Source: Link

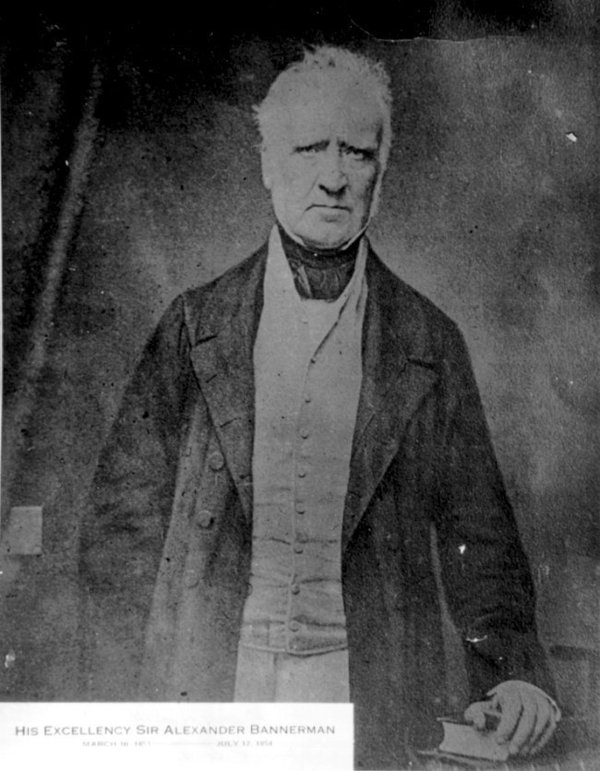

BANNERMAN, Sir ALEXANDER, merchant, banker, manufacturer, politician, and colonial administrator; b. 7 Oct. 1788 in Aberdeen, Scotland, eldest son of Thomas Bannerman; d. 30 Dec. 1864 in London, England.

Born into the family of a well-to-do Scottish wine merchant, Alexander Bannerman received a grammar school education and proceeded to Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he spent two sessions. In his early years he appears to have been noted for his outspoken Reform views and a penchant for practical jokes, which he never fully abandoned. After his father died in 1820 he and his brother Thomas took over the family wine business. As a result of his involvement in this and such other enterprises as banking, whaling, an iron foundry, and a cotton mill, Alexander became well known in Aberdeen. In 1832 he was acclaimed as the city’s member in the reformed House of Commons. He continued to sit as a Whig until he retired in early 1847, never having faced a serious challenger.

On 14 Jan. 1825 in London Bannerman had married Margaret Gordon, later identified as “Carlyle’s first love.” This remarkable woman was born in Charlottetown, P.E.I., a granddaughter of Margaret Hyde and Walter Patterson*, the Island’s first lieutenant governor. At school in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, Margaret Gordon had come to know the young schoolmaster Thomas Carlyle, who was attracted by her intelligence and wit. Yet she chose to marry her distant relative “Sandy” Bannerman, whom her biographer, Raymond Clare Archibald, described as “a young man of means and prominence, intellectually her inferior.” To Carlyle he was a “rich insignificant Aberdeen Mr. Somebody.” Noting Margaret’s intellectual gifts and social ambitions, Archibald suggested that possibly Bannerman’s “whole public career was largely shaped by his wife.” This may well be an accurate assessment, for the disparity between his capacities and those of Margaret was marked. His dispatches give no evidence of literary attainments or particular acumen, and in his business ventures he almost always failed.

Bannerman accepted appointment as lieutenant governor of his wife’s native colony late in 1850, after having declined previous offers of posts in the West Indies for fear of her health. He was knighted in February 1851 prior to his departure for Prince Edward Island. The colonial secretary, Lord Grey, instructed him to institute responsible government, which by this time had the overwhelming support of the Island population. Bannerman did this, and, aided by his Whiggish proclivities and jocular manner, quickly established warm personal relationships with members of the new Reform government led by George Coles*. When evidence of Orangeism appeared in the colony, in the form of the Orange oath published in the Islander in 1852, Bannerman, mindful of the sensitivities of the Irish Roman Catholic tenantry who supported the Reformers, issued a proclamation condemning the Orange Order. He also quarrelled with several of his Tory former executive councillors, including Edward Palmer*, John Myrie Holl, Thomas Heath Haviland, and Daniel Brenan*, over the rank and precedence due to them. Hence he became identified as a Reform partisan, a great favourite with one section of the populace, and roundly condemned by another.

It was in this context that Bannerman gave the Colonial Office cause to doubt his political wisdom and continued usefulness in Prince Edward Island. The Reform government was defeated at the polls in mid 1853 by the Conservatives under Holl and Palmer, but it did not resign. When the successful Tory candidates petitioned for an early session Bannerman declined to act on their request. The new government, finally installed in office in February 1854, was soon involved in a bitter dispute with Bannerman. Since the Franchise Act of 1853 had only received royal assent after the election, he argued that the assembly no longer represented the electorate; and if any by-elections were held, the new members chosen by the enlarged electorate would be seated beside men elected under the old, restricted franchise. For these and other reasons Bannerman insisted that another dissolution was necessary, and, defying the unanimous opinion of his Executive Council, called an election for June 1854. The Liberals, who had petitioned for another election even before leaving office, reaped the benefits of the enlarged franchise and won handily.

The Colonial Office had already decided to transfer Bannerman to the Bahamas, where responsible government had not been instituted. He wished to stay in Prince Edward Island until September but his superiors recognized that he had abandoned viceregal detachment and become partisan in his actions. He was not allowed to remain to greet Coles upon his return to office in 1854. He was, nevertheless, permitted to sojourn in the Boston area until the autumn in order that his wife would not have to face the full rigours of the tropical climate immediately upon her arrival. She proved able to withstand it for two years before returning to England.

In mid 1857, Bannerman returned as governor to a more northerly region, Newfoundland, where Margaret rejoined him. A few months earlier Newfoundland had induced Britain to abrogate a draft convention extending French fishing privileges in the colony and to promise that “the consent of the Community of Newfoundland is . . . the essential preliminary to any modification of their territorial or maritime rights.” Political leaders in a colony heavily dependent on the fishery considered this pledge a logical extension of the system of responsible government granted two years earlier. So confident was the political mood that Bannerman’s installation attracted little public fanfare. The appointment of a new governor, noted the pro-government Newfoundlander, no longer caused the fear which it had “under the defunct irresponsible system” when the governor was all-powerful, and it mentioned Bannerman’s positive role in the establishment of responsible government in Prince Edward Island.

Bannerman, however, maintained that “Responsible Government . . . increases rather than diminishes the Governor’s responsibility.” A governor could be impeached, but “his ministers cannot be . . . nor have they a particle of responsibility . . . excepting to their own constituencies.” He agreed that a governor must select his council from those who had the confidence of the people and consult them, but he was “by no means obliged to follow their advice if he considers that advice to be wrong.” Bannerman was appalled to find that his predecessor, Governor Sir Charles Henry Darling, even on an imperial issue like the fishery convention, had admitted he was powerless to impose the views of the imperial government. As early as August 1858 Bannerman forcefully explained his view on the governor’s prerogative to Liberal leader John Kent*.

Bannerman’s term began on a personally vexatious note. Soon after his arrival in St John’s his oath of office was “attacked” as offensive to Roman Catholics, who formed nearly half the colony’s population and dominated the governing Liberal party. More serious was a dispute over his salary. In 1855 the assembly had reduced the governor’s salary from £3,000 to £2,000 annually. The legislation, about which Bannerman evidently had no prior warning, came into effect only at his appointment. The government also began paying the salary in Newfoundland currency, which was worth slightly less than British sterling. Bannerman considered this action “not only irregular but illegal,” and appealed to law officers of the Colonial Office. They decided in his favour, and the Newfoundland government accepted the verdict.

The souring influence of the currency issue, coupled with Bannerman’s exaggerated views of his prerogative, was bound to create trouble between the governor and his independent-minded Executive Council. The prospect of conflict increased when Premier Philip Francis Little*, an experienced and astute political leader, resigned in 1858, and was succeeded by the fiery, intemperate John Kent. With evident distaste for colonial politics and little faith in the democratic process in Newfoundland’s sectarian, class-divided, and semi-illiterate society, Bannerman soon became convinced that Kent and his ministers were unfit to govern.

Bannerman was annoyed that the Newfoundland government refused the British request for positive proposals to settle the vexed issue of French fishing rights on the western shore, while still insisting on a virtual veto over any decision of the imperial authorities. He was convinced that the Executive Council was exploiting the issue for narrow political gain and warned Kent that he would never follow Darling’s precedent of informing his Executive Council of confidential dispatches from London on the French fishery question. Newfoundland politicians became alarmed when they learned in mid 1860 that negotiations were underway between Britain and France. Kent, who had been dropped from the Anglo-French commission on the fisheries in the spring of that year, complained bitterly at being excluded, though in reality the governor himself had little information on the subject.

Although diplomatically inept Bannerman was on sound constitutional ground in protecting the crown’s prerogative on a matter of such direct imperial interest as the fisheries. But he also frequently took issue with his ministers on domestic matters. On one occasion in 1858 Bannerman had insisted on conducting his own inquiry before acting on a council resolution to dismiss Financial Secretary James Tobin* for his criticisms of clerical influence on the Supreme Court. Kent angrily threatened to resign. On another occasion in 1860 Bannerman dismissed a magistrate at Trinity Bay recently appointed by the Executive Council, which then threatened resignation. Instead the council formally censured Bannerman for not giving the magistrate opportunity to answer charges. The Colonial Office concurred and criticized Bannerman’s procedure, though also supporting him in this situation. Bannerman, however, was not to be deterred by such criticism.

He again showed his resolve to be at the helm in late 1859 when the Executive Council failed to inform him about election riots which had occurred a few days earlier at Harbour Grace. When he received a report directly from the local magistrate, he charged that his council had deliberately “suppressed and withheld” documents intended for him. In the event of a recurrence of such an incident, he warned the council, he would “dispense with their services.” Reports from Harbour Grace convinced Bannerman that the riots were caused by attempts of Roman Catholic priests to control the election. Since the governing Liberal party was overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, Bannerman undoubtedly suspected his council of political motives. He was anxious to keep the political influence of the Roman Catholic clergy in check as well as maintain law and order. He had not dismissed the Liberal council realizing that the Liberals would not have been defeated in an ensuing election.

To Bannerman’s delight the political situation soon changed dramatically. In the spring of 1860 John Thomas Mullock, the influential Roman Catholic bishop of St John’s and until then a strong supporter of the Liberals, publicly criticized the government for reneging on a pledge to establish a steamship service around the island and for its allegedly corrupt administration of poor relief. Bannerman heartily concurred and was pleased that Mullock at last saw the incompetence and corruption of the Kent government.

With Bishop Mullock now realigned against the government and the Liberal party seriously divided over regulations to control poor relief, Bannerman was free to act more decisively against his ministers. During an assembly debate on 25 Feb. 1861 the receiver general, Thomas Glen*, announced the withdrawal of a bill to legalize the use of Newfoundland currency for all official transactions except the payment of salaries to the governor and chief justice. The bill was withdrawn because Bannerman insisted that it could only be operative when formally sanctioned by the British government. The bill would also have nullified a pending court case by two assistant judges to have their salaries paid in British sterling. Hugh William Hoyles*, leader of the Tory Protestant opposition, informed the house that the two judges, on his advice, had petitioned the governor against the bill. Kent, who had not been informed of the petition, charged that the bill had been defeated “by the minority in concert with the Judges and the Governor.”

When Bannerman read reports of Kent’s statement he immediately demanded to know whether the premier was accurately quoted. Kent curtly replied that the governor had no constitutional right to query him about his statements in the assembly. Bannerman now had the pretext he wanted and, after taking legal advice from Hoyles, he immediately dismissed the government and invited Hoyles to form the new government. Bannerman, as Kent and his colleagues were quick to charge, acted hastily and despotically. As a result the island was plunged into its worst political crisis since the introduction of representative institutions in 1832.

On Bannerman’s advice Hoyles reserved three positions in the council for Roman Catholics in order to avoid sectarian violence, but managed to convince only Laurence O’Brien, the president of the Legislative Council, to join his ministry. With standings in the assembly unchanged, Hoyles’ minority government was quickly defeated in a Liberal non-confidence motion. Bannerman obviously realized the importance for himself of a Tory victory in the general election, but the stakes were higher than he knew. The Duke of Newcastle, the colonial secretary, declared that “nothing can justify this extreme step except . . . success.” If a Conservative majority was elected, Bannerman would be vindicated but, if Kent and the Liberals won, the governor “must probably resign or be recalled.”

Bannerman probably expected Bishop Mullock’s support but after several weeks’ silence Mullock spoke forcefully against the reassertion in Newfoundland of Protestant Tory rule. To make matters worse the Anglican bishop, Edward Feild*, publicly took Bannerman’s side. Contests were held in only four constituencies (the remaining seats were filled by acclamation) and despite Bannerman’s military precautions, there was extensive violence in Carbonear, Harbour Grace, St John’s, and Harbour Main [see Mullock, Hogsett]. The overall result, pending the outcome of the two disputed districts of Harbour Grace and Harbour Main, gave the Tories 14 seats and Liberals 12. For the interim Bannerman had met Newcastle’s criterion of success. But it was a precarious victory, threatened by the further crowd violence in St John’s at the opening of the new assembly. Bannerman was convinced that the basic issue in Newfoundland was whether the colony was to be governed by the queen’s representative or by what Hoyles described as a “purely Romish despotism, marked by nominally free institutions.” Consequently it was imperative to control at least one of the disfranchised districts and thus maintain a Protestant Tory majority. In the case of Harbour Main a Tory-dominated committee of the assembly studied the election results and ruled in favour of the more independent Liberal candidates who had no clerical backing. In Harbour Grace a peaceful by-election in November returned two Protestant Tories, giving the Hoyles government an absolute and dependable majority.

The Colonial Office declined to take any action on a petition of some 8,000 Catholics, including Bishop Mullock, indicting Bannerman for constitutional despotism before the elections and responsibility for the ensuing riots, but it criticized some of his actions, although stressing the difficulty of his position had the Liberals been elected. This imperial disapproval, the personal strain of 1861, and Bannerman’s respect for Hoyles may have led the governor to be more cautious in the use of prerogative powers. When he retired in September 1864 he proudly emphasized that there had never been any disagreement between him and the Conservative government. A decade earlier he had written the same about his relationship with the Prince Edward Island Liberals as they were leaving office.

Bannerman planned to wind up his affairs at the Colonial Office and spend the remainder of his life in Aberdeen. But in London he contracted a bad cold, and, enfeebled, fell down a flight of stairs. Paralysis set in and he died on 30 Dec. 1864, predeceasing his wife by almost 14 years. They had had no children, and as Bannerman had never been careful with his personal finances, his widow passed her final years in considerably reduced circumstances. The influence of this strong-willed and capable woman over him in the exercise of his duties as governor must remain a matter for speculation. Certainly the least that can be said is that Bannerman, a former Whig mp, became a colonial governor with a strong belief in the prerogative of his office, and that in his political interventions he displayed remarkable obstinacy. In both Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland he came to be regarded by almost half the population as unacceptably partisan.

PANL, GN 1/3A, 1856–62; GN 1/3B, 1855–58; GN 9/1, 1861–69. PRO, CO 194/150–65; CO 226/79–83, especially 226/79, 28–35, 42, 76–77, 84–85, 89–90; 226/80, 172–74, 213–60, 387, 620–23; 226/81, 14, 47, 138–39, 142–43, 270–71; 226/82, 45–49, 68–69, 222–31; 226/83, 18, 41–43, 78–79, 87–93, 99–103, 119, 123–29, 141–42, 148–55, 182–83, 186, 189–94. Grand Orange Lodge of P.E.I., Annual report, 1867, 11–12. P.E.I., House of Assembly, Journal, 1854, 8; app.L. Examiner (Charlottetown), 14, 18 Dec. 1850; 4 Jan. 1851; 30 Jan. 1865. Islander, 8, 15 Aug. 1851; 30 April, 14 May, 4 June, 10, 17, 24 Sept., 1, 15 Oct. 1852; 10 Feb., 26 May, 9, 16, 23 June 1854; 27 Jan. 1865. Newfoundlander, 1857–61. Patriot (St John’s), 1860–61. Protestant and Evangelical Witness, 28 Jan. 1865. Public Ledger (St John’s), 1861. Royal Gazette (Charlottetown), 17 Dec. 1850, 21 July 1851, 24 Oct. 1853, 30 May 1854. Royal Gazette (St John’s), 1861. St. John’s Daily News and Newfoundland Journal of Commerce, 1861.

R. C. Archibald, Carlyle’s first love, Margaret Gordon, Lady Bannerman; an account of her life, ancestry, and homes, her family, and friends (London, 1910). W. R. Livingston, Responsible government in Prince Edward Island: a triumph of self-government under the crown (University of Iowa studies in the social sciences, IX, no.4, Iowa City, 1931). Prowse, History of Nfld. (1895). Robertson, “Religion, politics, and education in P.E.I.,” 92–93. George Sutherland, A manual of the geography and natural and civil history of Prince Edward Island, for the use of schools, families and emigrants (Charlottetown, 1861), 132–34. Thompson, French shore problem in Nfld. D. C. Harvey, “Dishing the Reformers,” RSC Trans., 3rd ser., XXV (1931), sect.ii, 37–44. W. S. MacNutt, “Political advance and social reform, 1842–1861,” Canada’s smallest province (Bolger), 124–27. E. C. Moulton, “Constitutional crisis and civil strife in Newfoundland, February to November 1861,” CHR, XLVIII (1967), 251–72.

Cite This Article

Edward C. Moulton and Ian Ross Robertson, “BANNERMAN, Sir ALEXANDER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 26, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bannerman_alexander_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bannerman_alexander_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Edward C. Moulton and Ian Ross Robertson |

| Title of Article: | BANNERMAN, Sir ALEXANDER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | April 26, 2025 |