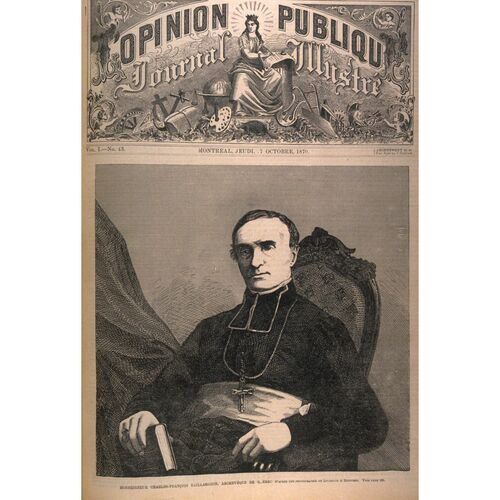

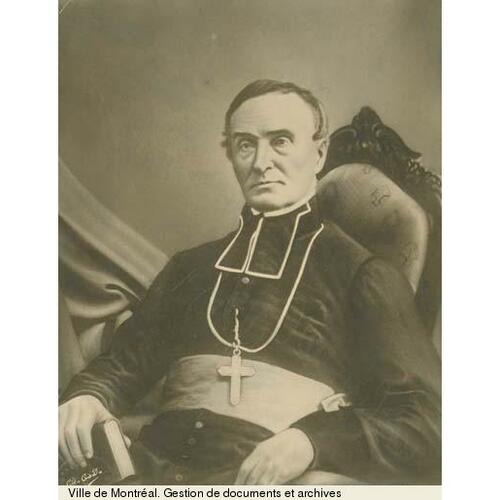

BAILLARGEON, CHARLES-FRANÇOIS, Roman Catholic priest, archbishop of Quebec; b. 26 April 1798 on Île aux Grues, Lower Canada (although his parents lived on Île aux Oies), son of François Baillargeon, a farmer, and Marie-Louise Langlois, dit Saint-Jean; d. 13 Oct. 1870 at Quebec.

Young Charles-François studied under Pierre Viau, the parish priest of Cap-Saint-Ignace, then in 1813 entered the Collège de Saint-Pierre-de-la-Rivière-du-Sud (Saint-Pierre-Montmagny), and the following year went to the Collège de Nicolet. His choice of the priesthood was confirmed during four years of theology at Quebec, where he taught at the college of Saint-Roch parish and then at the seminary. He was ordained priest on 1 June 1822, and appointed chaplain of the church of Saint-Roch and director of the college. This double responsibility affected his already delicate health, but after a rest cure at Saint-François, on Île d’Orléans, in 1826 he recovered his strength. The following year he became parish priest of Château-Richer, serving also L’Ange-Gardien. Four years later, in 1831, Bishop Bernard-Claude Panet* appointed him to the cathedral as a parish priest.

This appointment occurred when some members of the seminary had been planning to have the Quebec parish of Notre-Dame served by an association of priests. The experience of living and working together that had been tested over time at the seminary and among the Sulpicians of Montreal was to be the model. A group of 18 priests in the city, backed by the churchwardens and parishioners, favoured this undertaking, which would provide permanent confessors, a large number of preachers, and pastoral services based on a better knowledge of the parishioners. Bishop Panet was well disposed towards the plan, but foresaw numerous difficulties, in particular the opposition of his Coadjutor Bishop Joseph Signay*. In 1832 Bishop Signay became administrator of the diocese and had to come to a decision, as the plan had reappeared with the arrival of the new parish priest, Baillargeon. Indeed, the latter was prepared to set up the Société de la cure de Québec, which would enjoy the irremovability until then accorded only to the parish priest. After consulting Bishop Jean-Jacques Lartigue*, assistant to the bishop of Quebec at Montreal, Bishop Signay did not consider he had the right to make such a change. Baillargeon attributed this setback primarily to “the stubbornness of our dear bishop.”

The parish of Quebec imposed a heavy burden on its incumbent: about 900 baptisms and as many burials took place annually between 1831 and 1835; in 1834 there were 10,291 French and 6,270 English speaking Roman Catholics to be ministered to in a population of 23,343 persons. The tragic cholera years of 1832, 1834, and 1849 taxed Baillargeon’s missionary fervour to the full. Night and day he tended large numbers of dying persons at home or in hospitals. He took care of destitute families particularly among recent immigrants. He found homes for many orphans at Rivière-Ouelle, Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, L’Islet, and elsewhere. At the time of the disastrous fire in the district of Saint-Roch in 1845, his practical good sense and energy were of great help.

In these years Baillargeon was completing a project of Bishop Joseph-Octave Plessis*. This project, a French translation of the New Testament, was deemed important because the circulation of numerous Protestant versions encouraged unreliable interpretations. Bishop Lartigue had made a start but had never received the permission from Rome he believed necessary. In 1842 Baillargeon decided to proceed without bothering about the possible agreement of Rome. “Why such authorizations?” he wrote. “We assume a prohibitory law which I am sure does not exist.” For 15 months he worked at the project, four and a half hours a day. He wanted to produce a work accessible to all, but at the same time aimed at a faithful and exact translation of the Vulgate. He believed he was closer to the original than Louis de Carrières, Henri-François de Vence, Isaac Lemaistre de Sacy, Denis Amelote, Antoine-Eugène de Genoude, Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, and François de Ligny. In the 1,469 notes he refuted the Protestants’ objections by literal, moral, and dogmatic explanations. He insisted, however, that Bishop Signay should assume sole responsibility for the publication: it was for him “to feed the sheep on the Word.” Baillargeon’s work appeared in 1846, was recommended by all bishops in 1850, and was still in print in 1861. The author himself proposed that it be bought for all private and public libraries. In 1865 he published a revised and corrected edition, and Pius IX expressed his praise and congratulations in a brief.

In 1850 Charles-François Baillargeon had resigned from his parish, for he had just been chosen agent, procurator, and vicar general of the Canadian bishops in Rome. He was well acquainted with their concerns, since he had presided over the deliberations of their councillors during a meeting in early May at Montreal preceding the council of the ecclesiastical province. Before the end of the year he had already settled a number of problems: the definition of the powers of the administrator of an ecclesiastical province, the reestablishment of the Quebec chapter, the annexation of the suffragan diocese of Newfoundland, obtaining the pallium for Pierre-Flavien Turgeon (he had become archbishop on 3 Oct. 1850 following Bishop Signay’s death), and securing clear instructions about various religious ceremonies. Above all he realized the futility of consulting Rome about everything; nobody there knew anything about the problems currently preoccupying the Canadian clergy – for instance, the secret society of Oddfellows and the moral seriousness of dancing the waltz or the polka. Matters to be dealt with by the first provincial council, planned for Montreal in August 1851, included the decree Tametsi, against clandestine marriages in parishes not officially constituted, and a general list drawn up by the bishops of special powers and indults to be requested of Rome.

Baillargeon considered his presence in Rome really superfluous. To mail reports or deliver them personally came to the same thing. If an agent was absolutely necessary, as Bishop Ignace Bourget* seemed to hold, it would be cheaper to choose one on the spot. In Rome, Bishop Bourget was regarded as a hasty man who made frequent bothersome requests for indults, and had compromised the Propaganda and the pope from whom he demanded the retirement of Bishop Signay. The bishop of Montreal, however, found Baillargeon’s own judgements “a little too precipitate and somewhat hasty.” These concerned, for example, Roman liturgy: “What a sorry affair their church services are!”; the mentality of the eternal city: “It is indeed at Rome that the law is made; but it is elsewhere that it is observed”; and the policy of the Vatican, which to Baillargeon seemed reactionary because the pope’s reforms were blocked by his entourage. In short, Baillargeon was not as fervent an ultramontane as Bishop Bourget.

