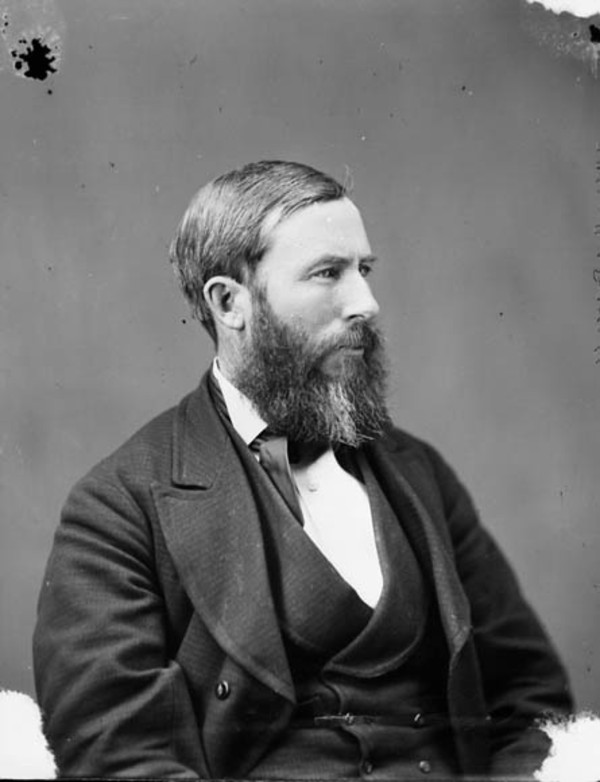

McDOUGALL, JOHN LORN, businessman, politician, and civil servant; b. 6 Nov. 1838 in Renfrew, Upper Canada, son of John Lorn McDougall* and Catharine Cameron; m. 7 Sept. 1870 Marion Eliza Morris, and they had five daughters and six sons; d. 15 Jan. 1909 in Ottawa.

John Lorn McDougall attended the High School of Montreal and then the University of Toronto, from which he graduated in 1859 with the gold medal in mathematics and the silver in modern languages. He returned to Renfrew and entered the mercantile, lumbering, and milling business of his father. McDougall Sr died in 1860, leaving John in charge of an extensive estate at the age of 21.

Influenced perhaps by his father’s long involvement in public office, McDougall served as reeve of Renfrew (1865, 1867, 1873); in 1867 he was warden of Renfrew County. In addition, he chaired the village’s school board. A Liberal in politics, McDougall was mpp for Renfrew South (1867–71) and mp for the same constituency (1869–72, 1874–78). His parliamentary career was not distinguished; only his introduction of bills, both provincial and federal, requiring compulsory voting are remembered.

In the lumber business McDougall prospered for a time. With a partner, he started an operation on the Rivière Dumoine in Quebec in 1869. Successful to begin with, it did not last through the depression of the 1870s and failed in 1878. McDougall found himself with a mother, a wife, and a young family to support, a bankrupt lumber business, an encumbered estate, and no job. His only asset, but it was a valuable one, was his loyal service to the Liberals. By happy coincidence Alexander Mackenzie*’s Liberal government in Ottawa had a job opening.

There were a number of reasons why Mackenzie chose to create an independent auditor general in 1878. John Langton*, who had been auditor since confederation and deputy minister of finance since 1870, was nearing 70 years of age. His failure to disclose that Sir John A. Macdonald* had retained control of secret service funds after he ceased to be prime minister, made him unacceptable to the Liberals. His responsibilities as deputy minister often resulted in divided loyalties. Finally, in the decade after confederation, the system of government finance suffered weaknesses in administration, lapses in judgement, and questionable payments, and there was no mechanism to force reform. The Liberals therefore decided, following the imperial model, to separate the auditor general from the general financial operations of the government and give him real powers.

The Public Accounts Audit Act of 1878 gave to the auditor general authority as a controller as well as an auditor. He had the duty to confirm that all cheques issued were for purposes approved by parliament before payment was made. To ensure that he really would be independent he was given full control over his staff, a power unique within the government at that time, and was granted tenure on good behaviour. It would require a majority in both the Senate and the House of Commons to remove him. There were, however, some limitations to his powers. If the auditor general refused to authorize a payment, the minister of finance could issue a cheque if the minister of justice held that parliamentary authority did exist. The Treasury Board could also intervene to authorize payment.

McDougall was still an mp when he became auditor general on 2 Aug. 1878. He had a degree in mathematics and considerable knowledge of commercial operations, but his auditing experience was probably slight at best. This lack would have worried neither McDougall nor Mackenzie: auditing was at the low end of the necessary skills of any expert accountant. Langton had been deputy minister of finance first and auditor a long way second. McDougall inherited the audit branch of finance and some staff from the receiver general’s office. Given that he had no auditing systems in place and few experienced staff, it is not surprising that he elected to centralize the auditing function under his direct supervision and concentrate on the pre-audit or controllership part of his function. He required all requests for payments to come to his office, with appropriate documentary support.

During his first year McDougall raised a lot of dust. Though known privately for his kind-heartedness and cordiality, officially he was tenacious, jealous of his prerogatives, and tactless. In the early years he asked a lot of questions concerning authorities and procedures that had never been asked before, made suggestions for improvement, and published the work of his office in lengthy annual reports. Accustomed to casual control, many in the government service found McDougall’s obsession with detail and his constant search for more information and tighter controls exasperating. However, at least until his last years in office, there is considerable evidence that politicians and civil servants recognized the importance of his work. Certainly, the Liberal and then the Conservative government increased his salary, his establishment, and his operating budget.

Following Macdonald’s death in 1891, the Conservative government was hit with a series of scandals [see Thomas McGreevy*]. Investigations showed that businessmen routinely bribed the civil service, that the superintendent of the government’s printing bureau had levied tolls on suppliers, that deputy ministers were creating fictitious employees in order to pay overtime to their staff, and that civil servants often charged personal purchases to the government and took unauthorized leaves. From McDougall’s perspective the frauds were a disaster because he had been unable to find them, uncovering only evidence of laxness and fiscal mismanagement. Worse still, the audit office’s method of operation probably facilitated the various schemes. Though he would meet with some success in his encouragement of improvements to the systems of accounting and control, he did not have the staff to conduct departmental audits on the scale he thought appropriate. Instead, he relied on the documentation provided to his office, and as the fraud investigations showed, much of that material was false.

McDougall’s initial response was to exonerate his staff by noting that they had relied on certified documents. He then tightened up his auditing procedures. Departments that previously had had no trouble getting payments approved began to complain of delays in the audit office. Wayward departments, such as public works and inland revenue, which had a history of fighting with McDougall, simply stopped responding to his suggestions and requests. He was forced to cut off the blocks of bank credit assigned to them in order to get their attention. In addition to these problems, Ottawa was still a small place and it may be assumed that, because of the pervasiveness of fraud and bureaucratic squabbling, McDougall became completely isolated socially.

McDougall wanted the Liberals to participate more fully in the public accounts committee, as the opposition party did in the imperial parliament. But, in spite of the fact that Sir John Sparrow David Thompson*, first as Conservative house-leader and then as prime minister, allowed the committee free rein, the Liberals could not forgo publicizing the errors and mismanagement of the Conservatives. Driven to desperation by his inability to gain support for his concept of fiscal probity, in 1895 McDougall petitioned the House of Commons to form a select committee to consider his lengthy petition for reform. Much of it was critical, at least by implication, of the government, which refused the committee.

Given this background, McDougall must have seen the election of the Liberals under Wilfrid Laurier* in 1896 as his salvation. The public accounts committee, during the first session of the new parliament, set up a subcommittee to examine the relations between McDougall and the Treasury Board and more generally the audit act in respect to the auditor general, but little was achieved. McDougall gave up on the committee, which remained dominated by senior cabinet ministers. Instead, he concentrated on specific cases. Nothing changed in his antagonistic relationship with the departments. By 1899 some members of the Laurier cabinet thought that the government could not function unless Treasury Board, on decisions of the minister of justice, routinely overruled McDougall on the validity of payments.

McDougall managed to annoy and embarrass the Laurier cabinet by his handling of the Cornwall Canal contract for the supply of light and power, originally made by the Conservatives but extended by the Liberals in 1900. At the heart of this dispute was McDougall’s interpretation of section 33 of the audit act, which required the auditor general to ensure that prices charged were fair and in accordance with the contracts. In this instance the contract was redrawn to accommodate McDougall’s concerns, saving the government, he claimed, half a million dollars. The dispute was complicated by the continuing struggle over the control of public expenditure. As the civil service grew, more and more disbursements were made by departments from their bank credit, a system McDougall opposed because it removed his prepayment powers. Consequently he restricted or seriously disrupted payments within some departments.

McDougall steadily widened the areas of his investigations. The government, however, felt he was dealing with policy when he developed strong views as to where moneys should come from (current revenue or borrowings) for certain classes of expenditures. He seems to have had no understanding of the relative importance of the transactions he examined. He may, indeed, have been as close to the archetypal caricature of accountants as has ever been achieved in Canada. In one example, a civil servant, W. J. H. Ross, had taken a leave of absence to fight in the South African War, where he was killed. McDougall held up the widow’s claim for her husband’s arrears of salary on the grounds that the government had had no right to give Ross leave for such a purpose.

In 1903 McDougall suffered a stroke which left him temporarily paralysed. He apparently never recovered fully, and perhaps his condition was a factor in his conduct in 1904. At the end of the parliamentary session of 1903, the minister of finance, William Stevens Fielding*, had introduced a bill to limit the auditor general’s power to stay the replenishment of departmental bank credits. It was subsequently withdrawn, because of the election of November 1904. In the auditor general’s report tabled in March, McDougall made public his protests over the canal contract and even threatened to resign. During the election, feeling unsupported by either the government or the opposition, he turned to the electorate in a series of letters in the Toronto Globe, ending with one calling for the return of members who would support his work.

The public accounts committee met eight times in the spring of 1905 to hear from McDougall on the revision of the audit act. By this time, however, the government had had enough. Laurier made it clear that there would be no changes to the act and that McDougall’s resignation, tendered in June 1904, would be promptly accepted. McDougall resigned on 31 July 1905.

After his resignation he formed the McDougall Audit Company, to conduct audits for private corporations and municipalities. In 1906 he was appointed to a special commission inquiring into municipal corruption in Quebec City. In spite of recurring spells of paralysis, he carried on at his usual pace. He suffered a final stroke on 12 Jan. 1909 and died three days later at his home in Ottawa.

Despite the many difficulties he had generated, McDougall had managed to command some respect from his opponents, who understood that being an effective auditor general meant being unpopular. On the recommendation of the Liberals he was created a cmg in 1897. Recognition also came from the University of Toronto, which awarded him an ma in 1882, elected him to its senate in 1901, and gave him an honorary doctorate three years later.

As auditor general of Canada for 27 years, McDougall, often without official support, had made considerable steps forward in establishing parliamentary control of public finance. In the opinion of historian Norman Ward, he laid the foundations of a thorough system of audit that would last until the 1930s and a method of reporting to the commons that would survive even longer.

Ottawa Evening Journal, 15 Jan. 1909. Renfrew Mercury and County of Renfrew Advertiser (Renfrew, Ont.), 22 Jan. 1909. R. L. Borden, Robert Laird Borden: his memoirs, ed. Henry Borden (2v., Toronto, 1938), 1: 129–30. Can., House of Commons, Journals, 1882–1905, app., reports of the standing committee on public accounts, 1881–1904 (esp. 1905, app. no.3g); Parl., Sessional papers, 1880–1905, reports of the auditor general, 1879–1904. Canadian annual rev. (Hopkins), 1901–4. Canadian biog. dict. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Illustrated atlas of Lanark County, 1880; illustrated atlas of Renfrew County, 1881 . . . , ed. Ross Cumming (Port Elgin, Ont., 1972), originally pub. as Lanark and Renfrew supps. to Illustrated atlas of the Dominion of Canada . . . (Toronto), 1880 and 1881 respectively. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell), vol.1. Norman Ward, The public purse: a study in Canadian democracy (Toronto, 1962).

Cite This Article

Philip Creighton, “McDOUGALL, JOHN LORN (1838-1909),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcdougall_john_lorn_1838_1909_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcdougall_john_lorn_1838_1909_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Philip Creighton |

| Title of Article: | McDOUGALL, JOHN LORN (1838-1909) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |