Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

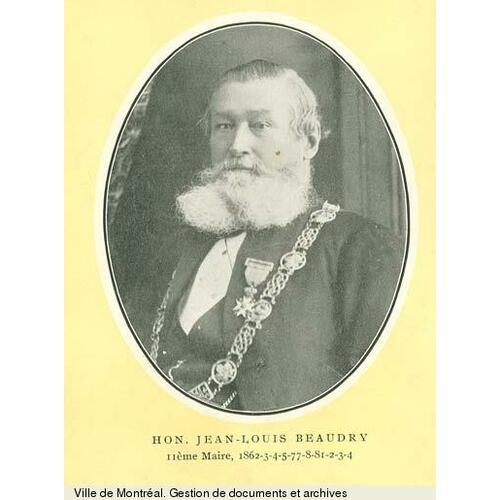

BEAUDRY, JEAN-LOUIS, entrepreneur and politician; b. 27 March 1809 at Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Lower Canada, one of five sons of Prudent Beaudry and Marie-Anne Bogennes; m. 18 May 1835 in Montreal, Lower Canada, Thérèse, daughter of merchant Joseph Vallée, and they had one son and four daughters; d. 25 June 1886 at Montreal.

In 1823 Jean-Louis Beaudry, “a pushing, determined, industrious lad,” left the family farm in Terrebonne County for the commercial world of nearby Montreal. There he quickly found work as a clerk in a dry goods store on Rue Saint-Paul, and he apparently remained in this position until 1826, perhaps acquiring in the mean time a working knowledge of English. He then moved to the new settlement of Isthmus (Newboro) in Leeds County, Upper Canada, where for the next four years he served as a storekeeper for Messrs Baraille and Company, a Montreal-based firm supplying goods to the labourers constructing the Rideau Canal. Upon his return to Montreal, Beaudry acquired a position with an English mercantile house from which he was subsequently dismissed in 1832 because of his activities supporting the Patriote party during the violent by-election in April and May for the assembly seat of Montreal West [see Daniel Tracey*]. Probably because of his considerable expertise in merchandising, Beaudry quickly found employment with yet another English merchant on Rue Saint-Paul, William Douglass.

In 1834 Beaudry and his younger brother Jean-Baptiste opened a dry goods store on Rue Notre-Dame. Through Jean-Louis’s ceaseless work and considerable ability the store, featuring damaged goods and stock from bankruptcies at bargain prices, soon became an immense success. Although Beaudry handled the purchasing end of the business, making a dozen trips to Europe over the next 15 years, he also contributed a keen, early appreciation of popular advertising. The huge shutters of the building were painted in gaudy red, white, and blue stripes, quickly acquiring for the business a local notoriety as the “store with the striped shutters.”

Beaudry was also making a name for himself in politics. His sympathies had been evident as early as 1827 when he signed the petition carried to England by John Neilson*, Denis-Benjamin Viger*, and Augustin Cuvillier* to express the opposition of the Patriote party to the proposed union of the Canadas. He subsequently identified himself readily with the aspirations of the party, in particular with the policies of Wolfred Nelson*, Cyrille-Hector-Octave Côté*, and Ludger Duvernay*. Although still relatively young and unsuited by his lack of education to assume a significant leadership role, Beaudry possessed the necessary tenacity and penchant for physical action to throw himself “body and soul” into the movement. By the late summer of 1837, when the situation had deteriorated to the point where paramilitary associations were being formed in the city, Beaudry had acquired sufficient popularity to be chosen a vice-president of the political wing of the Fils de la Liberté.

His prominence, however limited, had its drawbacks. Apparently fearing arrest following the street clash on 6 November between the Fils de la Liberté and the Doric Club, Beaudry left Montreal for the countryside. Whether he remained in the province long enough to participate in the first heady episodes of rebellion at Saint-Denis and Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu later that month is unknown. By the end of November, however, he along with other Patriotes was safely in Vermont. As the Patriotes’ “agent in Montpelier,” Beaudry toured sympathetic American centres raising money and munitions for Robert Nelson* who was planning an invasion of Lower Canada. Beaudry’s efforts, however, were soon hampered as a result of strict enforcement by American authorities of a neutrality act passed in March 1838. Some time following the general amnesty proclaimed by Lord Durham [Lambton*] in June, Beaudry, a “voluntary exile,” not having been explicitly named as a leader of the rebellion and thereby not subject to arrest, returned to Montreal and quietly resumed his business career.

The rebellions left their mark upon Beaudry. Although a militant Patriote, he had never been particularly close to the wing of the movement led by Viger and Louis-Joseph Papineau*, and following the union of the Canadas in 1841 he easily accepted the leadership of Louis-Hippolyte La Fontaine* and Robert Baldwin* and their demand for responsible government. Beaudry’s support, however, was not unwavering; in 1849, perhaps as a result of his business concerns, he signed the Annexation Manifesto. He remained a fixture in Montreal nationalist circles, taking part in virtually every patriotic movement that arose. Characteristically, he was instrumental, along with other local notables, in founding in June 1843 the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal. His conventional response to the politics and nationalism of the period was reflected as well in his attitude towards religion: he became, and remained, strongly identified with the Ultramontanes in the Roman Catholic Church in the province.

Beaudry was not a conventional businessman. By 1837–38 he had already realized a “respectable fortune” from his retail trade and, although he continued to be successful in this field, he also began speculating in land, becoming “one of the largest real estate owners in the city.” More interestingly, however, Beaudry was also one of the most active of a group of French Canadians who participated in the burgeoning field of joint-stock ventures. Although he was involved in many such concerns during his career, including utilities, insurance companies, railways, and banks, his participation from 1853 to 1856 on the board of directors of the unsuccessful Montreal and Bytown Railway as “perhaps the most prominent of the French Canadian businessmen involved,” and his founding of the Banque Jacques-Cartier in 1861 are the most important.

Beaudry’s position in the city’s business circles led to his appointment in the late 1840s as a warden of Trinity House, Montreal, the body whose main function was the regulation of navigation into the port. He retained this post until Trinity House was abolished in 1873 and its duties assumed by the Montreal Harbour Commission. Subsequently named a commissioner, he served until shortly before his death.

If Beaudry’s business abilities and his nationalism won him general respect and a growing leadership role in the Montreal French Canadian community, his personality attracted considerable hostility. All sources tend to agree that he showed great energy, courage, and determination: that he possessed “backbone.” A wide segment of the press, however, was quick to elaborate upon his shortcomings. He was stubborn to an extreme, hot-tempered, rude, and brutally candid. Although his personal honesty was never seriously questioned, there was some unflattering reference to his sharp business practices. An article in L’Opinion publique noted: “Beaudry is not well read. . . . This is not to say that he has no education. . . . But of all the books in the world, the one he is most fond of . . . is his cashbook.” His later career in municipal politics would heighten public reaction, both positive and negative, but much of the city’s English-language press exhibited strong animosity, a reaction based to a large extent on his personality and style rather than his policies. After his death one newspaper would refer casually to his four illegitimate children.

In 1854 and again in 1857 Beaudry presented himself in the three-member riding of Montreal as the Liberal-Conservative candidate for the assembly and on each occasion was easily defeated by his opponents. Rebuffed on the provincial level, he soon turned to Montreal municipal politics, where his involvement in numerous associations and his eminent business reputation left him with few rivals. It was also an area in which the city’s English-speaking population tended to play a less significant role than their numbers warranted.

In June 1860, upon the resignation of the councillor for St James Ward, Beaudry was returned to the city council of Montreal during a by-election. He was returned in St James by acclamation during the municipal elections of February 1861 and, two weeks later, elected an alderman by his fellow councillors. The following year Beaudry contested and won the mayoralty from the incumbent Charles-Séraphin Rodier* by 332 votes. His victory was decisive and it had been achieved against the determined opposition of the Montreal English-language press whose motivation was dislike of Beaudry rather than any particular fondness for Rodier. The Conservative Pilot led the assault: “better half a century of Rodier than half an hour of Beaudry.” The mayoralty would offer him “almost unlimited opportunity for nice little money making transactions.” Its pleas were in vain. While the “British portion” of the inhabitants absented themselves from the polls, Beaudry carried the French Canadian east-end suburbs and the west-end Irish vote, “which was almost unanimously thrown in his favour.”

