As part of the funding agreement between the Dictionary of Canadian Biography and the Canadian Museum of History, we invite readers to take part in a short survey.

MORRIS, WILLIAM, businessman, militia officer, justice of the peace, politician, and school administrator; b. 31 Oct. 1786 in Paisley, Scotland, second child of Alexander Morris and Janet Lang; m. 15 Aug. 1823 Elizabeth Cochran of Kirktonfield, parish of Neilston, Scotland, and they had three sons and four daughters; d. 29 June 1858 in Montreal.

William Morris, champion of the Church of Scotland in the Canadas, was the son of a well-to-do Scottish manufacturer. He was brought up in comfort in Paisley where he attended the local grammar school. In the spring of 1801 the Morris family, encouraged by friends in Upper Canada and armed with a letter of introduction to Lieutenant Governor Peter Hunter*, set sail for Canada in search of increased wealth. After some hesitation William’s father ventured his capital on the import-export trade between Montreal and Scotland. But in 1804 and 1805 he suffered severe financial reverses and shortly thereafter retired to a farm near Elizabethtown (Brockville), Upper Canada. There, amid heavy debts, he died in 1809. William, who had returned with the family to Scotland in 1802 and remained there with his mother, sister, and younger brother James* for nearly four years, had come back to Canada in the fall of 1806. With his elder brother Alexander, he set out to repay their late father’s creditors and recoup the family fortunes. Not destitute, yet financially unable to engage in the transatlantic trade as importers or wholesalers, they opened a store in Elizabethtown. They became two more of those small merchants in Upper Canada who served as middlemen between the mercantile houses of Montreal and the Indians, loggers, and settlers peopling the edge of the wilderness.

On the outbreak of the War of 1812 William obtained a commission as ensign in the 1st Leeds Militia. He took part in a number of operations culminating in the battle of Ogdensburg, N.Y., in February 1813 when he was detailed by Lieutenant-Colonel George Richard John Macdonell* to lead the successful assault on the old French fort. The following year he resigned from the militia to return to the family business. The war had been an exciting interlude, one which convinced him that Canadians were fundamentally loyal to the crown and capable of defending their country.

The brothers, looking for new commercial opportunities, decided to open a second store in the proposed military settlement at Perth. In 1816 William left Alexander in charge of the store in Brockville and travelled to Perth where hard work, frugality, and a keen eye for business drove him up the ladder of success. It was not long before he was the largest merchant in town, and he was soon deeply involved in local real estate. In partnership with Alexander, then with their younger brother James, and by the late 1830s acting independently, William slowly and persistently expanded his speculation in land into the rest of eastern Upper Canada and then right across the province. Mindful of their father’s problems, the Morris brothers were careful never to overextend themselves or to concentrate too heavily in any one enterprise. William wisely invested his excess capital from his land speculation and store in the new Canadian banking industry. Not all his ventures were to prove successful, however. Efforts to provide for navigation on the Tay River between Perth and the Lower Rideau Lake culminated in 1831 in the incorporation of the Tay Navigation Company, behind which Morris was the leading spirit and chief stockholder. The first Tay Canal was opened in 1834, but the company was plagued by lack of funds, and the canal works ultimately fell into decay.

By the 1820s Morris had become a prominent figure in the Perth area. Commissioned a justice of the peace in 1818, he spearheaded the successful campaign the following year to obtain a seat in the House of Assembly for the Perth region. In the area’s first general election in 1820 he was swept into office. A conscientious constituency man, he held the seat for Carleton and later for Lanark without trouble until his appointment to the Legislative Council in 1836 removed him from elective politics. Morris was named lieutenant-colonel of the newly formed 2nd Regiment of Carleton militia in 1822 and remained active in the militia for more than 20 years. During 1837–38, as senior colonel in Lanark County, he twice called out detachments to suppress rebellion and oppose invasion and on one occasion went in command himself. Successful businessman, militia colonel, and leader of the local conservative forces, William Morris was a man to be both courted and feared.

In the assembly Morris aligned himself with like-minded members such as John Beverley Robinson*, with whom he led the movement to expel the American-born reformer Barnabas Bidwell* from the house in 1821–22. An able parliamentarian and born tactician, he was one of the work-horses of the legislature who could be counted upon when the division bells rang. Although in time he became a leading force in the assembly, he never entered the charmed circle of “family compact” members who held official portfolios. Indeed, he came to have an intense hatred for them despite the many ideological assumptions they held in common.

Superficially, the reason for Morris’s alienation from the predominantly Anglican conservative élite lay in his championship of the right of the Church of Scotland’s colonial offshoots to a share in the clergy reserves. But his advocacy of the cause far exceeded his religious commitment. The clergy reserves for Morris, and for many other Scots, were the symbolic battleground in a struggle over whether the British empire would be uninational or binational in character. Until his death Morris publicly held steadfast to his triple belief that it was the Church of Scotland which gave form and substance to Scottish society, that the resultant Scottish nation was England’s coequal partner in controlling and developing all parts of the empire acquired since the union of 1707, and that Scots Canadians were the heirs of this patrimony in the Canadas. It was this intense Scots nationalism that set him at loggerheads not only with many of his fellow conservatives but also with the leaders of most other ethnic, religious, and political groups in the community.

The issue broke into the open late in 1823. That summer Morris had visited Scotland after an absence of 17 years, married, and established contact with the Reverend Duncan Mearns, the convener of the colonial committee of the Church of Scotland. On his return to Upper Canada, Morris introduced a bill calling for local recognition of the Church of Scotland as one of the two national churches of the British empire and for the equal funding of the two, if necessary, from the clergy reserves. Though narrowly defeated in the Legislative Council through the efforts of the Reverend John Strachan*, the bill was sent as an address to the king from the assembly in January 1824. What Morris had done was to take up an issue that had had, until then, little interest for any save a small group of Anglicans and a handful of Presbyterian ministers and thrust it into the public domain of the assembly, the newspapers, and, ultimately, the hustings.

For the next 17 years Morris led the political battle for what he saw as the rights of Scots Presbyterians. To demonstrate their numerical strength and to refute the opinions and statistics of Strachan’s “Ecclesiastical Chart,” he sought to have a religious census taken in 1827. What Morris lacked, at first, was the backing of a strong, effective colonial church since Presbyterians were a scattered, doctrinally diverse, and largely unorganized group. He therefore supported the colonial committee of the Church of Scotland and a few local ministers such as Robert McGill and John McKenzie in their efforts to form a synod. These efforts culminated in 1831 with the creation of the Synod of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection with the Church of Scotland. Morris also pressed the home church to send out more ministers in order to bolster the synod’s importance.

In 1837 the synod, incensed over Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne*’s injudicious creation of 44 Anglican rectories the previous year, asked Morris to go to England to counter the seeming Anglican hegemony and to plead for equal and exclusive state recognition and funding for the two churches. Soon after arriving in London, however, Morris, sensing the reluctance of the government to ignore other Protestant groups, revised his stand and suggested that any government grant be divided into thirds, one part each for the Anglicans and the Scots Presbyterians, and the final third for any other Protestant groups thought deserving. Back in the Canadas he enthusiastically told the synod that the imperial law officers had declared the rectories illegal and that the Colonial Office and its secretary, Lord Glenelg, warmly supported the proposals he had put to them. His optimism proved premature; Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head* seized on the vague wording of Glenelg’s public dispatches to oppose the synod’s claims.

Over the next two years Morris consolidated support for his funding scheme among the clergy of his church, coordinated Scots Presbyterian pressure on the local administration and the British government, and attempted to weaken the confidence of the Colonial Office in Strachan and his allies. Settlement seemed near in 1839. The new governor-in-chief, Charles Edward Poulett Thomson*, determined to achieve the union of the Canadas and to resolve outstanding grievances in the colony, gathered around him a coalition of moderates, of which Morris was a key member. In return for Morris’s political support in the Legislative Council and his influence among Presbyterians, the governor backed his campaign to bring about the merger of the two largest Presbyterian bodies in the Canadas, the United Synod of Upper Canada and the Synod of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection with the Church of Scotland. After intense negotiations, during which Morris held out the prospect of a clergy reserves settlement whereby all ministers belonging to the amalgamated church would benefit, the merger was finally accomplished in July 1840. The British parliament modified the proposals, however, and awarded the Church of England twice the amount granted to the Presbyterians, basing its decision on the census of 1839 which incorrectly recorded twice as many Anglicans as Presbyterians. Morris rationalized away his misgivings. The right of the two churches to equal funding had been acknowledged, and he persuaded his church to accept the Clergy Reserves Act of 1840 as a vindication, in principle, of their position.

The long bitter fight over Scottish rights in the British empire was not the only issue that set Morris outside the controlling élite. His views on education were a source of contention as well. Morris first became publicly involved in educational matters at Perth in 1822 as a member on a board of the Court of Quarter Sessions authorized to distribute funds to the Bathurst District grammar school. By the late 1820s he had become a recognized authority on the distressing state of schooling in Upper Canada. Convinced of the efficacy of education to produce a stable, prosperous society, he pleaded for a comprehensive, state-controlled system of free common schools capped in each district by a grammar school providing a classical education. He was opposed to plans to create a provincial university, believing that until the infrastructure had been laid a university was superfluous. Those in need of higher education could, he maintained, go to Great Britain. Moreover, the proposed university, King’s College (University of Toronto), seemed destined under Strachan to become a bastion of Anglican power and yet another affront to his nationalism. When it became apparent in the mid 1830s that the college’s 1827 charter would not be revoked, Morris argued for a non-sectarian university. Soon after, he compromised by suggesting that two state-funded chairs of Anglican and Presbyterian theology be added to the university, and Lord Glenelg gave some encouragement to this idea. However, by 1839 even these moderate proposals seemed unattainable, and Morris began to fear that Scots Presbyterians would be excluded from administrative and teaching posts at the university during Strachan’s lifetime.

Just at this moment pressure within the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection with the Church of Scotland for some form of local theological training had reached its bursting point. A committee of the synod under William Rintoul asked Morris to obtain an act enabling it to establish a seminary. Morris turned from his frustrating struggle over King’s to the more positive task of creating a new institution. Within a matter of weeks he had escalated the original proposal into a draft charter for a Presbyterian college complete with an arts and science faculty. By the winter of 1839–40 he was demanding that the proposed college, to be built at Kingston, be named Queen’s College to emphasize its equality with King’s and to demonstrate to Upper Canadians the parity of Scots and English in the empire. When it became known in January 1840 that the provincial government could not authorize the use of this title without the consent of the crown, Morris persuaded the synod to apply for a royal charter. Throughout the next two years, as chairman of the board of trustees, he bullied and cajoled his church into active efforts towards setting up the new college. By the time the royal charter was granted to Queen’s in October 1841 it was clear that Morris, more than any other individual, was responsible for its foundation.

The battle had taken its toll. Morris never found it congenial to work with clergymen; he chafed at what he deemed their laziness and inefficiency and distrusted their apparent thirst for power. Continual clashes with his fellow trustees blunted much of his enthusiasm for Queen’s, and the disastrous financial plight of the college further dimmed his initial ardour. In the harsh light of economic reality it was clear that Queen’s would not, in the foreseeable future, be the great Scottish-style university he had envisaged. Disillusioned, he decided to send his eldest son, Alexander*, to Scotland to be educated. In February 1842 he stopped attending board meetings, and in July he resigned from his position as chairman.

This mood found Morris responsive to the suggestion put forward by the first principal of Queen’s, Thomas Liddell*, and a number of board members that the college be moved to Toronto and amalgamated with King’s. Morris quickly reverted to his earlier contention that in a new country where funds were scarce what was needed was one secular, state-supported university with two or more theological chairs. For the next half decade he advanced that cause, fighting for the university bills sponsored in turn by Robert Baldwin and William Henry Draper*. The disillusionment Morris felt over the Queen’s experiment was further deepened by the disruption of 1844, when the Presbyterian church split into two factions. It seemed to him that the ministers, in their myopic way, threatened to undo all that he had achieved at such great effort.

Morris found solace in the world of politics. After the union of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841 he had been appointed to the new Legislative Council, and the following year he was made warden of the Johnstown District. When most of the Executive Council resigned over the patronage issue in 1843, Morris pledged his support to the governor-in-chief, Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe*, took part in strategy sessions, and then retired to Brockville, his home since 1842, to await events. In September 1844 he accepted the receiver generalship in the Draper government and in the following election stumped the province, successfully rallying conservative Presbyterians to the governor’s banner. His astute business sense and eagle eye for economy made him a model receiver general, and in 1845 he moved to Montreal to be nearer his work. He later boasted that he had streamlined the department, introduced new procedures, and earned the government £11,000 of interest from his deposits of public money. In 1846 he accepted the post of president of the Executive Council and held both positions until May 1847 when he persuaded John A. Macdonald* to take over from him as receiver general. But illness dogged his footsteps, and he was not unhappy to use the opportunity afforded by the defeat of the government in 1848 to spend the next two winters in the West Indies in search of renewed health.

In 1851 the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection with the Church of Scotland became alarmed by moves to expropriate their lands and revenues set afoot in the assembly the previous year by James Hervey Price*. They begged Morris to go to London to defend the share of the clergy reserves that he had won for them more than a decade earlier. Though a tired, ill man, he could not resist the call of his church and once again undertook the weary rounds of the Colonial Office. The old phrases and claims were dredged up, but this time the government was not receptive. Undaunted, Morris began to meld a strong opposition from a variety of disparate groups, including Anglican bishops and Scottish nationalists in the House of Lords and conservative politicians in the House of Commons. Faced with this hostile array and beset by myriad other difficulties, Lord John Russell’s Whig government backed down. The Canadian proposal was shelved.

Heartened by this success, Morris became involved with Queen’s again. For the next two years, until a stroke finally forced him into seclusion, he absorbed himself in its problems. Through the years he had kept a close watch over his business concerns, including his store at Perth. Though he sold out to John Murray in 1852, Morris, and later his son John Lang Morris, retained an active interest in the store. When Morris died in 1858, he left an estate worth £37,000 in land, cash, and securities.

William Morris had recognized many of the social and political forces at work in the Canadas and had, on occasion, modified his stands accordingly. None the less he always remained true to his fundamental belief in the equal rights of Scots and English in the empire. His strong Scots Presbyterian identity not only helped shape the causes he championed, but set him at odds with many of his fellow conservatives in Upper Canada and, indeed, helped undermine the position of the colonial élite.

[Pamphlets by William Morris include The correspondence of the Hon. William Morris with the Colonial Office, as the delegate from the Presbyterian body in Canada, [ed. Alexander Gale (Niagara [Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.], 1838)]; A letter on the subject of the clergy reserves, addressed to the Very Rev. Macfarlan and the Rev. Dr. Burns and Reply of William Morris, member of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada, to six letters, addressed to him by John Strachan, D.D., Archdeacon of York, both published at Toronto in 1838; Facts and particulars relating to the case of Morris vs. Cameron, recently tried at Brockville (Montreal, 1845); and Observations respecting the clergy reserves in Canada (London, 1851). The “Journal of the Honourable William Morris’s mission to England in the year 1837” has been edited by E. C. Kyte and published in OH, 30 (1934): 212–62, and his West Indian diary appears as “Twilight in Jamaica,” Douglas Library Notes (Kingston, Ont.), 14 (1965), no.2.

The main source for Morris is the collection of his papers at QUA; the Alexander Morris papers in AO, MS 535 illuminate his land dealings. More fragmentary sources are the Edmund Montague Morris papers at PAC, MG 30, D6, and, at QUA, the William Bell papers, the Synod papers of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in connection with the Church of Scotland, and the Queen’s Univ. letters.

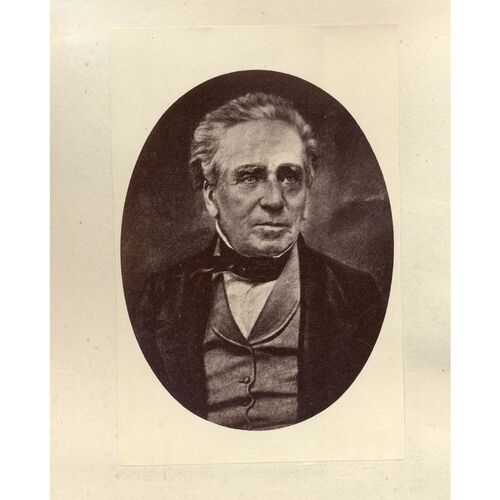

A biographical sketch and photograph of Morris appear in William Notman and [J.] F. Taylor, Portraits of British Americans, with biographical sketches (3v., Montreal, 1865–68), 1. Two more modern treatments are found in H. [M.] Neatby, “The Honourable William Morris, 1786–1858,” Historic Kingston, no.20 (1972): 65–76, and H. J. Bridgman, “Three Scots Presbyterians in Upper Canada; a study in emigration, nationalism and religion” (phd thesis, Queen’s Univ., Kingston, 1978). h.j.b.]

BLHU, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 17: 179. U.C., House of Assembly, Journal, 1821–35. Montreal Gazette, 10 July 1858. H. R. Morgan, “The first Tay Canal, an abortive Upper Canadian transportation enterprise of a century ago,” OH, 29 (1933): 103–16.

Cite This Article

H. J. Bridgman, “MORRIS, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morris_william_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morris_william_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | H. J. Bridgman |

| Title of Article: | MORRIS, WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | March 30, 2025 |

![[Hon. William Morris] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis Original title: [Hon. William Morris] [image fixe] / Studio of Inglis](/bioimages/w600.8520.jpg)