Baillargeon was obliged to remain at Rome following his appointment as coadjutor to Bishop Turgeon, with the title of bishop of Tloa, a suffragan see of Myre, in Asia Minor (an appointment he did not in fact want). Rome could not fail to endorse the choice of the Canadian bishops who had extolled his virtues and his personal qualities: his profound knowledge in ecclesiastical matters, great zeal for discipline, firmness of character, judicious understanding of mankind, prudence and skill in business, all of which gave him the confidence of bishops, clergy, laity, and Protestants. He was consecrated in the church of the Lazarists on 23 Feb. 1851 by Cardinal Giacomo Filippo Fransoni, prefect of the Propaganda, assisted by John Hughes, archbishop of New York, and Charles-Joseph-Eugène de Mazenod, bishop of Marseille and founder of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. A 43-year-old prediction was being fulfilled. “Now, I believe in it,” Bishop Baillargeon wrote to his brother Étienne, the parish priest of Saint-Nicolas. One night in 1808 his mother, alone with her children and bewailing their sad future while praying to the Virgin Mary, had heard a voice: “Take comfort, two of thy children will be priests, and one will be a bishop.”

After saying goodbye to the pope in person, Bishop Baillargeon left Rome without regret. Great demonstrations of joy greeted his return to Quebec on 1 June 1851. The new bishop became superior of the Ursulines, the Hôtel-Dieu, and the Hôpital Général. In 1852 he replaced Bishop Turgeon in the pastoral visit to the Gaspé, Baie des Chaleurs, and Labrador. When the archbishop was stricken with paralysis, he became administrator of the diocese on 11 April 1855; he valued annual contact with the diocese, and in June and July regularly visited some 30 parishes. Bishop Baillargeon had always been firmly determined to foster education. Under his administration, 110 schools were opened in the 30 parishes and 40 missions had been founded. He also encouraged the coming of the Frères de la Doctrine Chrétienne and the Sisters of Jesus and Mary, as well as the founding of the Congrégation des Sœurs Servantes du Cœur Immaculé de Marie (Sisters of the Good Shepherd). He considered parish libraries a necessary complement to the schools, and he extended the Œuvre des Bons Livres, as constituted by the bishops of united Canada in 1850. In 1857 he inaugurated the École Normale Laval. A few years later he supported the founders of Université Laval in their struggle against certain followers of Bishop Jean-Joseph Gaume. This group included a visiting professor, the Lorraine priest Jacques-Michel Stremler, and his Canadian follower, Abbé Alexis Pelletier*, professor at the Séminaire de Québec, who wanted to give a Christian emphasis to classical studies by eliminating pagan authors. Strengthened by Rome’s approval, Bishop Baillargeon condemned the Gaumist ideas, which were being disseminated in articles and pamphlets. Stremler was relieved of his position in 1865, Pelletier resigned the following year and was welcomed at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière. Despite Bishop Gaume’s protests, the bishop of Quebec held out, and condemned two more pamphlets published in the same spirit.

Bishop Baillargeon supported the first two rectors of Université Laval, Louis-Jacques Casault and Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau*, in their opposition to the establishment of a rival university at Montreal; in their opinion this plan would lead to unfair and ruinous competition. Bishop Bourget, however, intervened three times at Rome, having adopted the conclusions of those responsible for higher learning (theology, law, medicine, and arts) at Montreal and Saint-Hyacinthe. The latter deplored the “inability” of Université Laval “to attract students . . . of the district of Montreal after their classical studies, and thereby to remove them from the dangers to faith and morals that they were exposed to at the Protestant university of the metropolis [McGill].” But Rome continued to support the delegates of Quebec. In 1870 Abbé Taschereau, now rector for a second time, proposed to Bishop Bourget that he set up a branch of Université Laval at Montreal for the chairs of law and medicine; this step was taken six years later.

Bishop Baillargeon also gave his attention to the intellectual training of priests. He set the same academic requirements as the university for the admission of candidates to the priesthood, and made young priests undergo an annual examination. He also made sure all priests were aware of the topics of the four annual ecclesiastical conferences. Concerned with spiritual renewal as well, he invited his colleagues each year to an eight-day retreat. He encouraged the founding of a hospice for old and infirm priests in the parish of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires at Quebec.

Bishop Baillargeon was president of the third and fourth provincial councils, and published the decrees enacted. The 1863 council dealt with a number of questions: faith and the principal obstacles to it – ungodly men, secret societies, bad books, mixed marriages; moral life and common failings such as cupidity, luxury, love of pleasure, drunkenness; the need for charitable works: poor relief, settlement, the collection of Peter’s pence (introduced in 1862), the Propagation of the Faith, and the Holy Childhood. His encouragement of the last three undertakings shows the universality of the bishop’s pastoral concerns. In 1868 the council fathers condemned intemperance and usury; they further proclaimed the temporal sovereignty of the pope and the Christian dimension in politics and elections.

Bishop Baillargeon had already intervened in 1858 and 1861 to improve the electoral climate. The advent of confederation led him to give his opinion on the constitutional evolution of Canada. Although he admitted that he was only the administrator of the metropolitan see, and had an “absolute incapacity for political affairs,” Bishop Baillargeon nonetheless had foreseen by June 1864 the best position to adopt, and he held it until 1867. The stand taken by his principal collaborators and councillors, Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, rector of Université Laval, and Charles-Félix Cazeau*, vicar general, was a deciding factor. The bishop resigned himself to confederation, without enthusiasm, for several reasons: the threat of representation by population in the parliament of the Province of Canada (which would mean an Anglophone Protestant majority); the impossibility of dissolving the union of the two Canadas because of problems of debt, tariff, and canals; the threat of annexation to the United States as the only other possibility; and finally, the participation of able French Canadian statesmen in the negotiations for a federal Canada. On the request of Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* of Trois-Rivières, Bishop Baillargeon urged all suffragan bishops to issue a special pastoral letter on the occasion of confederation. His own pastoral communication of 12 June 1867, including both a pastoral letter on confederation and a memorandum on the next elections, did more than simply remind people about obedience to the established order; the bishop discreetly stressed the advantages of the new constitution.

Baillargeon, who had yet to succeed the archbishop, often found himself in tricky situations. In 1864, for example, he had to warn Bishop Bourget to refrain, in the absence of the other bishops’ consent, from the revision of the 10-year-old provincial shorter catechism which he had announced. Until there was agreement, unity and uniformity had to be safeguarded in religious teaching. Besides, Baillargeon added, “we have made enough changes in discipline in recent years. People do not like reform in religious things. They are surprised, disturbed . . . and often scandalized.” In a report to Rome on 28 Oct. 1864 Bishop Baillargeon denounced the poor administration of Bishop Pierre-Adolphe Pinsoneault*, who had transferred his episcopal see from London to Windsor in 1859, and thereby greatly displeased his people. Bishop Baillargeon had gently admonished him at the time of the third provincial council in 1863; the poor bishop had appeared hurt and had rejected the accusations, but in the mean time the administration of his diocese had worsened.

Bishop Baillargeon became archbishop on 28 Aug. 1867, following Bishop Turgeon’s death, but he did not change his modest way of life in the slightest. On 2 Feb. 1868 he received the pallium from the hands of Charles La Rocque*, bishop of Saint-Hyacinthe. The diocese of Quebec had decreased in size after the formation of the diocese of Rimouski the preceding year. Bishop Baillargeon, who had thought of resigning as early as 1854 because of his health and had written to the pope in this regard, particularly in 1865, was to remain in office until his death, as the pope had advised.

He had gone to Rome in 1862 to settle an “important affair” on behalf of the Canadian bishops, and to respond to the pope’s invitation to take part in canonizing 26 Japanese martyrs. He had come back with the title of assistant to the pontifical throne and Roman count. Seven years later he returned to Rome to take part in the ecumenical council Vatican I, feeling “very small and very puny” among the giants of intelligence and knowledge. He would have liked to vote in favour of the dogma of papal infallibility, but the discussion proved longer than anticipated, and he had to return to Canada because of poor health. On the way he stopped at Vichy, France, to enjoy the waters.

Bishop Baillargeon was in Quebec by May 1870 and undertook his pastoral visit, but had to interrupt it because his health was deteriorating. His illness ended in death at Quebec, on 13 October. As he had not appointed a coadjutor, two priests, Charles-Félix Cazeau and Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, served as administrators. Expressions of sympathy poured in from all sides. In his will, Bishop Baillargeon had asked for a simple, unpretentious funeral, “expressly forbidding any distribution of gloves, black bands, or other tokens of mourning” to those present. Bishop Bourget performed the funeral service, assisted by four other bishops. The body of the deceased was buried in the cathedral on the same day, 18 October. The epitaph, which he had prepared himself, recalls in simple language the principal stages of his life.

Baillargeon, always obliged to pay attention to his health, passed away when he was still fully involved in pastoral work. An active priest and bishop, he constantly sought fresh inspiration for his mind and spirit. He was simple and sober in manner, and drew people to him. The stature of his successor, Bishop Elzéar-Alexandre Taschereau, has left Bishop Baillargeon’s pastoral work in the shadow; it was no less varied, realistic, enlightened, and wise.

AAQ, 20 A, VI, 64, 220; VII, 81, 83, 85, 177a, 177c, 179a, 220, 210 A, XIV, XXVIII, XXIX; CD, Diocèse de Québec, I, 146, 232; IV, 147–49, VI, 42f., 46, 48f., 51, 57f., 59; VII, 1786; IX, 43, 86, 118; 61 CD, Château-Richer, I; 61 CD, Notre-Dame de Québec, I, 90–92, 94, 99f., 114b, 121, 135. ACAM, RLL, 3, pp.228f.; RLB, 6, p.218; 295.099, 833–6, 833–7, 833–8, 833–9; 295.101, 823–13, 823–24, 833–42; 465.101. Archivio della Propaganda Fide (Rome), Scritture riferite nei Congressi: America Settentrionale, 6 (1849–57), ff.608f. ASQ, Évêques de Québec, 217E. Mandements des évêques de Québec (Têtu et Gagnon), IV, 223, 224–25, 245–46, 249–53, 264–65, 273–77, 293–94, 311, 321–23, 363–69, 381–82, 383–90, 409–19, 425–27, 431–33, 446, 457, 571–75, 579–82, 587–91, 615–48, 695, 730–31. Monseigneur Baillargeon, archevêque de Québec: sa vie, son oraison funèbre prononcée à la cathédrale, son éloge dans les églises de Québec et ses funérailles, etc., [C.-E. Légaré, édit.] (2e éd., Québec, 1870). Le Canadien, 4 janv. 1836. Henri Têtu, Notices biographiques: les évêques de Québec (Québec, 1889), 617–43. Carrière, Hist. des O.M.I., I, III, IV. Jacques Grisé, “Le premier concile provincial de Québec, 1851” (mémoire de des, université de Montréal, 1969), 30, 46–47, 51. Lemieux, L’établissement de la première prov. eccl. Honorius Provost, “Historique de la faculté des Arts de l’université Laval, 1852–1902” (thèse de ma, université Laval, Québec, 1952). T. [-M.] Charland, “Un gaumiste canadien: l’abbé Alexis Pelletier,” RHAF, I (1947–48), 195–236. Armand Gagné, “Le siège métropolitain de Québec et la naissance de la confédération,” SCHÉC Rapport, 34 (1967), 41–54. Léon Roy, “Où Mgr Baillargeon est-il né ?,” BRH, LI (1945), 127–32.

Cite This Article

Lucien Lemieux, “BAILLARGEON, CHARLES-FRANÇOIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baillargeon_charles_francois_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/baillargeon_charles_francois_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lucien Lemieux |

| Title of Article: | BAILLARGEON, CHARLES-FRANÇOIS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |

![[Mgr C. - F. Baillargeon] [image fixe] Original title: [Mgr C. - F. Baillargeon] [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.3881.jpg)