Source: Link

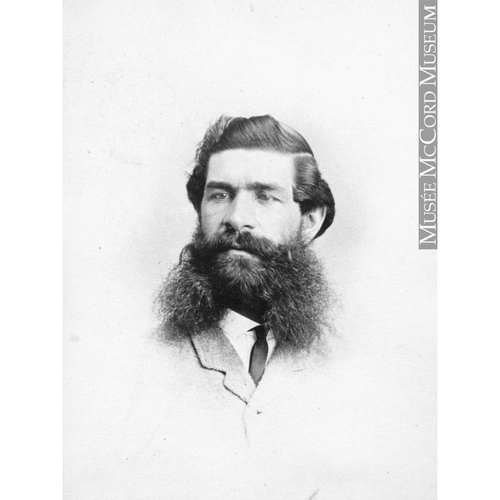

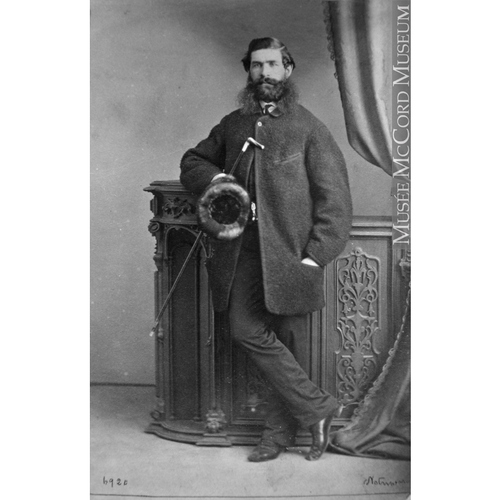

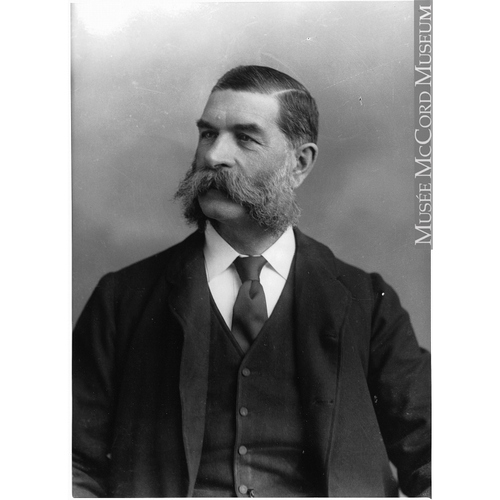

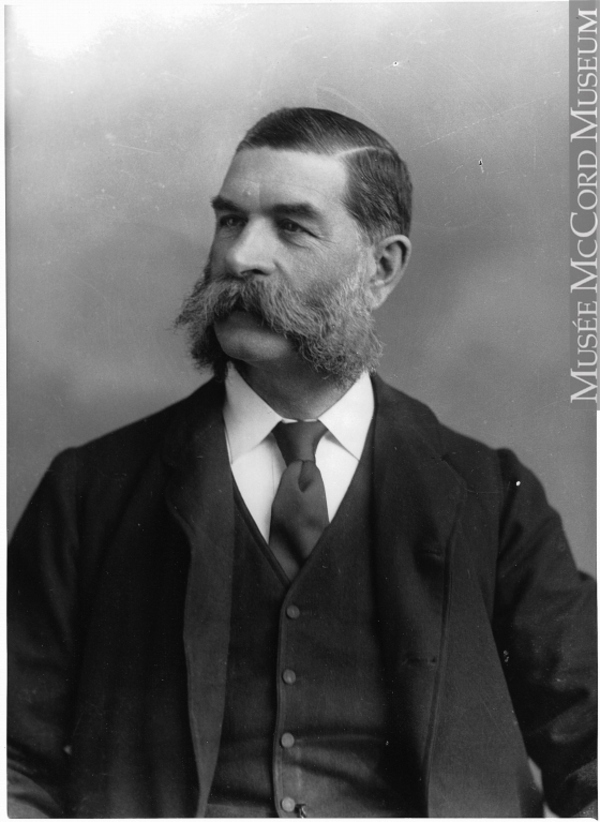

OGILVIE, WILLIAM WATSON, militia officer and businessman; b. 15 Feb. 1835 in Côte-Saint-Michel (Montreal), son of Alexander Ogilvie and Helen Watson; m. 15 June 1871 Helen Johnston, daughter of Joseph Johnston of Paisley, Scotland; d. 12 Jan. 1900 in Montreal.

William Watson Ogilvie was born into a large family, the tenth of eleven children. His father, Alexander, had emigrated to Lower Canada from Scotland with his family in 1800 and farmed near Châteauguay River, south of Montreal. In 1801, the Ogilvies set up a grist-mill at Jacques-Cartier, near Quebec. This enterprise marked the start of the family’s long and distinguished association with the Canadian milling business. Ten years later, Alexander joined with his uncle and his future father-in-law, John Watson, to erect a mill at Montreal, establishing the business he would eventually leave to three of his sons: Alexander Walker*, John, and William.

At a young age William was confided to the care of his uncle William Watson*, Montreal’s flour inspector. He attended the High School of Montreal and was apprenticed as an inspector under Watson’s supervision. Following his two elder brothers Alexander Walker and John, he joined the Montreal Cavalry in 1857. He assumed the command of the cavalry in 1866 and prepared to help defend Canada from a possible invasion by the Fenian faction that had assembled in New York State [see John O’Neill*]. He was awarded the Service Medal by the Department of Militia and Defence for his share in thwarting the Fenians’ efforts.

During the 1850s and 1860s a Montreal merchant with sufficient capital and a willingness to take a risk could become very wealthy. The city was quickly emerging as the commercial centre of Canada and the point from which wheat and flour were exported abroad. In Europe, political, economic, and technological changes proved advantageous for the Canadian grain trade. In 1854, during the Crimean War, Britain was cut off from the Russian grain market and demand for Canadian supplies increased dramatically. As well, the development of the roller-milling process in Hungary in the late 1830s, which had greatly improved the milling of wheat rich in proteins and gluten, eventually led to significant changes in the North American flour business.

In 1852 the Ogilvie mill (which in 1837 had been relocated from Montreal to the Lachine Canal) was managed by James Goudie, a brother-in-law of Alexander Ogilvie. That year Alexander Walker Ogilvie was made a partner and expanded the operation. Both Goudie and Alexander Sr retired by 1855, leaving the business in the hands of Alexander Walker and his brother John. The firm was renamed A. W. Ogilvie and Company. William joined his brothers as a partner in May 1860, an astute business move. In 1871, shortly after his marriage, he purchased a mansion on Simpson Street in Montreal’s fashionable Mount Royal district. Called Rosemount, it was “one of the finest residences in the city.”

During the period after confederation, the Ogilvies made two important business decisions which ensured their continued success. First, they capitalized on technological innovations in milling developed in Europe. In 1868 William, accompanied by his brother Alexander Walker, travelled to Hungary to inspect the latest milling process, which used steel reduction rolls for grinding instead of millstones. On their return the Hungarian system was adopted in their own mill to produce a superior grade of flour.

A second significant move by the Ogilvies was to expand westward as new areas of Ontario and the prairies were settled. In 1872 their first Ontario mill was built at Seaforth and two years later a second one was erected at Goderich with a daily production capacity of 500 barrels. By this time Alexander Walker had become involved in politics and other business activities. When he retired from active management of the milling company in 1874, William was made head of the firm’s Montreal office and John assumed control of the mills in Ontario.

The Ogilvies shipped their first load of wheat from Manitoba in 1877 and for the next decade dominated the grain trade of western Canada, which was experiencing an agricultural boom. Following their policy in Ontario of producing flour at the point where the grain was grown, they built a mill at Winnipeg in 1882. Regular shipments of flour from Manitoba commenced shortly after. Their entrance into the grain elevator business, however, caused controversy.

The Canadian Pacific Railway, in order to ensure that the shipment of grain eastward would be efficient and financially viable, promoted the construction of grain elevators. Its general manager in 1883, William Cornelius Van Horne*, offered any grain company free use of the land along the railway’s main line if it erected a steam-powered elevator of not less than 25,000 bushels capacity. The railway company promised, as well, that it would not allow grain to be loaded on to its cars from farmers’ wagons or flat warehouses (covered storage bins with no mechanical equipment) at points where elevators had been constructed. Since John and William Ogilvie had built at Gretna, in 1881, one of the first country grain elevators in the province of Manitoba, they were quick to take advantage of the CPR’s generous offer. As part of a special arrangement made with Van Horne in 1883, the milling company agreed to ship 25,000 sacks of flour from Port Arthur (Thunder Bay), Ont., via the CPR’s lake steamers, and in return it received a rebate on its freight rate payments. It has been estimated that by the end of 1884 this bonus amounted to approximately $50,000. By the following year the Ogilvies operated eight elevators in Manitoba and plans were under way for further construction.

Manitoba producers soon protested that the railway company and the Ogilvie Milling Company constituted a monopoly. Indeed, evidence exists (in the Van Horne letter-books) to suggest that in 1884–85 the Ogilvies’ country buyers did not always pay farmers a fair price for their grain. But as the western Canadian grain business expanded, more controls over the system were put into effect. In 1900 the first federal royal commission on the grain trade noted the problems in policing the country grain buyers, yet concluded there was no evidence to show “that any elevator owners [had] been consenting parties to any acts of extortion.” By that year, the Ogilvie Milling Company was operating 45 country elevators in Manitoba (approximately 10 per cent of the province’s total).

Success in the west resulted in expansion in the east. The company’s Royal Mill in Montreal was opened in 1886. It had a daily capacity of 2,100 barrels with an adjoining elevator capable of holding 200,000 bushels of wheat. One worker at the new mill recalled William Ogilvie in this way: “He was a fine figure of a man, tall, with a keen face and impressive sideburns, the very cut of a cavalry officer. He led his millers a merry life – always hiring, discharging and re-hiring them.” Ogilvie assumed total control of the company after his brother John died in 1888. By the turn of the century he had made the firm the largest milling company in the dominion with a worldwide reputation for producing high-quality flour.

As one of the leading merchants of Montreal, Ogilvie was an active member of the city’s business establishment. He was the president of the Montreal Board of Trade in 1893 and 1894, and a member of its council for six years. He was also a director of the Bank of Montreal, the Montreal Transportation Company, and the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. A generous philanthropist, he supported numerous charities and institutions across Canada including McGill University and the Winnipeg General Hospital. In politics, he was a member of the Conservative party. He campaigned for his brother Alexander Walker’s appointment to the Senate in 1881, noting in a letter to Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald the past loyalty of the Ogilvie family to the party. He made substantial contributions at election time and favoured Macdonald’s National Policy.

William Watson Ogilvie died in 1900 a very wealthy man, leaving his wife and their three sons and a daughter a substantial fortune. Total movables of domestic items, cattle, cash, and other possessions represented $1,431,401, including his home’s furniture and his collection of 118 water-colours evaluated altogether at $24,000; debts owed to him were $284,832. But he and his brothers should be remembered most for their pioneering work in the milling trade and for their willingness to take a risk in the Canadian west.

In 1902 the executors of Ogilvie’s estate sold the milling company and its 70 country elevators to a Canadian syndicate headed by Charles Rudolph Hosmer, a Montreal financier, and Frederick William Thompson, general manager of the Ogilvie Company’s western Canadian interests. Renamed Ogilvie Flour Mills Company Limited, the firm continued to grow and prosper through the boom years of western settlement and for decades thereafter. A new Royal Mill was built in 1941 in Montreal; it was ultramodern for its time, with a daily capacity of 15,000 bags of flour and feeds. In 1949 Gerber-Ogilvie Baby Foods Limited was formed to process cereals and strained food.

ANQ-M, CE1-125, 27 avril 1835, 15 janv. 1900; CN1-501, 15 juin 1900. Montreal Board of Trade Arch., Minute-books, general minute-book, 30 Jan. 1900: 384. NA, MG 26, A, 16, W. W. Ogilvie to J. A. Macdonald, 29 Oct. 1881; 136, Ogilvie to Macdonald, 5 Nov. 1890; 324, Ogilvie to Macdonald, 25 Oct. 1887; 354, Ogilvie to Macdonald, 23 Jan. 1879; MG 28, III 20, Van Horne letter-books, 3, Van Horne to Harder, 12, 16 Nov. 1883; 4, Van Horne to Ogilvie, 31 Jan. 1884; 5, Van Horne to Ogilvie, 2 April 1884; 9, Van Horne to Ogilvie, 10 Dec. 1884; 11, Van Horne to Egan, 29 March 1885, Van Horne to Ogilvie, 27 May 1885, Van Horne to Kerr, 8 Dec. 1885. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1900, nos.81–81a (report of the royal commission on the shipment and transportation of grain). Commercial (Winnipeg), 11 Feb. 1889. L’Événement, 13 janv. 1900. Gazette (Montreal), 13 Jan. 1900. Monetary Times, 19 Jan., 16 Feb., 13 April 1900. Nor’West Farmer and Manitoba Miller (Winnipeg), December 1883. Canadian biog. dict., 285–86. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Encyclopedia Canadiana, 8: 6. Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). Wallace, Macmillan dict. Atherton, Montreal, 3: 106–11. [J. A. Gemmill], The Ogilvies of Montreal, with a genealogical account of the descendants of their grandfather, Archibald Ogilvie (Montreal, 1904). D. R. McQ. Jackson, “The national fallacy and the wheat economy: nineteenth century origins of the western Canadian grain trade” (ma thesis, Univ. of Man., Winnipeg, 1982). A. [G.] Levine, The exchange: 100 years of trading grain in Winnipeg (Winnipeg, 1987). G. R. Stevens, Ogilvie in Canada, pioneer millers, 1801–1951 ([Montreal, 1952]). Tulchinsky, River barons. B. R. McCutcheon, “The birth of agrarianism in the Prairie west,” Prairie Forum (Regina), 1 (1976): 79–94.

Cite This Article

Allan Levine, “OGILVIE, WILLIAM WATSON,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 21, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ogilvie_william_watson_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ogilvie_william_watson_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Allan Levine |

| Title of Article: | OGILVIE, WILLIAM WATSON |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 21, 2025 |