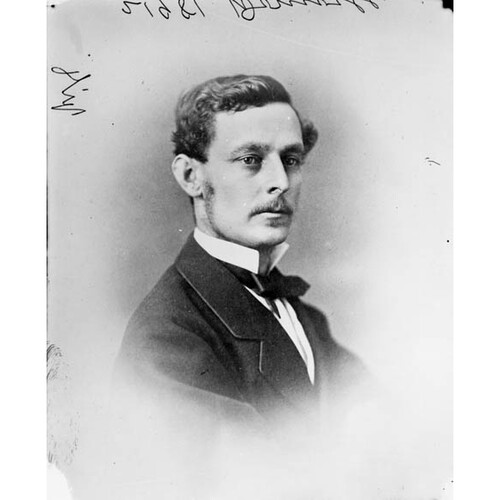

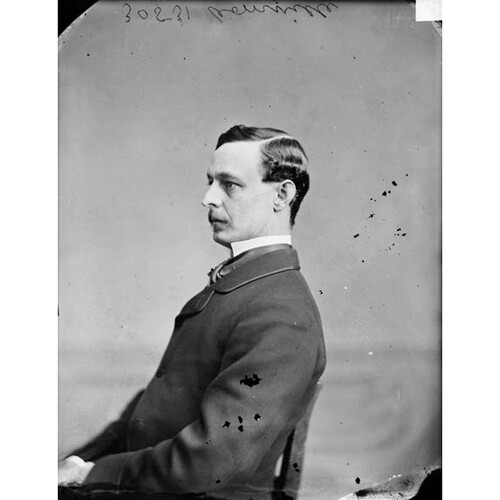

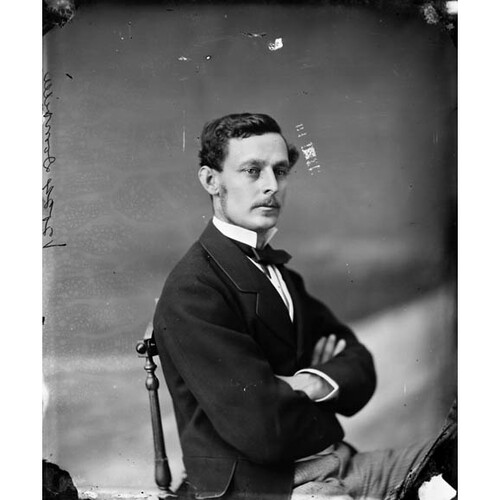

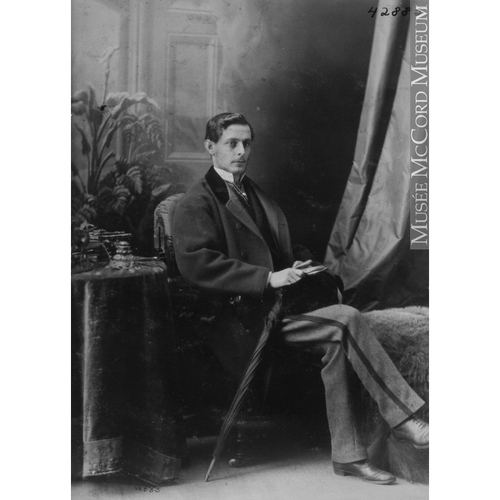

DOMVILLE, JAMES, businessman, politician, and militia officer; b. 29 Nov. 1842 in Belize, British Honduras (Belize), only son of James William Domville and Frances Usher; m. 25 April 1867 Anne Isabella Scovil in Portland (Saint John), N.B., and they had three sons and five daughters; d. 30 July 1921 in Rothesay, N.B.

James Domville was reputedly a descendant through his mother of an early archbishop of Armagh (Northern Ireland). His father, who would move to New Brunswick in 1875, attained the rank of major-general in the Royal Artillery in 1868, having served in India, British Honduras, and Barbados. The younger Domville was groomed for active service. He attended the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich (London), a school in Bonn (Germany), and the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr in France, but in 1858 he joined Michael Cavan and Company in Barbados. A division of Cavan, Lubbock and Company of Great Britain, the firm engaged in a general goods trade that served as Domville’s introduction to mercantile affairs. Henceforth his military career would be limited to the militia of New Brunswick, where he moved in 1866. Settling in the port of Saint John, he served in the militia during the Fenian raid that year and, in business, established a direct trade with the British West Indies that undoubtedly owed much to the contacts he had developed under Cavan.

As James Domville and Company, he dealt in teas and other goods from offices on the North Wharf in Saint John. Soon after his arrival he formed a partnership with merchant William Henry Scovil, whose daughter he married in 1867. Under the name Domville, Scovil and Company, the two men operated a variety of manufacturing businesses, including a merchant-bar and iron-rolling mill at Moosepath station, on the Intercolonial Railway northeast of Saint John, and a nail factory at nearby Coldbrook. Following his father-in-law’s death on 8 July 1869, Domville assumed full ownership of the company. Its several operations subsequently came to be known as the Coldbrook Rolling Mills Company, which, under Domville’s management, did quite well during the 1870s; federally incorporated in 1873, it paid a dividend of 12 per cent the following year. His interests eventually embraced resources and financial services. Through the General Oil Shales Company he urged the development of oil reserves in Albert County in southeast New Brunswick. In 1872 he helped establish the Maritime Bank of the Dominion of Canada in Saint John. He served as a director and a president, as did his father, but his reputation was tarnished by revelations in 1880 of his heavy indebtedness to the bank, which failed in 1887. Domville also served on the boards of two Montreal-based companies, Globe Mutual Life Assurance and Stadacona Fire and Life Insurance. His businesses were primarily located between the Bay of Fundy and the Ottawa valley, but as early as the late 1870s he was looking at opportunities in western Canada.

The expansion of his business enterprises led Domville into politics. Returned to the House of Commons in 1872 as the Conservative member for Kings – he established a home there (in Rothesay) in the early 1870s – he was defeated by George Eulas Foster* in 1882. An article in the Saint John Telegraph-Journal in 1929 would note that Domville had introduced a new style of electioneering that “did not appeal to the quiet thinkers” or “the rigid Baptists . . . [who] were seeing a new apostle in the suave, eloquent and persuasive Foster.” An Anglican, Domville may well have been less to the liking of local Baptists than Foster, who was one of their own. Moreover, as Foster put it, “his habits did not commend themselves to the Temperance wing of the electorate” in 1882. Domville, in fact, had been an open-fly participant in the famous drinking spree in the commons in April 1878, prior to the passage of the Canada Temperance Bill. But a deeper cause of displeasure lay in the National Policy of the Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald*. During a debate on its trade and industrial policies in 1879, Domville had nearly come to blows with fellow New Brunswicker Arthur Hill Gillmor*, the Liberal mp for Charlotte. Domville’s network of business associates in central Canada led him to support the government’s protectionist policies, yet voters in Kings came to realize that they were not fostering the development of local manufacturing. Domville’s defeat in 1882, then, was as much a result of trade issues as personalities. Thus began a 14-year absence from the commons in which he rethought his position and his allegiance to the Conservative party.

Domville’s time in Ottawa overshadowed his short career as a municipal politician between 1877 and 1880. During his term as an alderman on Saint John’s Common Council, he chaired its finance committee, but he gave local matters short shrift. Saint John newspapers did not lament his failure to be re-elected in 1880. The Daily Telegraph, for instance, remarked on 7 April 1880 that Domville had appeared more promising as a candidate than he was in office: “The intermittent attention that gentleman was able to give the business did not do much good to the city and scarcely added anything to his reputation. His mind is not adapted to a small business of a city like ours and since he began to be troubled with the Western fever he wisely resolved to leave the field to others.”

Yet it was also during this period that Domville launched his most enduring public work. The great fire of 1877 in Saint John, which had destroyed many private libraries as well as his commercial premises, prompted him to adopt the idea of a public library. Common Council had discussed such a project prior to the fire, and the disaster gave it impetus. Through Domville’s efforts, circulars were distributed requesting donations. The initiative brought in almost 3,000 books, which were committed to a city-administered trust in 1880. To a degree the books reflected Domville’s professional and personal interests. William Elder*, an mha for Saint John County and City, estimated that not more than half were worth including, “the others consisting mostly of statistical works, containing materials for the speeches of politicians.” At a meeting on 14 Sept. 1880 Domville described the collection as “nearly all works of reference” and noted that there were “a number of valuable books . . . which could not be procured in America.” Some were culled, but even so, when the library opened on 18 May 1883, it could offer 2,285 volumes.

A member of masonic bodies in Saint John and a president of the Kings County Board of Trade, Domville also maintained a local profile through the militia. He joined New Brunswick’s 8th Regiment of Cavalry in 1878, and was promoted lieutenant-colonel and its provisional commanding officer on 23 April 1880; he was confirmed as commander on 2 July 1881. The unit was designated the 8th (Princess Louise’s New Brunswick) Regiment of Cavalry in 1884. Domville offered it for imperial service in the Sudan that year, and again in 1896. Though the offer was refused both times, the profusive thanks of Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain in 1896 gave the regiment and Domville much publicity.

Sustained perhaps by his continuing local prominence, Domville remained determined to return to federal politics. For the elections of 1885 (a by-election), 1887, and 1891, he placed himself among the strange assortment of candidates billed as independents. In New Brunswick this group of adamant individualists were disappointed with the results of the National Policy and felt betrayed by the Macdonald government’s preference for Halifax as the leading transatlantic port over Saint John. At each election, however, Domville was defeated by Foster. His dissatisfaction finally led him into the Liberal camp, and in 1896, with Foster running in York, he re-entered the commons for Kings. Though denied his request to be made minister of militia and defence, he enjoyed a good relationship with Liberal leader Wilfrid Laurier*. He travelled to England with the prime minister for the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1897, and his professional experience made him an ideal choice as chair of the commons’ standing committee on banking and commerce. Some historians see Domville, certainly after his return to parliament, as a shameless self-promoter. Desmond Morton, for one, views him as “one of the most troublesome of the political colonels in the Jubilee contingent.”

In Ottawa, Domville found time to pursue commercial projects in Ontario, as well as the west. He was a vice-president of the Ottawa River Railway Company, incorporated in 1903, and a president of its successor, the Central Railway Company of Canada. (Neither line was built.) In 1897, with the support of a consortium in England, he had commissioned a firm in North Vancouver to build two steamers and he planned a rail line, later named the Edmonton, Yukon and Pacific, to service the newly discovered Klondike goldfields. These projects were ill-starred. The railway was surveyed but never laid, and the Lightning and the James Domville would meet untimely ends. The latter vessel, however, became the first steamer flying the British flag to reach the Klondike via the Yukon River, in October 1898. Although the North-West Mounted Police force there had been strengthened in February [see Sir Samuel Benfield Steele*], this additional demonstration of sovereignty helped quell American ambitions to claim the territory. The previous month Domville had arrived in Dawson overland from Skagway, Alaska, where he had been visiting the survey party tracing a route for the railway. He was no sooner in Dawson than his feisty character, which had led neighbours in New Brunswick to describe him as “cranky,” manifested itself. Asked by a reporter for his thoughts on the royalty that former commissioner James Morrow Walsh* had imposed on all gold mined in the Yukon, Domville remarked, “I don’t care a ——— for him. I am James Domville, member of Parliament for Kings County, New Brunswick. Why should I care for such fellows as Walsh?” Boasting that the James Domville had 20 guns on board, he declared he would unload and set up a power plant, regardless of the royalty. Though he departed before the steamer arrived, he left no doubt about his disdain for territorial authorities.

Domville gained even greater notoriety during the tensions and politics that complicated the reforms being undertaken by Laurier’s minister of militia and defence, Frederick William Borden*. Scheduled to retire from his command of the 8th in July 1898, Domville refused, in part because of his dislike of both Borden and his regimental second, Saint John newspaperman Alfred Markham, who had opposed his election two years before. District commander George Joseph Maunsell* held Domville to be a competent officer who deserved to have his command extended. Nonetheless, intense pressure was put on Domville by G. E. Foster, who charged him in the commons with a misappropriation of militia funds, and by the new general officer commanding, Major-General Edward Thomas Henry Hutton, who was appalled by Domville’s intransigence and by reports of his drinking and his “irregular” conduct in the Yukon. Only in August 1899, after being cleared of the charges, did Domville resign. Even then, he tried to keep his military ambitions alive by offering, later in the year, to raise a regiment for the South African War.

Defeated in the election of 1900, he still carried enough weight to be named to the Senate in 1903, in place of A. H. Gillmor, and to be made honorary colonel of the 8th Regiment in 1904, a recognition that had been refused by Governor General Lord Minto [Elliot*] in 1900. During the naval debate of 1909, with the Liberals favouring a Canadian naval service, he displayed strong conservative and imperialist sensibilities by supporting a direct contribution to the British navy. Near the end of his senatorial career, in a move that reflected his commercial knowledge of natural resources, he was named in 1920 to a special committee on the development of oil shales, iron ores, and coal deposits.

In February 1921 Domville’s residence outside Saint John in Rothesay burned to the ground. What was not destroyed fell victim to students from nearby Rothesay Collegiate, who, realizing they could not extinguish the blaze, started rescuing what they could. Unfortunately, possessions from the first floor, stacked on the grass, were stolen or crushed by items tossed from the upper storeys. A mattress landed on the Domvilles’ crystal and china, and a book knocked their son unconscious. Domville and his wife spent the remainder of their lives at the Kennedy Hotel in Rothesay. James Domville died on 30 July 1921 and, following religious services in Rothesay, his body was taken to Fernhill Cemetery in Saint John, where John G. Leonard, the worthy master of Albion masonic lodge, presided over the interment.

PANB, MC 1156. Daily Gleaner (Fredericton), 13 Aug. 1898. Daily Sun (Saint John), 20 Nov. 1883. Daily Telegraph (Saint John), 7 April, 15 Sept., 24 Nov. 1880. Kings County Record (Sussex, N.B.), 15 July 1997. Morning News (Saint John), 9 July 1869. Saint John Globe, 1 Aug. 1921. Telegraph-Journal (Saint John), 25 Nov. 1929. Atlas of Saint John, city and county, New Brunswick, comp. F. B. Roe and N. G. Colby (Saint John, 1875; repr. in Historical atlas of York County, N.B., and St. John, N.B., Belleville, Ont., 1973). Can., Dept. of Militia and Defence, Militia list (Ottawa), 1905; Parl., Sessional papers, 1885, no.7: 41; Statutes, 1873, c.121. Canadian annual rev., 1909. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Canadian who’s who, 1910. CPG, 1873, 1897, 1918. Directory, N.B., 1871. Free Public Library, Saint John Free Public Library: 50th anniversary of the Carnegie Building, 24 June 1904 to 24 June 1954 (Saint John, 1954). Robert Hook et al., Rothesay: an illustrated history, 1784–1920 ([Rothesay, N.B.], 1984). Douglas How, The 8th Hussars: a history of the regiment (Sussex, 1964). Lord Minto’s Canadian papers: a selection of the public and private papers of the fourth Earl of Minto, 1898–1904, ed. and intro. Paul Stevens and J. T. Saywell (2v., Toronto, 1981–83). Carman Miller, The Canadian career of the fourth Earl of Minto: the education of a viceroy (Waterloo, Ont., 1980). Desmond Morton, Ministers and generals: politics and the Canadian militia, 1868–1904 (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 1970). R. T. Naylor, The history of Canadian business, 1867–1914 (2v., Toronto, 1975). Norman Penlington, Canada and imperialism, 1896–1899 (Toronto, [1965]). St. John and its business: a history of St. John . . . (Saint John, 1875). Standard dict. of Canadian biog. (Roberts and Tunnell). Vital statistics from N.B. newspapers (Johnson). P. B. Waite, Canada, 1874–1896: arduous destiny (Toronto and Montreal, 1971). W. S. Wallace, The memoirs of the Rt. Hon. Sir George Foster, p.c., g.c.m.g. (Toronto, 1933). Who’s who and why, 1919–20. J. R. H. Wilbur, “The stormy history of the Maritime Bank, (1872) to 1886,” N.B. Hist. Soc., Coll. (Saint John), no.19 (1966): 69–76.

Cite This Article

Peter J. Mitham, “DOMVILLE, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 29, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/domville_james_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/domville_james_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter J. Mitham |

| Title of Article: | DOMVILLE, JAMES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | November 29, 2024 |