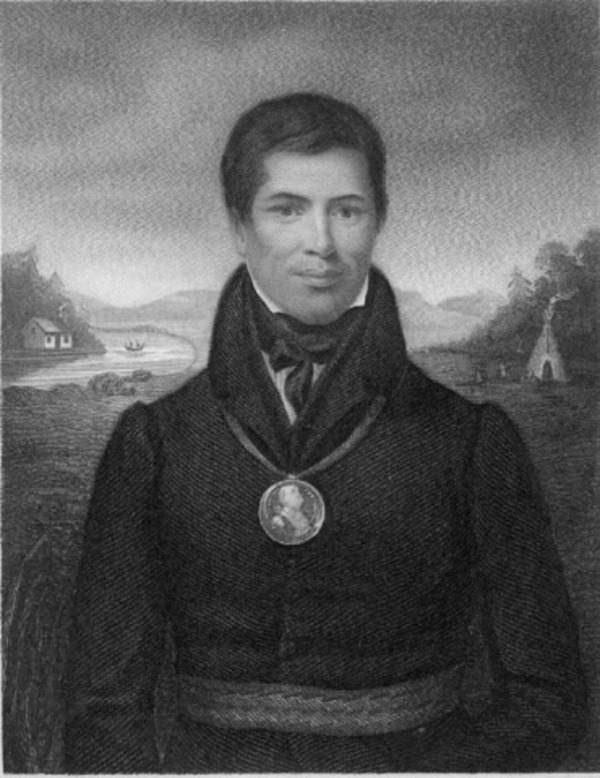

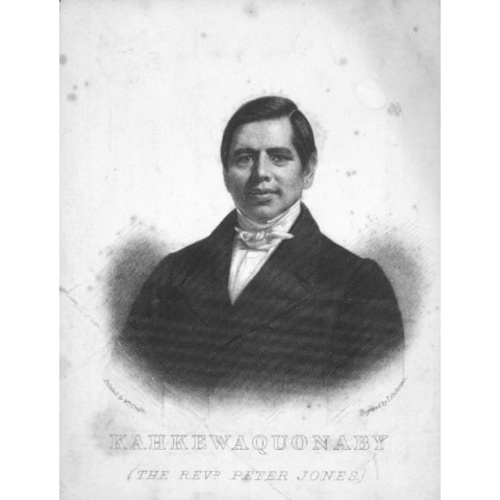

JONES, PETER (known in Ojibwa as Kahkewaquonaby, meaning “sacred feathers” or “sacred waving feathers”; also known as Desagondensta, in Mohawk, signifying “he stands people on their feet”), Mississauga Ojibwa chief, member of the eagle totem, farmer, Methodist minister, author, and translator; b. 1 Jan. 1802 at Burlington Heights (Hamilton), Upper Canada; m. 8 Sept. 1833 Elizabeth Field* in New York City, and they had five sons, four of whom survived infancy; d. 29 June 1856 near Brantford, Upper Canada.

Peter Jones was born in a wigwam on Burlington Heights, the second son of Augustus Jones*, a retired surveyor, and Tuhbenahneequay (Sarah Henry), the 22-year-old daughter of Wahbanosay, a Mississauga chief. Shortly after his birth he was given the name Kahkewaquonaby by Wahbanosay. Since Augustus was legally married to Sarah Tekarihogen (Tekerehogen), the daughter of the leading Mohawk chief, Henry [Tekarihogen*], he left the upbringing of Peter and his elder brother John* to Tuhbenahneequay. She raised them, teaching them the religion and the customs of her people, and they remained with her until 1816. Among the Mississaugas, Kahkewaquonaby learned how to hunt, fish, and canoe, and gained the reputation of being an excellent hunter.

Augustus Jones was interested in his sons’ welfare. In 1805 he had obtained a deed from the Mississauga band for a two-square-mile grant for each of them at the mouth of the Credit River, but he failed in his attempt to secure the government’s recognition of this transfer. Eleven years later, when he saw that the band at the western end of Lake Ontario was disintegrating (a result of declining population and scarcity of game), he took direct charge of his two Mississauga sons. He sent Kahkewaquonaby to a school near his farm at Stoney Creek. There the young Mississauga became known as Peter Jones, and learned to speak, read, and write in English. When Augustus moved with his Iroquois family to his extensive lands at the Grand River in 1817, he took Peter, now 15 and a strong youth, with him. On this farm Augustus taught him to care for his poultry and livestock, and to farm. Peter liked the Iroquois and he enjoyed his seven years among them. As a result of his stepmother’s membership in an important Mohawk family, he was adopted by that tribe and given the name Desagondensta. At home with his father, stepmother, and eight half-brothers and -sisters, Peter spoke English and never learned Mohawk.

While he was still a young man, Christianity did not appeal to him, although at his father’s request he was baptized in the Church of England in 1820. He later confessed, quite frankly, that one of the reasons that led him to accept baptism was the wish that “I might be entitled to all the privileges of the white inhabitants.” By his own admission his baptism had no effect on his life, since he continued to be “the same wild Indian youth as before.” At the age of 20 the ambitious Peter decided to return to school. Throughout the summer of 1822 he worked in a brickyard near Brantford to obtain the money to pay his fees. After studying arithmetic and writing the following winter, he returned to his father’s farm in the spring of 1823. Determined to succeed in the white man’s world, he hoped eventually to enter the fur trade as a clerk. He might well have done so had not a Methodist camp-meeting changed his entire life.

Purely out of curiosity Peter, with his half-sister Polly, attended a camp-meeting of the Methodist Episcopal Church in June 1823. During the five-day gathering in Ancaster Township, Peter became a convert, his soul touched by the preachings of the evangelical Christians. At the end of the meeting the Reverend William Case, seeing Peter rise to his feet to acknowledge his conversion, cried out with joy: “Glory to God, there stands a son of Augustus Jones of the Grand River, amongst the converts; now is the door opened for the work of conversion among his nation!”

When the Reverend Alvin Torry came to preach at the Grand River in 1823, he formed a native congregation around Chief Thomas Davis [Tehowagherengaraghkwen*] and Peter Jones. The young Mississauga encouraged his people to settle near the chief’s home, which became known as Davisville or Davis’s Hamlet. Many of Jones’s relatives came: his mother Tuhbenahneequay; his uncle Joseph Sawyer [Nawahjegezhegwabe*] with family, including Peter’s cousin Kezhegowinninne*; his half-sister Wechikiwekapawiqua and her husband, Chief Wageezhegome [Ogimauh-binaessih*]. By the end of the year Jones had begun teaching Sunday school and in the spring of 1824 he helped build a regular chapel for the growing Christian community. That summer he vowed to devote his life to missionary work. By the end of the summer of 1825 he had converted over half of his band to Christianity. That fall Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland offered to build for the converts a village of 20 houses on the west bank of the Credit River, in what is now Mississauga. Jones moved there early in 1826 and the village, called the Credit Mission, was completed by the winter of 1826–27. He was received on trial for the Methodist itinerancy in 1827.

During the summer of 1826 Jones had persuaded almost all those band members who were not yet Christians to enter the Methodist church. The faith of many Mississaugas in their own culture and religion had been shaken, as the life of one of their chiefs, Kineubenae*, demonstrates. In one generation they had lost more than half of their population and almost all of their hunting and fishing grounds. In their anxious state they looked to Jones for direction, entrusting him entirely with the conduct and management of their affairs. The native Christians felt that only he and his brother John, both English speakers, could deal effectively with the white missionaries and the Indian Department. In January 1829 the Credit band elected Peter one of their three chiefs, and he thus acquired a position of great influence, both in the band’s council and as an official spokesman.

The work of teaching his people to farm and to lead a settled way of life proved difficult, but he did have allies. His brother John, who worked as the village schoolmaster, became his most valuable assistant. Whenever they felt the band’s interests were threatened they went to York (Toronto) to petition the government. In 1825 they strongly urged that the white man’s intrusion on the band’s salmon fishing at the Credit River should end. When, the following year, the Indian Department failed to pay the band the full annuity owed under the terms of the land surrender by the Mississaugas in 1818 [see Kineubenae], they vigorously protested. Peter could also rely on his half-sister Polly, who lived at the mission, on John’s Iroquois wife, Kayatontye (Christiana), who taught the Mississauga women housekeeping, and on the family of his niece Nahnebahwequay*. In the village, his uncle Joseph Sawyer, Chief Wageezhegome, Samuel Wahbuneeb, and the three Herchmer brothers (William, Lawrence, and Jacob) had all “occasionally lived among white people” and possessed a knowledge of farming. By the fall of 1827 each family in the village had begun to cultivate a quarter-acre plot around their home and shared in the cultivation of a 30-acre field. Within ten years the community had cleared another 850 acres.

The news of the success of Peter Jones and the Methodists at the Credit spread quickly through the white community. When Jones went on tours in Upper Canada to raise money for mission-work, many whites came to hear him. According to Samuel Strickland*, his sermons in English were “both eloquent and instructive.” In response to his appeals, several white settlers gave individual contributions and as a group various churches gave presents. The Methodists of Vittoria, in Norfolk County, gave a stove to heat the schoolhouse, and those in York and on Yonge Street presented the band with a new plough.

Jones did not restrict himself to preaching to whites during his travels. In February 1826 he travelled to the Bay of Quinte, attracting Indian families from as far as 30 miles away, and the Methodists settled the resulting group of native converts on Grape Island. Among the Mississaugas led by Jones into the Methodist church from the Belleville and Kingston bands were Peter Jacobs [Pahtahsega*] and John Sunday [Shah-wun-dais*], both of whom became highly successful missionaries to the Indians. The stationing of capable white missionaries at the Credit, first Egerton Ryerson* in September 1826 and then James Richardson*, allowed Jones to carry out lengthier missionary tours to other Ojibwa bands.

The phenomenal success of the Methodists among the Mississaugas alarmed Lieutenant Governor Maitland and the province’s Executive Council, who had hoped that the native converts could eventually be won over to the Church of England. But Jones refused to abandon the Methodists. When John Strachan*, the powerful Anglican archdeacon of York, promised to increase the salaries of Peter and John beyond whatever the Methodists could possibly afford to pay them, in return for the brothers’ support, they both declined his offer.

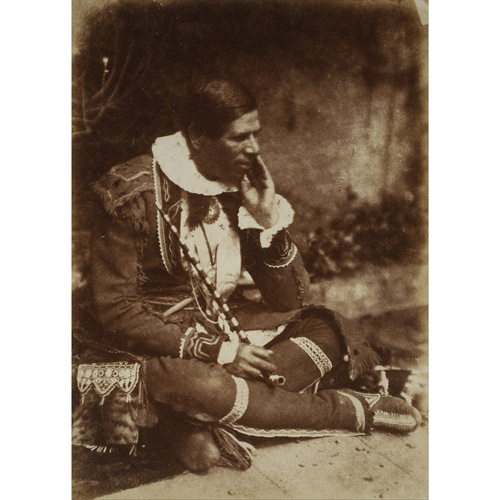

Throughout the late 1820s Peter continued energetically with his missionary work. With the help of his brother John he prepared the earliest translations of the Bible into Ojibwa. He successfully led into his church the Mississaugas at Rice Lake, the majority of the Ojibwas at Lake Simcoe, many at the Muncey Mission (southwest of London), and several Ojibwa bands on the eastern shore of Lake Huron. To raise money for the missions he accompanied William Case and several native converts in 1829 on a tour of the northeastern United States. In early 1831, along with George Ryerson*, he left on a missionary tour of Britain, and it proved a complete success. As he wrote back to John, “When my Indian name, Kahkewaquonaby, is announced to attend any public meetings, so great is the curiosity, the place is sure to be filled.” During his year abroad he gave more than 150 addresses and sermons attired in his Indian costume, and collected over £1,000 for the Methodist church’s mission-work. As well, he petitioned the Colonial Office on native land interests. He attracted great attention and on 5 April 1832, shortly before his return to Upper Canada, he had a private audience with King William IV.

On his English tour the celebrated Indian met Eliza Field, a pious Englishwoman who came to North America in 1833 to become his wife and lifelong companion in the mission field. She helped him copy out his translations of the scriptures into Ojibwa, taught the Indian girls how to sew, and instructed them in religion. Very supportive of her husband, who became a fully ordained Methodist minister on 6 Oct. 1833, Eliza worked to bring about the Europeanization of the Credit River band by giving them the skills and beliefs with which they could compete as equals with the whites. Peter and Eliza Jones believed unquestioningly that Christianity and European civilization represented man’s highest form of existence.

In the late 1830s Jones and the Methodists, with their allies in Britain, Sir Augustus Frederick D’Este and Dr Thomas Hodgkin of the Aborigines Protection Society, resisted the proposal, first made by Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head*, to remove the Credit band and other southern Indian groups to the barren Manitoulin Island. Behind Head’s proposal lay the desire to protect the Indians by removing them completely from white influences. But Jones and others knew that most of Manitoulin was too rocky to farm and that the Mississaugas would have to revert to hunting. On behalf of the Credit band, Jones went to England in late 1837. Because of the Colonial Office’s preoccupation with the rebellion of 1837–38, he was unable to discuss either the issue of removal or Indian claims to land titles with Lord Glenelg, the colonial secretary, until the following spring. Glenelg, however, refused to approve Head’s proposal. Impressed by the well-spoken native leader, he arranged a short audience for him with the young Queen Victoria in September 1838. With his wife, Jones returned to Upper Canada late that year.

Head had left the colony early in 1838 but the Methodists’ mission-work was soon plagued by more direct threats. In 1840 the fragile union of the Canadian Methodists and the British Wesleyans dissolved [see Matthew Richey*]. Peter and the majority of the Ojibwa Christians remained with the Canadians, but William Case and several of the bands sided with the Wesleyans. The split hampered the advance of the Methodists among the Indians, the two Methodist churches remaining apart until their reunion in 1847. As well, at the Credit, opposition to Jones’s leadership had arisen in the mid 1830s and continued through the following decade. Many Indians there objected to being made over into brown Englishmen. William and Lawrence Herchmer, in particular, fought to remain Indian as well as Christian. They protested against the harsh discipline imposed on the young. At issue too was Peter’s personal claim, which William Herchmer disputed, to a portion of the grant conceded by the band to him and his brother John in 1805. As a result of this internal strife, departures from the village became a serious problem.

The 1840s proved a difficult decade for Jones. From 1841 to 1849 he was stationed at the Muncey Mission, a demanding post with three tribes under his charge, Ojibwa, Munsee Delaware, and Oneida, all speaking different languages. His health began to deteriorate, and, as a calotypic photograph of 1845 clearly shows, he had gained considerable weight. For months at a stretch he made no entries in his diary, which comprises a significant record of missionary work among the Indians of Upper Canada. As a young man, he had spent a great deal of his time taking notes for a history of his tribe, but now he gave his manuscript little consideration. Even his third missionary tour of Britain, in 1845, failed to revive his spirits. He again attracted huge crowds, particularly in Scotland, but the constant travelling began to depress him. On 23 October he wrote to Eliza from Glasgow, “I am getting heartily tired of begging.” The British public was, it seemed to Peter, only interested in him as the exotic Kahkewaquonaby dressed out in his “odious” native custom, and not as Peter Jones, the civilized Indian that he had worked so hard to become.

Despite his weakened state, he continued to work for his people. In 1840 the band council had begun to consider the relocation of the Credit village because of the increasing severity of problems later enumerated by Jones: the pressure of white settlement, the scarcity of wood, the inconvenience of the village arrangement for farming, and the uncertainty surrounding his people’s claim to land at the Credit. Finally, in 1847, Jones led more than 200 band members to land donated by the Six Nations in the southwest corner of their reserve on the Grand River. He worked hard to ensure the early success of New Credit, as the reserve was named, and applied repeatedly to the government to have the funds from the sale of the Credit lands used for its development. As well, he frequently approached the Indian Department for support in securing farm supplies and erecting buildings. Probably through his initiative, a Methodist mission was established there by William Ryerson* in 1848.

After his people’s resettlement, Jones’s health failed to improve. Though in 1850 his physician ordered him to retire, forbidding him to travel or “to perform his clerical duties,” he continued to make long trips: in 1852 to the northern missions on the upper Great Lakes, the following year to a missionary meeting in New York City, and in 1854 to a convention in Syracuse, N.Y., which, Jones reported, was attended by 300 to 400 Indians. In 1851, after a brief period of residence in London, Upper Canada, the Joneses had moved into Echo Villa, a fine brick house they had built about 20 miles north of New Credit, near Brantford. Born in a wigwam, Kahkewaquonaby spent his last years in a Classical Revival style country home. His final illness began in December 1855 and was brought about by one of his frequent visits to New Credit. After completing the tiring journey in a lumber wagon, he felt unwell, but he was determined to attend the council meeting the following day and refused to return to Brantford. When the meeting was over he rode home through a drizzling rain. As soon as he reached Echo Villa he had to lie down. Despite consultations with Dr James Bovell* in Toronto, he never recovered and died on 29 June 1856.

The attendance of whites and Indians at his funeral illustrates the respect in which both communities held him. In its obituary notice, the Toronto Globe noted that the funeral procession was the largest ever witnessed in Brantford and included “upwards of eighty carriages besides a great number of white people and Indians on foot.” As Egerton Ryerson, a close friend for 30 years, stated in his funeral sermon, Jones had “enjoyed the esteem of, and had access to, every class of Canadian society.” Under the terms of his will, he left to his wife Echo Villa and a £1,000 policy from the Canada Life Assurance Company. The Indian missionary’s diaries were edited by Eliza and the Reverend Enoch Wood* and published in 1860 by Anson Green* as his Life and journals. Eliza edited his historical notes, which appeared in 1861 as History of the Ojebway Indians, an invaluable source for an understanding of the early Ojibwa converts in Upper Canada. In 1874 his third son and namesake, Peter Edmund (Kahkewaquonaby), a medical doctor, became a chief at New Credit.

In his lifetime Peter Jones accomplished much for his people. Before his conversion to Methodism, his Mississauga band had appeared to be on the verge of disintegration. However, as a result of his intervention and that of other native and white missionaries, the Credit River people and many other Ojibwa bands in southern Upper Canada successfully adjusted to the European presence.

Manuscript material by or concerning Peter Jones is available in a number of repositories. His papers in the Peter Jones collection at Victoria University Library (Toronto) include his manuscript for History of the Ojebway Indians . . . , his personal notebook (entitled the “Anecdote book”), and his diaries for 1827–28, as well as incoming and outgoing correspondence, including a volume of letters written to his wife, Eliza, between 1833 and 1848, copied in her hand. The collection also includes the Eliza[beth Field] Jones Carey papers. The Jones papers at the UCA include a manuscript autobiography entitled “Brief account of Kahkewaquonaby, written by himself” and his diary for 1829; the Credit Mission record-book is also at the UCA. Other records for the mission, as well as the Credit Band Council minutes, are found in the Paudash papers in PAC, RG 10, A6, vol.1011. Jones’s will is at the AO, RG 22, ser.155.

The published works of Peter Jones are extensive; only a representative selection is provided below. Additional titles and editions are listed in the National union catalog and in J. C. Pilling, Bibliography of the Algonquian languages (Washington, 1891), which has been reprinted as volume 2 of his Bibliographies of the languages of the North American Indians (9 parts in 3 vols., New York, 1973).

Jones’s diaries, edited after his death by Eliza Jones and Enoch Wood, were published as Life and journals of Kah-ke-wa-quo-nā-by (Rev. Peter Jones), Wesleyan missionary (Toronto, 1860). His History of the Ojebway Indians; with especial reference to their conversion to Christianity . . . , edited by Eliza, was issued posthumously in London in 1861.

The majority of Jones’s work, however, was published during his lifetime. His article concerning the relocation of his band appeared in the Christian Guardian of 12 Jan. 1848 under the title “Removal of the River Credit Indians.” Most of his other publications reflect his work as a clergyman and missionary. Numerous sermons and speeches given during his tour of Britain in 1831–32 went into print, and include the following pamphlets: Report of a speech, delivered by Kahkewaquonaby, the Indian chief, in the Wesleyan Chapel, Stockton-on-Tees, September 20th, 1831 (Stockton-on-Tees, Eng., 1831); The sermon and speeches of the Rev. Peter Jones, alias, Kah-ke-wa-quon-a-by, the converted Indian chief, delivered on the occasion of the eighteenth anniversary of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society, for the Leeds District . . . (Leeds, Eng., [1831]); and The substance of a sermon, preached at Ebenezer Chapel, Chatham, November the 20th, 1831, in aid of the Home Missionary Society (Maidstone, Eng., n.d.), a copy of which is available at the UCA. Several others were reproduced in the Wesleyan Preacher (London), among them sermons delivered “ . . . at the Welch Methodist Chapel, Aldersgate Street, on Sunday afternoon, January 22, 1832,” in volume 1 (October 1831–April 1832): 265–70; “. . . at Ebenezer Chapel, King Street, Bristol, on Sunday evening, February 5, 1832”: 422–27; and his “Farewell sermon delivered . . . at City Road Chapel, on Sunday evening, April 7, 1832, in aid of the funds of the Methodist Sunday schools,” volume 2 (April–October 1832): 108–15. A letter by Jones, dated 20 July 1831, appears on pages 270–72 of volume 1.

Peter Jones was also responsible for translating many religious works into Ojibwa, sometimes in collaboration with his brother John. He edited John’s translation of The Gospel according to St. John (London, 1831), and both brothers were involved in the translation of Matthew, published under the Ojibwa title Mesah oowh menwahjemoowin, kahenahjemood owh St. Matthew (York [Toronto], 1831). Peter’s translation of The first book of Moses, called Genesis was issued in Toronto in 1835. His translations also include Part of the discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada (Toronto, 1835), and a number of Ojibwa hymnals, among them Collection of hymns for the use of native Christians of the Chippeway tongue (New York, 1829); A collection of Chippeway and English hymns, for the use of the native Indians . . . (Toronto, 1840); and Additional hymns translated by the Rev. Peter Jones, Kah-ke-wa-qu-on-a-by, a short time before his death, for the spiritual benefit of his Indian brethren, 1856, issued posthumously in Brantford, [Ont.], in 1861.

Miniature portraits of Peter and Eliza Jones, painted in 1832 by Matilda Jones, are in Eliza’s papers in the Peter Jones collection at Victoria University Library. The 1845 photograph mentioned in the biography is one of several calotypes of him held by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (Edinburgh).

PAC, RG 10, A1, 712. [Egerton] Ryerson, “Brief sketch of the life, death, and character of the late Rev. Peter Jones,” Christian Guardian, 23 July 1856. Methodist Episcopal Church, Canada Conference, Missionary Soc., Annual report (York [Toronto]), 1826: 6; 1827: 12–13. Benjamin Slight, Indian researches; or, facts concerning the North American Indians . . . (Montreal, 1844). Samuel Strickland, Twenty-seven years in Canada West; or, the experience of an early settler, ed. Agnes Strickland (2v., London, 1853; repr. Edmonton, 1970), 2: 59. Christian Guardian, 25 Aug., 1 Sept. 1852; 13 April 1853; 18 Oct. 1854. Globe, 4 July 1856. Western Planet (Chatham, [Ont.]), 4 July 1856. “Calendar of state papers,” PAC Report, 1935: 265–68; 1936: 572–73; 1937: 601–8. Mary Byers and Margaret McBurney, The governor’s road; early buildings and families from Mississauga to London (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1982). Elizabeth Graham, Medicine man to missionary: missionaries as agents of change among the Indians of southern Ontario, 1784–1867 (Toronto, 1975). Egerton Ryerson, “The story of my life” . . . (being reminiscences of sixty years’ public service in Canada), ed. J. G. Hodgins (Toronto, 1883). D. B. Smith, “The Mississauga, Peter Jones, and the white man: the Algonkians’ adjustment to the Europeans on the north shore of Lake Ontario to 1860”

Cite This Article

Donald B. Smith, “JONES, PETER (Kahkewaquonaby, Desagondensta),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 24, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_peter_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_peter_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | JONES, PETER (Kahkewaquonaby, Desagondensta) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | December 24, 2024 |