As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Link

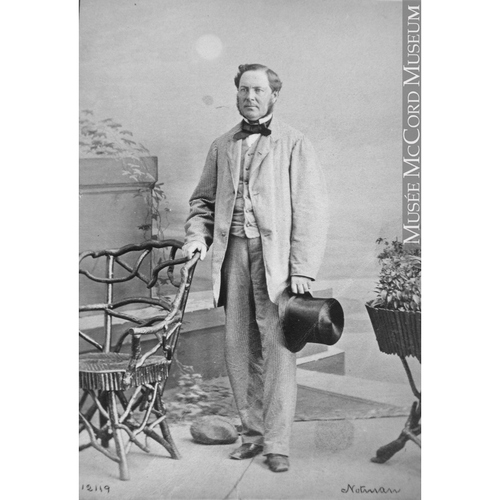

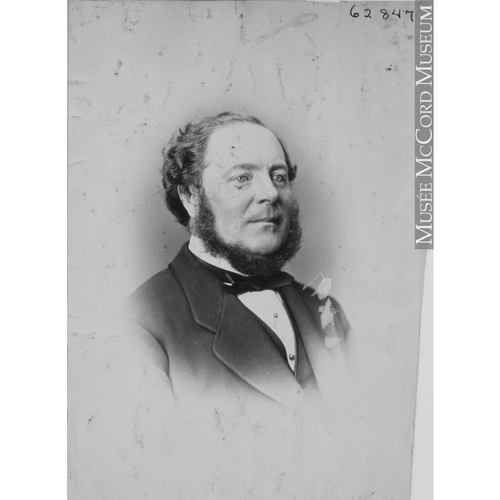

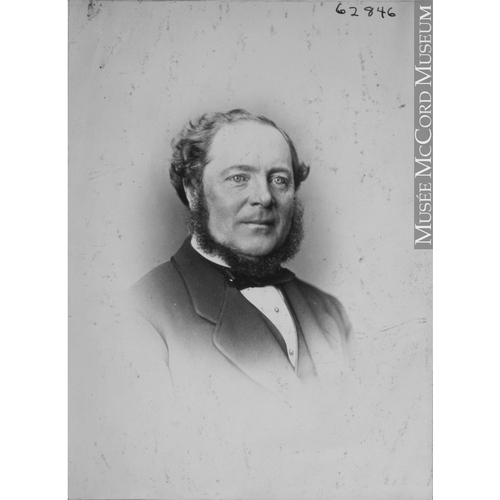

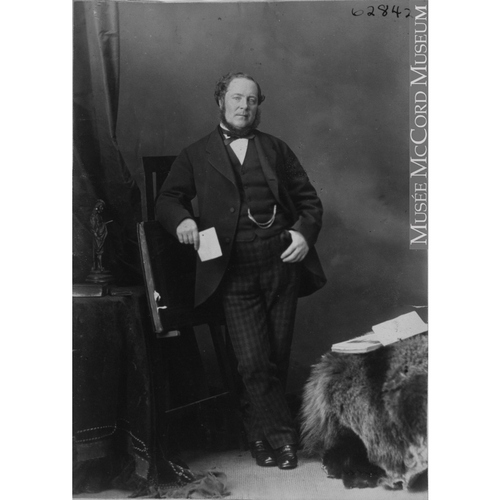

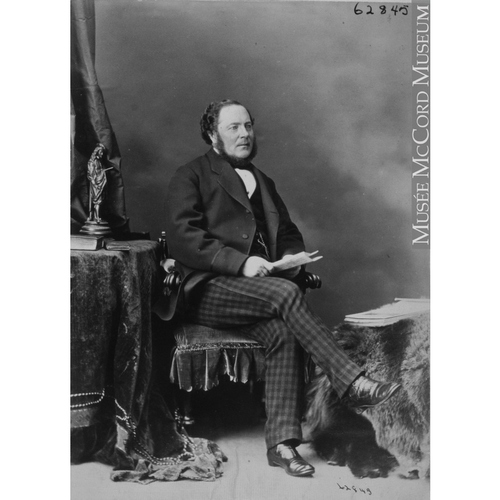

BUNTIN, ALEXANDER, businessman; b. 21 Oct. 1822 in Renton, Scotland, son of Alexander Bontine and Isabel McLeod; m. Isabella McLaren, and they had at least four daughters and one son; d. 24 March 1893 in Bath, England.

At the age of about 15 Alexander Buntin took ship for St John’s, Nfld, as an apprentice. Finding the sailor’s life not to his liking, he decided to try his luck at Quebec. There he went to work for McDonald and Logans, which had a stationery business at Quebec as well as a paper-mill in Portneuf. He learned the rudiments of business with the firm. Later he went to Montreal, where he is said to have worked for Robert Weir, a paper-goods wholesaler, and then for William Miller and Company, an agency of McDonald and Logans. In the fall of 1848 he founded Buntin and Company, a wholesale and retail firm selling paper and office supplies, in Hamilton, a city becoming the distribution centre for the north and west of Upper Canada. Buntin formed a partnership with his brother James on 1 May 1852 but later that year he returned to Montreal to work as a clerk for William Miller and Company.

