As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

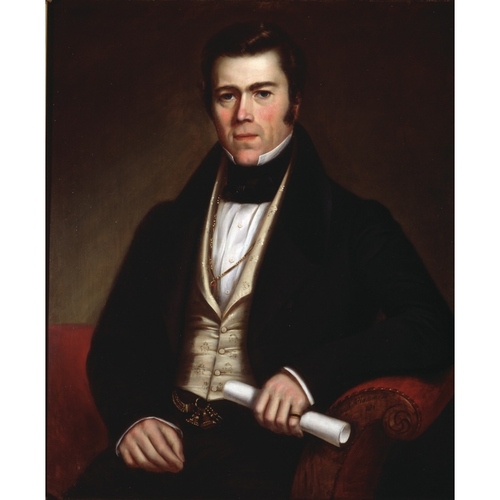

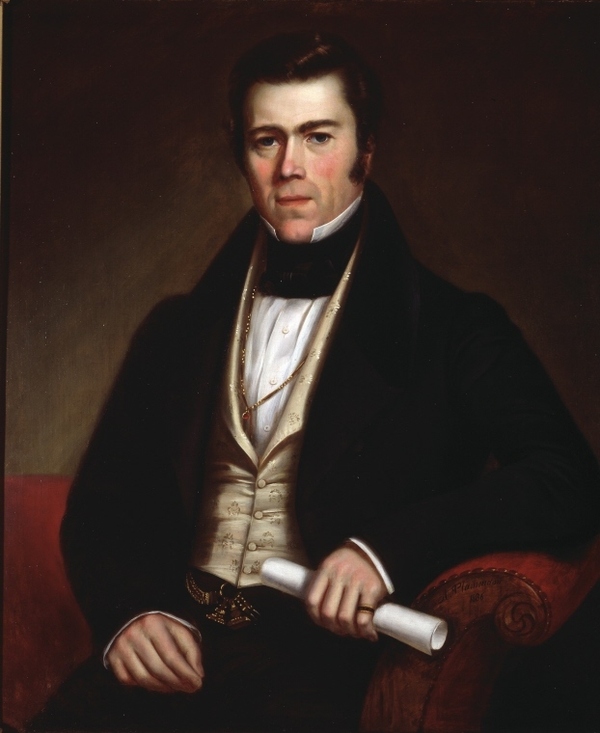

REDPATH, JOHN, contractor and industrialist; b. 1796 at Earlston, Berwickshire, Scotland; d. 5 March 1869 at Montreal, Que.

Of John Redpath’s life in Scotland before he left at the age of 20, we know only that he trained as a stone mason. In the early 1820s he emerged as a major building contractor in Montreal, supplying the stone for the new Notre-Dame Church and the Lachine Canal in partnership with Thomas McKay*. The canal was one of the most important public works of the early 19th century in Lower Canada and in building its locks Redpath gained a sound reputation. In 1827 and 1828 McKay and Redpath were engaged in building the locks at Jones Falls on the Rideau Canal, “the most extensive engineering undertaking at any one location along the Canal.” Redpath then seems to have returned to Montreal, although until 1831 he apparently retained an interest in a partnership with major contractors on the canal including McKay, Thomas Phillips, and Andrew White*.

It is not clear what business Redpath pursued after he returned to Montreal. He was already well-to-do and moved rapidly to the highest level of the Montreal business community. In 1833 he was elected to the board of directors of the Bank of Montreal, the city’s leading financial institution; until his death he was a director, after 1860 a vice-president, and a large shareholder. But like most of his wealthy colleagues Redpath put money into several enterprises of Montreal’s burgeoning economy of the 1840s, 50s and 60s. An investor in the Montreal Fire Assurance Company and the Montreal Telegraph Company, and a director of both, he also invested substantial sums in Canadian mining ventures – some in the Eastern Townships – including the Belvedere Mining and Smelting, Bear Creek Coal, Rockland Slate, Melbourne Slate, and Capel Copper companies. In addition, he owned shares in a copper smelter, a large share of the Montreal Investment Association, and much of the most desirable mountainside property in Montreal, and he had investments in shipping, the Montreal Towboat Company and the Richelieu Company [see Jacques-Félix Sincennes*]. He was also a promoter of the Canada Marine Insurance Company, the Metropolitan Fire Insurance Company, and the Canada Peat Fuel Company.

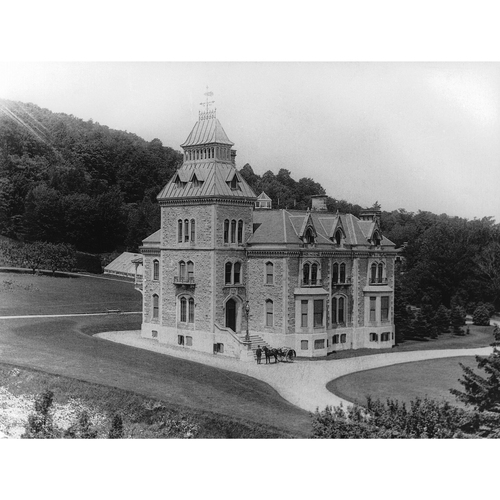

Despite these many financial interests and substantial wealth, Redpath would not have stood out among many equals in Montreal had it not been for his decision in 1854 to begin construction of the first sugar refinery in the Province of Canada. His was one of the largest establishments among more than 20 new plants in the recently opened industrial belt along the Lachine Canal. Redpath had started several years earlier to purchase land along the canal from the Sulpicians, the provincial government having not long before authorized the use of the canal’s water for industrial purposes. His seven-storey factory, whose towering smokestack became one of the city’s landmarks, represented an immense investment for Redpath, the sole owner. He put £40,000 into land, buildings, and machinery, and disposed of alike amount in working capital. Within a year, he had more than 100 employees and was producing 3,000 barrels of refined sugar per month for the Canadian market. His plant depended entirely on supplies of cane sugar imported from the West Indies, much of it in his own ships, the Helen Drummond and Grace Redpath, named after his daughters. By 1862 he was importing about 7,000 tons of raw sugar annually. Under the protection of favourable tariffs conveniently established by the Canadian government in 1855 – the year Redpath’s factory opened – the business prospered. By the mid 1860s another sugar refinery had been established in Montreal to compete with Redpath’s. In 1859 Redpath had brought his eldest son, Peter, and his son-in-law, George Alexander Drummond*, a young Scottish engineer, into the firm and made plans to retire gradually as more of his sons came of age, perhaps to enjoy his new country house, Terrace Bank, built on one of his Mount Royal properties overlooking the city where his substantial fortune had been founded.

Redpath had served a brief and undistinguished term as a member of Montreal’s city council from 1840 to 1843, but he had provided the province with other useful services. During the late 1830s he was a member of the Lachine Canal commission. In 1839 he was appointed to the newly created provincial Board of Works, resigning on 24 April 1840, and in 1845 he served on the commission of inquiry into the management of the Board of Works along with William Cayley*, Frédéric-Auguste Quesnel, George Sherwood, and Moses Judah Hayes [see Hamilton Hartley Killaly*].

Redpath was president in 1849 of the Montreal Annexation Association, which enjoyed broad, yet brief support from many of the city’s prominent businessmen. Requests for assistance from other annexationists, including Hugh Bowlby Willson*, editor of Toronto’s Independent, were forwarded to Redpath. There is a strong possibility that as an aspiring industrialist, who would have been concerned about markets for manufactured goods, Redpath was in part responsible for the emphasis in the association’s manifesto on the supposed advantages for Canadian manufacturers in union with the United States. His concern was perhaps reflected in his announcement to the annexationists in October 1849 that thousands of skilled Canadian artisans were moving to the United States. With the rapid decline of annexationism in Montreal in 1850, Redpath turned his interest in public welfare onto surer paths.

He had always been a charitable man in the best Christian tradition. He supported established institutions such as the Montreal General Hospital, the Montreal Presbyterian College, and the mechanics’ institute, all of which he served as a director, but he also, at the head of a small group, sought government assistance to fight Montreal’s white slavery traffic and, working through the local Magdalene Asylum, to redeem “unfortunate females, many of whom are poor immigrants who have been decoyed into the abodes of infamy and shame which abound in this city.” He also secured support for an insane asylum from the government, and helped establish the Protestant House of Industry and Refuge. A devout Free Church Presbyterian, Redpath was a founder of the Presbyterian Foreign Missions, the Labrador Mission, the Sabbath Observance Society, and the French Canadian Missionary Society; to the latter he left a substantial legacy.

Redpath had ten children by his first wife, Janet McPhee, whom he married in 1818. Following her death in 1834 he married Jane Drummond, and they had seven children. Only two of his sons, Peter and John James, appear to have joined the refinery. One of Redpath’s daughters married John Dougall*, editor of the Montreal Witness, another Henry Taylor Bovey, a well-known McGill University professor, and another George Alexander Drummond, who became the principal figure in the refinery and a prominent Montreal businessman.

Canada and Dominion Sugar Company Ltd. Archives (Montreal), Ledger, John Redpath and Son, p.44; Deeds files, 31 Dec. 1866. PAC, RG 4, C1, 121, no.259; 268, no.3063; RG 7, G20, 83–84, no.9558; RG 8, I (C series), 43, pp.181, 196–200; 45, pp.24–25; 221, pp.221–22; RG 11, ser.1, 24; RG 42, I, 175, pp.43–44, 47, 62. Private archives, Mr Quinton Bovey (Montreal), will of John Redpath (photocopy). “The annexation movement, 1849–50,” ed. A. G. Penny, CHR, V (1924), 236–62. Can., Prov. of, Statutes, 1841, c.98; 1859, c.115; 1864, c.98. Elgin-Grey papers (Doughty), IV, 1491. D. H. MacVicar, In memoriam; a sermon, preached in the Canada Presbyterian Church, Côté Street, Montreal, on Sabbath, March 14th, 1869, on the occasion of the death of John Redpath, esq., Terrace Bank (Montreal, 1869). Pilot and Evening Journal of Commerce (Montreal), 19 March 1844. Select documents in Canadian economic history, ed. H. A. Innis and A. R. M. Lower (2v., Toronto, 1929–33), II, 613–14. Borthwick, History and biographical gazetteer, 130. L. J. Burpee, The Oxford encyclopaedia of Canadian history (Toronto and London, 1926), 532. C. E. Goad, Atlas of the city of Montreal . . . (2nd ed., 2v., Montreal, 1890), I, xix, xxi. Montreal directory, 1841–53. C. D. Allin and G. M. Jones, Annexation, preferential trade and reciprocity; an outline of the Canadian annexation movement of 1849–50, with special reference to the questions of preferential trade and reciprocity (Toronto and London, [1912]), 136. Campbell, History of Scotch Presbyterian Church, 388. Denison, Canada’s first bank, II, 421. Hist. de la corporation de la cité de Montréal (Lamothe et al.), 204. R. [F.] Legget, Rideau waterway (Toronto, 1955), 106, 114, 116–18, 166–67, 220. O. J. McDiarmid, Commercial policy in the Canadian economy (Cambridge, Mass., 1946), 73. Montreal in 1856; a sketch prepared for the celebration of the opening of the Grand Trunk Railway of Canada (Montreal, 1856), 39–45. Redpath centennial, one hundred years of progress, 1854–1954 (Montreal, 1954). Franklin Toker, The church of Notre-Dame in Montreal; an architectural history (Montreal and London, Ont., 1970), 43–44. G. J. J. Tulchinsky, “Studies of businessmen in the development of transportation and industry in Montreal, 1837–1853” (unpublished phd thesis, University of Toronto, 1971), 425–29.

Cite This Article

Gerald Tulchinsky, “REDPATH, JOHN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/redpath_john_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/redpath_john_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Gerald Tulchinsky |

| Title of Article: | REDPATH, JOHN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | March 28, 2025 |