In 1863 Beaudry retained the mayoralty when his only opponent, Benjamin Holmes*, retired from the race, and he was again acclaimed in 1864. In 1865 he handily defeated an Irish Catholic candidate but the following year, perhaps sensing growing opposition to yet another year in office and seeing a strong candidate in Henry Starnes*, a former mayor, Beaudry took the Gazette’s advice: “If Mr. Beaudry . . . were to take a few years of rest from his public labours, we are sure he would meet with less strenuous and less effective opposition in another contest . . . .” Beaudry declined to run.

The position of mayor in 19th-century Montreal conferred prestige but little power upon the officeholder. Under the city charter the mayor acted as convenor, in effect speaker of the council. In 1852 the charter had been amended to allow the direct annual election of the mayor, thus removing from the council the right to select its own presiding officer. This amendment served to discourage capable individuals from going through the trouble and expense of annual election to a largely powerless position.

Beaudry was not deterred by these conditions. He compensated for the lack of direct powers to initiate or to veto bills by bullying or obstructing the council through his sheer force of character. As an inveterate conservative he had ample opportunity during his term of office in the 1860s to provide what a “Scottish Protestant” had described in his letter to the Montreal Gazette as “factious opposition to many of our most valuable public improvements.” Furthermore, Beaudry possessed sufficient demagogic qualities to be attracted rather than repelled by the burden of annual elections. And the prestige and limelight surrounding the position were immensely attractive to a businessman who had heretofore existed on the fringe of political and public life.

Following confederation in 1867 he was appointed a provincial legislative councillor for Alma division, a position in which all commentators agree he served energetically and ably until his death to further the interests of Montreal. In 1868, after the lapse of only two years, he again presented himself for mayor, this time in opposition to the widely esteemed Liberal businessman, William Workman*. Beaudry accused Workman of being an accomplished swindler of the public purse. He also introduced religious and national antipathies into the campaign as well as unsubtle east end versus west end appeals. He badly miscalculated in his clumsy electioneering tactics against his genuinely popular Protestant opponent. Beaudry received fewer than 1,900 of the 5,000 votes cast. The contest had demolished his fragile reputation. He was now widely viewed as a man consumed by unrestrained political ambition who, according to Workman, had used “the most bitter, most violent, most unjust, and most unscrupulous means of obtaining the end at any cost.” Lingering resentment contributed substantially to his absence from municipal office during the next ten years.

By the late 1870s, however, political animosities had sufficiently subsided to allow Beaudry to regain the mayoralty. In 1877 he won a crushing victory over Ferdinand David, and the following year was returned by acclamation. His second mayoralty was marked by much the same conservatism and obstructionism as the first. His response, however, to the 12 July disturbances in 1877 and 1878 is significant. In 1877 members of Orange order who had attended a church service were attacked by a Catholic mob and during the ensuing mêlée Thomas Hackett, an Orangeman, was shot and killed. Beaudry bore the brunt of criticism in the city’s English-language press for not having used the police to control the crowd. In 1878 he ignored the troops that had been called up to quell the expected riot and instead employed special constables to arrest the Orange leaders as they emerged from their hall for their customary march. Although the Gazette regretted his interference with civil liberties, it and the rest of the city’s English-language press generally were grudgingly restrained in the light of Beaudry’s successful defusing of an explosive situation.

His handling of the Orange crisis won him considerable support among the French Canadian and Irish Catholics of the city, but Beaudry was defeated in the mayoral election of March 1879. Sévère Rivard, his opponent, had nationalist credentials also but, unlike Beaudry, he was a resident of the city’s largely French-speaking east end and he was eminently acceptable as a candidate to the English-speaking west-end voters. Furthermore, Beaudry’s business reputation had recently suffered from the financial troubles of his Banque Jacques-Cartier and he had not been able to gain re-election to its board of directors. All these factors contributed to his defeat.

Within two years, however, Beaudry bounced back, wedging himself firmly once more into the mayor’s chair, this time for four consecutive terms from 1881 to 1885, defeating popular municipal politicians Horatio Admiral Nelson, John Layton Leprohon, and Henry Bulmer by respectable margins. Beaudry’s successes resulted partially from his playing his nationalistic credentials against the confidence placed by his English-speaking opponents in the tradition of alternating English and French mayors for the city. He was also assisted by the annexation in 1883 of the faubourg of Hochelaga, which gave Montreal a comfortable majority of French Canadian electors. More interestingly, a growing body of Rouges at city hall and their popular newspapers, particularly Honoré Beaugrand*’s La Patrie, had since 1883 swung their support to Beaudry, the Conservative.

During the civic election of 1885, however, the intelligent, highly charismatic, and frankly brazen Beaugrand himself decided to run. Presented with the choice of a Rouge or a Conservative candidate and seeing the machinations of Liberal Senator Joseph-Rosaire Thibaudeau behind an attempt by the Rouges to take over the city council, the Conservative Gazette swallowed years of frantic hostility and threw its support behind Beaudry. It and La Minerve, however, stood virtually alone in their support of the incumbent. Beaudry’s demagoguery, his hostility to a muchneeded programme of public sanitation, his notorious quarrels with council, and his general obstructionism had made him a nuisance, more and more irrelevant to the realities of an increasingly complex municipal administration. Against a lively, competent reformer and nationalist like Beaugrand, he stood little chance. Beaugrand emerged victorious by more than 400 votes.

Beaudry’s municipal career was over. About a year later, on 15 June 1886, he took ill while attending the Legislative Council at Quebec. He was able to return to Montreal but ten days later he died of a paralytic stroke. He had been a prosperous businessman, leaving an estate valued at approximately $500,000, and certainly a successful Montreal mayoral candidate. His nationalism had interested him in politics in the 1820s and it remained an important force until the end. On 23 Nov. 1885 Beaudry delivered his last public address to the great crowd assembled on the Champ de Mars to protest the hanging of the Métis leader Louis Riel. In recalling the event L’Étendard wrote: “That day he was one of the speakers most applauded and, while a conservative, he showed that, standing firmly for the national cause, he was first and foremost a French Canadian patriot.”

AC, Montréal, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Darne de Montréal, 28 juin 1886. PAC, MG 24, B2. Sylvain Forêt, “L’honorable J.-L. Beaudry,” L’Opinion publique, 22 mars 1883. L’Étendard, 26 juin 1886. Gazette (Montreal), 8, 9 June 1860; 1, 12 March 1861; 24 Feb., 1 March 1865; 26 Jan., 7 Feb. 1866; 21 Jan., 11 Feb., 2 March 1868; 17 July 1878; 28 Feb. 1879; 21 Jan., 12 Feb., 3 March 1885; 26 June 1886. La Minerve, 18 mai 1835, 5 nov. 1867, 10 janv. 1885, 26 juin 1886. Montreal Daily Star, 25, 28 June 1886. Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, 26 June 1886. La Patrie, 26 févr. 1883; 27 janv., 13 févr. 1885; 26 juin 1886. Pilot (Montreal), 22, 27 Feb., 1 March 1862. Canadian biog. dict., II: 78–79. Fauteux, Patriotes. G. Turcotte, Le Conseil législatif de Québec. David, Patriotes. Histoire de la corporation de la cité de Montréal depuis son origine jusqu’à nos jours . . . , J.-C. Lamothe et al., édit. (Montréal, 1903). Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, II–III. Tulchinsky, River barons. R. M. Breckinridge, “The Canadian banking system, 1817–1890,” Canadian Banker, 2 (1894–95): 443. Léon Trépanier, “Figures de maires,” Cahiers des Dix, 20 (1955): 149–77.

Cite This Article

Lorne Ste. Croix, “BEAUDRY, JEAN-LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/beaudry_jean_louis_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/beaudry_jean_louis_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lorne Ste. Croix |

| Title of Article: | BEAUDRY, JEAN-LOUIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |