreau.”

In 1852, at the age of 28, Abbé Moreau agreed to become the principal colleague and closest adviser to the first bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe, Mgr Prince. Armed with the experience acquired in Montreal, he became secretary and chancellor to Prince, and then to his episcopal successors, Joseph La Rocque* (1860–65) and Charles La Rocque* (1866–75). In addition to this heavy load he assumed the offices of procurator for the episcopal corporation (1858–75) and secretary of the diocesan council (1869–75). He also administered the diocese during periods when the see was vacant, in 1860, 1865–66, and 1875, and during the bishop’s absence in 1862 and 1870. Furthermore, Charles La Rocque entrusted the routine administration of the diocese to Moreau when, because diocesan finances had been left in poor shape by Joseph La Rocque, “who had little concern for figures and business,” the bishop moved from his cathedral city to the presbytery in Belœil.

Despite his absorbing administrative tasks the secretary took on various pastoral roles. He was chaplain to the boarding-school run by the Congregation of Notre-Dame (1853–58), to the nuns at the Hôtel-Dieu of Saint-Hyacinthe (1859–66), and then to the Soeurs de la Présentation de Marie (1867–69). He was curé of the cathedral twice, from 1854 to 1860, when some thought his departure a sign of disgrace, and from 1869 to 1875. In 1869 he also became vicar general.

As the bishops’ right-hand man Moreau displayed a great capacity for work, order, and efficiency. According to his contemporary Alexis-Xiste Bernard, as procurator “he first had to endure the worry about the financial difficulties, and then the labour entailed by the extensive deals that were finally worked out for paying off the bishopric’s debt.” It was these financial difficulties that sent him to Paris and Rome in 1866, with somewhat limited success. As parish priest of Saint-Hyacinthe-le-Confesseur, Moreau concerned himself particularly with the workers’ lot, and in 1874 he founded the Union Saint-Joseph, a Roman Catholic mutual aid society to provide protection for members and their families from severe blows (unemployment, accidents, early death) and to strengthen their spiritual life. After a slow beginning with 75 charter-members, the association reached a size enabling it to publish a weekly paper, L’Écho, in 1891, to become the owner at the end of the century of “a handsome stone building,” and to amalgamate in 1937 with La Survivance, a mutual life insurance company.

When Charles La Rocque died on 15 July 1875, the clergy and the people spontaneously proposed vicar general Moreau as his successor. But the late bishop had warned Archbishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau* of Quebec that his vicar general had displayed too many weaknesses in administering temporal affairs and that he did not see any priest in his diocese whom he could recommend; he suggested moving Bishop Antoine Racine* from Sherbrooke to Saint-Hyacinthe. At their meeting on 21 July 1875 the bishops of the ecclesiastical province of Quebec unanimously rejected La Rocque’s proposal. Instead, they sent a terna (a recommendation) that listed Moreau, the candidate dignissimus from all points of view, far ahead of the other two candidates (Joseph-Alphonse Gravel and Jean-Remi Ouellette). This choice was ratified by the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda on 21 Sept. 1875 and Pope Leo XIII signed the appointment bulls on 19 November. Louis-Zéphirin Moreau was consecrated fourth bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe on 16 Jan. 1876.

Moreau administered the diocese for 25 years, although from 1893 he left the external administration and anything that required tiring voyages to his coadjutor, Bishop Maxime Decelles. From the outset he proved well acquainted with diocesan matters, and he set in motion a series of initiatives that were sometimes bold: reopening the episcopal palace in Saint-Hyacinthe, building a cathedral, establishing a chapter, creating an officiality and a court for matrimonial cases, and founding the Sœurs de Saint-Joseph de Saint-Hyacinthe in 1877 and the Sœurs de Sainte-Marthe in 1883. He also took several measures (holding synods, ecclesiastical conferences, and annual pastoral retreats) that enabled him to have colleagues who were better trained intellectually and spiritually. According to historian Rolland Litalien, throughout his rule this goal was his foremost concern, as he showed by his constant care for “the saintliness and happiness of his priests, the close and fraternal relations he maintained with them, his sense of collegiality, the community life that he was able to foster in his diocese between bishop, priests, religious, and laity, . . . the extraordinary impetus he gave to ecclesiastical studies among both his seminarists and his priests.”

Bishop Moreau continued the social work already in progress. He kept a close eye on the development of the Union Saint-Joseph, which from then on was extended to the whole diocese. In the farming parishes he encouraged agricultural clubs, and to combat emigration to the United States – one of the reasons his diocese declined from 120,000 faithful in 1886 to 115,000 in 1901 – he strongly supported the establishment of agricultural missionaries; he also took a keen interest in the lot of the French-speaking Catholics in New England, of whom his own brother was one. Likewise he multiplied his efforts and appeals to help Catholics in the townships of his diocese “where everything has to be created: churches, presbyteries, schools, support for the priests.” The same solicitude was shown for the poor, whom he received every Monday at the episcopal palace, and for members of his flock who had been sorely tried by fires. (Two-thirds of the town of Saint-Hyacinthe was destroyed in 1876, five parishes suffered from fires in 1880, and the Métairie Saint-Joseph, a shelter for the sick and for elderly or infirm priests, burned in 1898.) And finally, convinced of the baneful effects of drunkenness, from both religious and economic points of view, he threw the full weight of his prestige behind two temperance campaigns in his diocese, in 1880 and 1885–89.