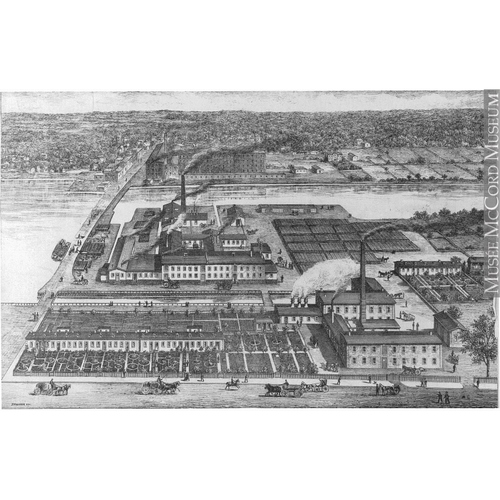

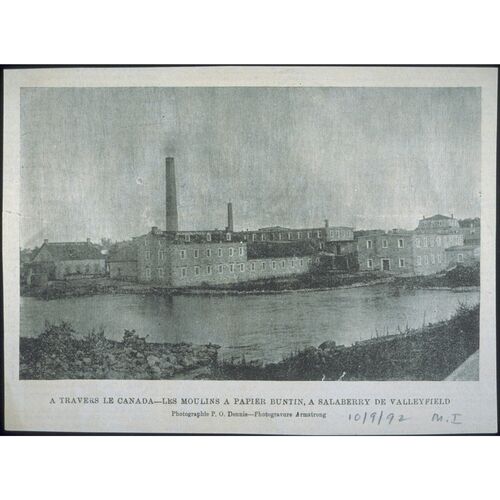

In 1854 the Paper Manufactory, in which Buntin would be involved, was built for William Miller at a place he named Valleyfield (Salaberry-de-Valleyfield), near the Beauharnois Canal. This ultramodern establishment, equipped with an 84-inch-wide Fourdrinier machine, began production in April; two years later it would employ 26 men and 45 women and its worth would be estimated at $48,000 or £12,000. However, apparently finding himself short of liquid assets, Miller sold his Montreal stationery business in 1854. According to historian George Carruthers, Miller, fearing bankruptcy, also transferred his shares in the plant to Buntin for a nominal sum, on the understanding that he would regain control of them later, on terms known only to the two men. Thus Buntin founded Alexander Buntin and Company, probably in the spring of 1854. Carruthers claims, without proof, that in 1856 Buntin refused to transfer the shares back to Miller, who withdrew from the business. Buntin then took his brother into partnership (he had sold him his share in their Hamilton enterprise the previous year); until about 1864 the Valleyfield plant went under the name of A. and J. Buntin. The two also opened Buntin, Brother and Company, a wholesale and retail paper-goods business in Toronto, in 1856. This expansion stemmed from the fact that the Valleyfield mill had markets in Lower Canada for only a third of its annual output, a total that year of 500 tonnes of paper.

In 1861 Alexander’s brother died unexpectedly, leaving him the sole owner of all the enterprises, which he had to reorganize. In Hamilton he went into partnership with George Boyd until 1865, and then with his nephew David Gillies, under the name of Buntin, Gillies and Company. In Toronto he was in business with George Boyd and John Young Reid from 1861 to 1878 and with Reid alone from 1878 to 1893 (the firm exists today as Buntin Reid Paper). But he himself remained the sole owner of the Valleyfield plant. To meet the growing demands of the domestic market, he improved the equipment in his mill. Between 1866 and 1869 he introduced a mechanical pulp process perfected by Heinrich Voelter, a German, from an invention by Friedrich Gottlob Keller which involved three machines: a “defibrer,” a refiner, and a sorter made of wire-gauze cylinders. Buntin had read about this process in a trade journal and had gone to Germany around 1865 to see how the machines worked. He ordered at least two “defibrers,” which were in operation at Valleyfield by 1869. The mill used debarked, foot-long logs of Manitoba maple eight to ten inches in diameter. It was said to be a first in North America. Other improvements followed. The plant eventually had three Fourdrinier machines varying in width from 60 to 84 inches, and devices turning out some 20,000 envelopes a day. Around 1879 it began to sell pulp in England. Until the mid 1880s the plant continued to be one of the most advanced in the paper industry. But in 1891 it was in decline after Buntin lost interest and chose to diversify his investments rather than modernize his equipment: at this time his fixed capital was evaluated at $120,000 and his assets at $150,000; he had 72 employees, including 22 women, on his payroll.

Buntin did not manage his paper business himself. In January 1857 he had entrusted the operation of the mill to John Crichton, an experienced paper maker, who was replaced in 1887 by George di Madeiros Loy, an accountant with the firm who had a thorough knowledge of chemistry. The skilled workers and employees at the management level were Presbyterian Scots. The factory operated day and night, six days a week. Unusually, because of a tradition established by the first manager, Hugh Wilson, no work was done on Sundays. Apparently there was never a strike.

Buntin invested the substantial income he derived from these enterprises in shipping companies. In 1864 he was one of the founders of the Beauharnois, Châteauguay, and Huntingdon Navigation Company, which served the ports between Cornwall, Upper Canada, and Montreal, and he apparently suffered heavy financial losses when it went bankrupt some five years later. In 1868 he invested in the Canada Shipping Company, better known as the Beaver Line, set up by a group of Montreal capitalists led by William Murray. The following year the Beaver Line had six steamships travelling between Montreal and Liverpool, England. It too went bankrupt, however, in 1895.

Buntin gradually made his way into the closed world of Montreal finance. He was part of the inner circle of the brothers Mathew Hamilton* and Andrew Frederick* Gault. In 1871 he and Mathew were involved in setting up the Sun Mutual Life Insurance Company of Montreal (later known as Sun Life); he was to be one of its major shareholders. Along with Mathew he also held a substantial interest in the Exchange Bank of Canada, founded in 1872. But his relations with the Gault brothers were sometimes stormy. In 1871 they manœuvred to have his election as vice-president of the insurance company declared invalid; in 1883, following the failure of the Exchange Bank of Canada – an unforeseen event that reportedly cost him about $260,000 – Buntin, through someone else, secured Mathew’s resignation as vice-president of the company. He is also said to have refused to help organize the Montreal Cotton Company because he distrusted the machinations of the Gault brothers.

Because of his involvements in the financial world Buntin had to spend more and more time away from his mill. In 1883 he brought one of his employees, Andrew Boyd, into partnership in his paper business, under the name of Buntin, Boyd and Company. Five years later Boyd founded his own firm and Buntin took his son, who was also named Alexander, as a partner, forming Alexander Buntin and Son, which then owned the mill and the paper business. His health was deteriorating. On the advice of his doctor he went for a rest-cure to Bath, England, where he died on 24 March 1893. His will stipulated that the executors – his wife, George di Madeiros Loy, and George Hyde – were to keep the Valleyfield mill in operation for seven years. And indeed, the mill, bought by the Montreal Cotton Company, would produce its last sheet of paper on 23 July 1900, before being torn down.

Alexander Buntin’s career illustrates the exceptional role of the Scots in building the Canadian economy, and the way in which clan relationships undergirded their business successes. He himself built up a reputation as a bold entrepreneur, who was extremely proud of his personal success. Adam Brown of Hamilton recounts in his memoirs that Buntin, on being told he was “as rich as Croesus,” replied: “I don’t know who Croesus is, but I will put up two dollars to his one.”

[We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mrs Gladys Barbara Pollack and two colleagues at the DCB/DBC, Elizabeth Hulse and Robert Lochiel Fraser, in the preparation of this biography. j.h. and m.p.]

GRO (Edinburgh), Renton, reg. of births and baptisms, 21 Oct. 1822. HPL, Arch. file, Brown-Hendrie papers, reminiscences of Adam Brown. “Documents inédits: the manufactures of Montreal,” RHAF, 6 (1952–53): 139. Gazette (Montreal), 25 March 1893. Hamilton Evening Times (Hamilton, Ont.), 22 Oct. 1866. Hamilton Gazette, 30 Oct. 1848. Hamilton Spectator, 12 July 1851, 25 June 1855, 21 June 1864, 16 May 1884, 24 July 1893. Hamilton Times, 24 March 1893. Montreal Daily Witness, 25 Aug. 1900. Dict. of Toronto printers (Hulse). Lovell’s historic report of census of Montreal (Montreal, [1891]). Montreal directory, 1842–93. Quebec directory, 1847–53. George Carruthers, Paper-making (Toronto, 1947). Jean Hamelin et Yves Roby, Histoire économique du Québec, 1851–1896 (Montréal, 1971). Dard Hunter, Papermaking, the history and technique of an ancient craft (abridged ed., New York, 1978). Augustin Leduc, Beauharnois, paroisse Saint-Clément, 1819–1919; histoire religieuse, histoire civile; fêtes du centenaire (Ottawa, 1920). Esdras Minville, La forêt (Montreal, 1944). Joseph Schull, The century of the Sun; the first hundred years of Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada (Toronto, 1971). “Buntin, Gillies marks centenary in business here,” Hamilton Spectator, 14 Dec. 1948. “Firm in business here since 1848,” Hamilton Herald, 29 June 1927. “Gillies,” Hamilton Spectator, 26 June 1926.

Cite This Article

Jean Hamelin and Michel Paquin, “BUNTIN, ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buntin_alexander_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/buntin_alexander_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Hamelin and Michel Paquin |

| Title of Article: | BUNTIN, ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |