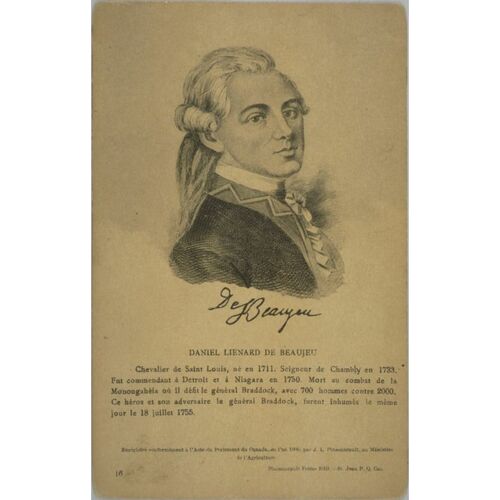

LIÉNARD DE BEAUJEU, DANIEL-HYACINTHE-MARIE, officer in the colonial regular troops, seigneur, entrepreneur; b. 9 Aug. 1711 at Montreal, son of Louis Liénard de Beaujeu and Thérèse-Denise Migeon de Branssat; killed in action near Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa.), 9 July 1755.

Daniel-Hyacinthe-Marie Liénard de Beaujeu grew up in Montreal and, like his father, joined the armed forces as an officer candidate while still in his teens. He may have spent some of his boyhood in the west, his father having been at posts such as Michilimackinac. The locations of his early service and the dates of his promotions are not recorded. At age 25, in Quebec, he married Michelle-Élisabeth, the daughter of François Foucault (4 March 1737). Of their nine children only two daughters survived into adulthood.

In June 1746 Lieutenant Beaujeu was among the leaders of a 700-man Canadian army dispatched to Nova Scotia to link up with forces expected from France for the capture of Louisbourg and Annapolis Royal [see La Rochefoucauld]. His 28,000-word journal of the 10-month campaign includes a detailed account of their greatest exploit. After a 150-mile march in bitter mid-winter, 300 Canadians and Indians attacked 500 New Englanders billeted in Grand Pré and forced their surrender after bloody fighting (11 Feb. 1747) [see Arthur Noble]. In several separate columns, they made a stealthy approach in the middle of the night. “A sentry who spotted us cried Who goes there? . . . We saw the watchkeeper come at once to the door. But the night was so dark, and we were hugging the ground so carefully, making no noise, that although we were within thirty paces, he considered it a false alarm and went back inside again. . . . In less than ten minutes we took the guardhouse. . . . All around we could hear musket fire. In every direction we could see men moving without being able to distinguish if they were our people or the enemy. . . . We had almost all lost our snowshoes and the amount of snow prevented us from moving smartly. . . . We would have been more gratified with our achievements if we had been able to learn that the other detachments had had as good success.”

With 20 years’ service, and recently promoted captain, Beaujeu was named commanding officer at Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) in 1749. He arrived there to take charge on 5 July. Niagara was the most strategic post in the pays d’en haut and Beaujeu apparently filled his role efficiently; still, he did not relish it. He knew sites farther west would yield more profit from furs. In December he reminded La Jonquière [Taffanel] that his predecessor as governor, La Galissonière [Barrin], had pledged, “in detaching me for Niagara, to station me the next spring in an advantageous post. . . .” He was full of complaints: his fort was crumbling into Lake Ontario, the garrison consisted of “veteran drunkards from Montreal,” he lacked skilled workers and vital materials for simple maintenance. Reaching a shrill pitch of eloquence, he likened his post to a “cattle pen.” Nevertheless, he was commandant of Niagara for the next several years.

In addition to directing military affairs he enforced trade regulations and tried to improve the portage road, but relations with Indians were his major concern. He had to try to preserve peace in the Great Lakes basin, on one occasion restraining some 40 Senecas who had decided to go on the warpath. Oswego was the most consistently troublesome problem. Beaujeu could not stop Indians who came down the Niagara portage from going on to trade their choicest furs at that New York outpost. To sustain French commerce, either Oswego had to be destroyed, he advised, or French prices for brandy and textiles had to come down to English levels.

Beaujeu’s last big assignment, in 1755, was to replace Claude-Pierre Pécaudy* de Contrecœur as commanding officer of newly built Fort Duquesne. His group left Lachine for the disputed Ohio country at the opening of navigation, 20 April, and arrived at Fort Frontenac (Kingston, Ont.) at the month’s end. Embarking in two sailing vessels, they reached Niagara in the second week of May.

The 500-mile supply line from Montreal to Fort Duquesne was complicated and still experimental. For his passage along the route, Beaujeu came armed with authority – in association with Pierre Landriève – to decide all arrangements necessary for supporting Canada’s southward expansion. Everyone seemed to be waiting for him, requesting orders, approval, solutions. Correspondence among the western posts mentioned, as a matter of high moment, that Beaujeu had just left or was expected. At Niagara he decreed where extraordinary reinforcements he might be needing were to come from, looked to his men’s health, bullied tons of supplies up the steep hill around the falls, dispatched 13 boats to row to Fort de la Presqu’île (now Erie, Pa.) and a gang of men to drive horses there through the woods, and still found composure enough to get down on paper proposals for making portage operations more efficient and for improving French bateaux. On 1 June he himself embarked on Lake Erie with 16 more boats. From Presqu’île Beaujeu sent orders back to Niagara to hasten 14 dozen muskets, and ahead to Ohio to muster all available craft up towards the headwaters. On 17 June, from Fort de la Rivière au Bœuf (Waterford, Pa.), he sent ahead wheat, bullets, and gunpowder. At Venango (Franklin, Pa.) he pressed into the reluctant hands of Michel Maray de La Chauvignerie a commission to build a regular fort there whether materials were available or not, along with a plan of what it should look like.

En route, Beaujeu was receiving urgent messages from the man he was coming to replace. Bring your men quickly, Contrecœur wrote in mid-May, let Philippe-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire expedite the supplies. Three weeks later ominous details were learned from an enemy deserter: 3,000 English and American soldiers, under Edward Braddock, were pushing towards Duquesne with over a dozen 18-pounder cannon.

His progress to the fort was the peak of Beaujeu’s career. Forty-four years old, active and incisive, he now assumed a leading role at the centre of continent-shaping affairs. Promotions had come rapidly. The Ohio valley was just such a fur-rich land as he had long yearned to win. He had business interests on the Labrador coast, had recently assembled three linked fiefs, and was angling for a fourth, which would make him seigneur of a 250-square-mile estate in the Richelieu valley (Lacolle).

At the end of June he arrived at the forks of the Ohio. Contrecœur remained commandant until the crisis cooled. The tempo of preparations increased as Fort Duquesne’s leaders weighed information about the enemy’s approach, wooed tribes whose manpower was needed to strengthen the French, and hammered out a strategy to keep the Ohio a link between Canada and Louisiana. They decided to fight the first battle well beyond the walls. At 8.00 a.m. on 9 July, Beaujeu led off a squad to ambush the British advance force of 1,500. He had 637 Indians, 146 Canadian militia, and 108 officers and men from the colonial regulars. As at Grand Pré, they would attack the enemy with inferior numbers. The French would have had to reconsider risking this initiative had not Beaujeu harangued the Indians – local Ottawas and Delawares, along with Hurons and Abenakis from the St Lawrence valley – into forgetting their fears of British numbers and cannon: “I am determined to go ahead and meet the enemy. What! Will you let your father go by himself? I am sure to beat them.”

About 1.00 p.m., before the ambush was prepared, Beaujeu’s party unexpectedly met the British in the woods. Contrecœur reported: “The enemy’s artillery caused our people to fall back twice, M. De Beaujeu was killed by the third discharge . . . just as our French and Indians were beginning to hold their own. This accident instead of discouraging our men only reanimated them. . . .” Rallied by Jean-Daniel Dumas*, the French and Indians put the English and Americans to rout – a victory that made the Ohio safe for French interests for another few years.

Beaujeu’s body was carried back to Fort Duquesne and buried there 12 July. His career had been one of ever greater success; he never knew defeat, old age, or failure. The geographical dispersion of his major battles – the Bay of Fundy and the Ohio valley – reveals him as an agent of an ambitious French empire in New France. But in the mid-1750s that empire was about to disappear.

ANQ, Greffe de R.-C. Barolet, 3 mars 1737; NF, Ins. Cons. sup., IX, 82–83; X, 6. Archives du Collège Bourget (Rigaud, Qué.), Famille Beaujeu, papiers de famille et notes par le Pere Alphonse Gauthier. PAC, MG 8, F50. Coll. doc. inédits Canada et Amérique, II. Inv. de pièces du Labrador (P.-G. Roy). “Lettres de Daniel-Hyacinthe Liénard de Beaujeu, commandant au fort Niagara,” BRH, XXXVII (1931), 355–72. NYCD (O’Callaghan and Fernow), XI, 303–4. Papiers Contrecœur (Grenier). Le Jeune, Dictionnaire. P.-G. Roy, Inv. concessions, IV, 263–67. Monongahéla de Beaujeu, Le héros de la Monongahéla; esquisse historique (Montréal, 1892), 3–4, 10–21. François Daniel, Histoire des grandes familles françaises du Canada . . . (Montréal, 1867), 255, 261–62. P.-G. Roy, Les petites choses de notre histoire (7 sér., Lévis, Québec, 1919–44), 3e sér., 239–42. Stanley, New France. C.-F. Bouthillier, “La bataille du 9 juillet 1755,” BRH, XIV (1908), 222–23.

Cite This Article

Malcolm MacLeod, “LIÉNARD DE BEAUJEU, DANIEL-HYACINTHE-MARIE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 16, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lienard_de_beaujeu_daniel_hyacinthe_marie_3E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lienard_de_beaujeu_daniel_hyacinthe_marie_3E.html |

| Author of Article: | Malcolm MacLeod |

| Title of Article: | LIÉNARD DE BEAUJEU, DANIEL-HYACINTHE-MARIE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 3 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1974 |

| Access Date: | April 16, 2025 |

![Chevalier Liénard de Beaujeu [image fixe] Original title: Chevalier Liénard de Beaujeu [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.5088.jpg)