During his 25 years of episcopal administration Moreau founded 13 parishes and 22 institutions, most of which were educational (académies, or commercial colleges). This development depended first upon his clergy, which grew from 154 priests in 1876 to 203 in 1901, but above all upon the many religious communities already established or introduced by him: eight communities of teaching brothers, seven women’s communities devoted to education or social welfare, not to mention the Dominicans and the Sisters Adorers of the Precious Blood, the former dedicated to preaching and the latter to the contemplative life. The bishop let the secular clergy run the two classical colleges, at Saint-Hyacinthe and Marieville, despite the difficulties the latter one was encountering.

In 1876 Moreau had joined an episcopacy divided by political issues such as the intervention of the clergy in elections, and by the university problem (the attitude of the Université Laval and the founding of a university in Montreal). Holding profound ultramontane convictions, even though he lived in a city reputed to be a centre of liberalism, Moreau readily sided with the suffragans, led by Bourget and Louis-François Laflèche*, in a struggle against Archbishop Taschereau; he also supported his teacher and friend Laflèche in opposing a plan to divide the diocese of Trois-Rivières. However, he used the renown of his elders and the fact that he was much younger as pretexts to remain in the background during the controversies.

Partly because of the mission of Bishop George Conroy*, the apostolic delegate sent to end the division among the episcopate and halt the intervention of the clergy in elections, and partly because of a series of decisions from Rome that were one-sidedly favourable to Taschereau’s opinions in his battle with the intransigent ultramontanes, the bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe distanced himself from the Laflèche clan and backed the archbishop and the Université Laval. He placed obedience to the pope ahead of his ideas and friendships. In the early 1880s, for example, he played an active role, particularly through numerous letters to the pope and to Propaganda, in a new campaign to divide Trois-Rivières and create the diocese of Nicolet. Despite some harsh judgements on those who did not obey Rome, he constantly sought to bring people who held opposing views together and reconcile the adversaries. In 1885, for instance, he accompanied Elphège Gravel, the first bishop of Nicolet, on a visit to Bishop Laflèche, “to calm things down and show him that there is no antipathy to him.”

The misfortunes besetting Laflèche, who was persona non grata in Rome, and the illness of Cardinal Taschereau, who had to hand over the reins of power to a coadjutor, made Moreau one of the principal spokesmen, along with Louis-Nazaire Bégin*, for the Canadian bishops. At the time of the lengthy debate on the Manitoba school question [see Thomas Greenway], he rediscovered all his ultramontane fervour and made plain his nationalist convictions. He supported unreservedly the position taken by Archbishop Adélard Langevin* of Saint-Boniface, and he multiplied his letters to politicians and to Rome (some 30 of them) to denounce the injustice being done the Roman Catholics in Manitoba. The apostolic delegate Monsignor Rafael Merry del Val drew his severe criticism for seeming “to lend his ear and his attention to the liberal priests and men of the political persuasion of the federal prime minister, Monsieur Laurier [Wilfrid Laurier*], who have taken care to circumvent him.” Moreau none the less accepted obediently the encyclical Affari vos, issued by Leo XIII on 8 Dec. 1897, and he exhorted the people of his diocese “to receive the word of the Vicar of Christ in a profound spirit of faith and feelings of intense gratitude.” On 8 Jan. 1898 he wrote to Rome that he would obey, and on 26 January he expressed his “filial gratitude” to the pope and the hope for a “happy solution to the serious question of the schools in Manitoba.”

At that time Bishop Moreau was infirm physically, even though his intellectual faculties remained unimpaired. His people saw him only in exceptional circumstances: the 50th anniversary of his ordination as a priest in 1896, and the silver jubilee of his consecration as bishop in 1901. His reputation for kindness and saintliness grew steadily, and miracles were asked of him or attributed to him. Popular veneration was manifest at his funeral in May 1901 and did not diminish with the passage of time. Thus the diocesan authorities were impelled to begin in 1925 the lengthy procedure that revealed unequivocally the exceptional virtues of this great priest: faith, charity, kindness, piety, firmness, and unworldliness. His beatification was proclaimed by Pope John Paul II on 10 May 1987.

[L.-Z. Moreau’s writings were brought together during the procedure for his beatification and are held at the Arch. de la Chancellerie de l’Évêché de Saint-Hyacinthe, Qué. The following are in manuscript: Copies des lettres du serviteur de Dieu d’après les “Reg. des lettres concernant l’administration diocésaine,” expédiées de l’évêché de Saint-Hyacinthe à la Sacrée Congrégation des Rites le 2 oct. 1933; Autres copies des lettres du serviteur de Dieu, expédiées de l’évêché de Saint-Hyacinthe à la Sacrée Congrégation des Rites le 2 oct. 1933; and Statuts du chapitre de la cathédrale de Saint-Hyacinthe, 1878. The remainder are in published form: Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Saint-Hyacinthe, A.-X. Bernard et al., édit. (27v. et 370 feuillets parus, Montréal et Saint-Hyacinthe, 1893– ), vols.5 to 12, and Constitutiones synodales Sancti Hyacinths . . . (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1880).

These documents and others relating to Moreau are either reproduced or cited in: Congregatio pro Causis Sanctorum, Beatificationis et canonizationis servi Dei Ludovici Zephyrini Moreau, episcopi Sancti Hyacinthi; peculiaris congressus super virtutibus die 6 octobris 1970; relatio et vota, A. M. Larraone, reporter (Rome, 1970); Canonizationis ven. servi Dei Ludovici Zephyrini Moreau, episcopi Sancti Hyacinthi (1824–1901); positio super miraculo (Rome, 1986); Canonizationis ven. servi Dei Ludovici Zephyrini Moreau, episcopi Sancti Hyacinthi (1824–1901); relatio et vota congressus peculiaris super mir die 13 junii an. 1986 habiti (Rome, 1986); Officium Historicum, Beatificationis et canonizationis servi Dei Ludovici Zephyrini Moreau, episcopi Sancti Hyacinthi (†1901); peculiaris dilucidationes ex officio concinnatae (Rome, 1972); Sacra Rituum Congregatione, Beatificationis et canonizationis servi Dei Ludovici Zephyrini Moreau, episcopi S. Hyacinthi; positio super introduction causae, Adeodato Piazza, reporter (Rome, 1952); and Beatificationis et canonizationis servi Dei Ludovici Zephyrini Moreau, episcopi S. Hyacinthi; positio super virtutibus, A. M. Larraone, reporter (Rome, 1967).

The archives of almost all the archdioceses and dioceses in Canada possess files which can illustrate some aspect or other of Bishop Moreau’s life but the richest source of information is the Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), especially the following series: Acta, vol.243; Nuova serie, vols.240–42; and Scritture originali riferite nelle Congregazioni generali, vols.1004, 1044. Moreau’s birth and burial records are in ANQ-MBF, CE1-4, 1er avril 1824, and ANQ-M, CE2-1, 30 mai 1901.

Biographies of Moreau include A.-X. Bernard, “Monseigneur L.-Z. Moreau,” in Mandements, lettres pastorales et circulaires des évêques de Saint-Hyacinthe, 5: 5–25; Jean Houpert, Monseigneur Moreau, quatrième évêque de Saint-Hyacinthe (Montréal et Paris, 1986); Frédéric Langevin, Monseigneur Louis-Zéphyrin Moreau, quatrième évêque de Saint-Hyacinthe, 1824–1901 (Québec, 1937); and Rolland Litalien, Le prêtre québécois à la fin du XIXe siècle; style de vie et spiritualité d’après Mgr L.-Z. Moreau (Montréal, 1970).

Useful secondary works include the following: J.-P. Bernard, “Les fonctions intellectuelles de Saint-Hyacinthe à la veille de la Confédération,” CCHA Sessions d’études, 47 (1980): 5–17; J.-A.-I. Douville, Histoire du collège-séminaire de Nicolet, 1803–1903 . . . (2v., Montréal, 1903); A[ugustin] Leduc, “Notes historiques (1854–1913),” Saint-Hyacinthe et la tempérance (1854–1913) (Saint-Hyacinthe, 1914), 22–24; Rolland Litalien, “Se mettre à l’écoute du bienheureux Mgr Moreau,” L’Église canadienne (Montréal), 20 (1986–87): 525–28; Roberto Perin, “La raison du plus fort est toujours la meilleure: la représentation du Saint-Siège au Canada, 1877–1917,” CCHA Sessions d’études, 50 (1983): 99–117; J.-J. Robillard, “Histoire du collège Sainte-Marie-de-Monnoir (1853–1912),” CCHA Sessions d’études, 47: 35–53; and Nive Voisine, “La création du diocèse de Nicolet (1885),” Les Cahiers nicolétains (Nicolet, Qué.), 5 (1983): 3–41; 6 (1984): 147–214; Louis-François Laflèche, deuxième évêque de Trois-Rivières (1 vol. paru, Saint-Hyacinthe, 1980– ); and “Rome et le Canada: la mission de Mgr Conroy,” RHAF, 33 (1979–80): 499–519. n.v.]

Cite This Article

Nive Voisine, “MOREAU, LOUIS-ZÉPHIRIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moreau_louis_zephirin_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/moreau_louis_zephirin_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Nive Voisine |

| Title of Article: | MOREAU, LOUIS-ZÉPHIRIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |