The Fenians

Source: Link

Introduction

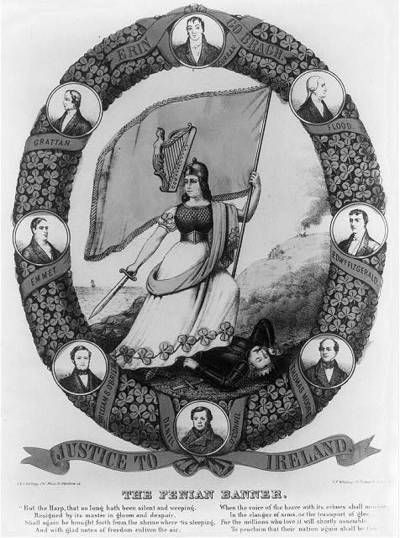

On St Patrick’s Day 1858, James Stephens founded a secret revolutionary organization in Dublin. Its purpose was to end British rule in Ireland and transform the country into an independent republic. In 1859 the leader of the movement’s American branch, John O’Mahony, gave the secret society the name by which it became generally known: the Fenian Brotherhood. Drawing on Irish mythological traditions, O’Mahony took the name from what he called the “Fiann na h-Eirenn,” which he viewed as bands of soldiers who defended ancient Ireland from foreign invaders. The Fenian Brotherhood in its modern incarnation became a transnational movement that had a wide following in the United States. After the American Civil War (1861–65) ended and Irish American soldiers were demobilized, Fenians in the United States split over the best strategy to achieve their objectives. One wing, led by O’Mahony, believed that Irish American republicans should send men, money, and materiel across the Atlantic to support a revolution in Ireland. Another wing, led by William Randall Roberts, argued that Irish revolutionaries should hit the British empire where it was most vulnerable – Canada. According to Roberts and his supporters, it was logistically impossible to send thousands of Irish American Civil War veterans into Ireland. But it seemed relatively easy to invade Canada – especially if the French Canadian inhabitants remained neutral and Irish Roman Catholics tacitly or actively supported an Irish American army of self-styled liberators.

A successful invasion, the Roberts wing believed, would open up all kinds of possibilities. Canada could become a base from which to disrupt British transatlantic commerce, or it could be a bargaining chip in negotiations to secure an independent Ireland. No less important was the possibility that an American-based Irish invasion of Canada would precipitate war between the United States and Great Britain. The Fenians operated on the assumption that the American government, buttressed by annexationist forces in the United States, would “recognize accomplished facts” (as Secretary of State William Henry Seward had supposedly told a Fenian leader in 1865). Anglo-American relations had deteriorated during the Civil War – the Union government criticized Britain for allowing Confederate ships to be fitted out in its ports and recognizing the belligerent status of the South – and those who followed Roberts were eager to take advantage of the situation. The mantra of Irish revolutionary republicans had long been “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity.” In the event of war, British troops would be pulled across the Atlantic at the very time that republicans in Ireland would draw inspiration from Fenian victories in North America and take up arms against Britain. War in Canada would result in freedom for Ireland.

That, at least, was the thinking.

In one respect, the pro-invasion Fenians were right: as events proved, even a limited military victory in Canada elicited an ecstatic response among Irish nationalists on both sides of the Atlantic. But they were wrong to think that the American government would simply look the other way during an invasion attempt, and they underestimated the extent to which Anglo-American relations were being repaired. They were also wrong in thinking that French Canadians would remain neutral and that most Irish Catholics would welcome them with open arms.

Ironically, the Fenians’ first invasion attempt was undertaken not by those who followed Roberts, but by their rivals under John O’Mahony. Fearing that he was losing ground to Roberts, O’Mahony decided to seize the initiative: in April 1866 he organized an attack from Eastport in Maine on Campobello Island in New Brunswick. Mistakenly believing that the island was disputed territory [see Thomas Henry Barclay], O’Mahony hoped that an invasion would trigger a war between the United States and Britain. The result: total disaster. The American authorities intercepted their weapons, the Royal Navy warships led by Major-General Charles Hastings Doyle were ready for them, and the New Brunswick militia answered the call. The invasion was beaten before it started.

It appeared that the invasion strategy had been utterly discredited. Not surprisingly, members of the Canadian government breathed a large sigh of relief, believed that the threat was over, and dropped their guard. But contrary to all British and colonial expectations, the Eastport fiasco gave the Roberts-led Fenians a new sense of urgency; they felt that they had to act quickly, before any remaining support drained away. Their commanding officer, General Thomas William Sweeny, warned Roberts that his men were unprepared, and would likely be defeated, but the Fenians pressed ahead anyway. During the night of 31 May 1866, a thousand men under the leadership of John O’Neill crossed into the Niagara peninsula from Buffalo, N.Y. On 2 June they defeated the Canadian militiamen under Lieutenant-Colonel Alfred Booker at the battle of Ridgeway, and routed a small force led by Lieutenant-Colonel John Stoughton Dennis at Fort Erie, Canada West (Upper Canada; present-day Ontario). Lacking reinforcements from the United States and facing superior British forces, O’Neill withdrew to the south. An attack at Pigeon Hill (Saint-Armand) in Canada East (Lower Canada; present-day Quebec) a week later was beaten back at the border [see William Osborne Smith].

In the United States, the Fenians regrouped, and began raising funds for another invasion attempt. Four years later, in May 1870, O’Neill was ready to try again. But the Fenian turnout was lower than he had anticipated, the forces of the new Dominion of Canada were prepared for action, and the American authorities began arresting Fenians (including O’Neill himself) for violating the neutrality proclamation of President Ulysses S. Grant. An attack from Vermont was quickly and easily repulsed at Eccles Hill, near Frelighsburg, Que., on 25 May, and a raid from New York the next day met the same fate. The strategy of freeing Ireland by invading Canada lay in ruins.

O’Neill, however, was not quite finished. In 1871 a former member of Louis Riel’s provisional government, William Bernard O’Donoghue, approached the Fenian Brotherhood in New York with a plan to invade Manitoba. When the Fenian leadership rejected the idea, O’Neill decided to organize his own filibustering expedition. Followed by around 35 men, and expecting significant support from the local Métis, O’Neill and O’Donoghue entered the province that October. Métis support never materialized, O’Neill and O’Donoghue were arrested, and the invaders were driven back to the United States. No further invasion attempts took place, although the idea remained alive in some Irish American quarters, and would resurface during the Irish Troubles of 1916–21.

In assessing the impact of the Fenian raids on British North America, Canadian historians have generally agreed that the attempt to capture Campobello Island helped to turn public opinion in New Brunswick towards confederation, and thus contributed to the defeat of Albert James Smith’s government by Samuel Leonard Tilley’s pro-confederation party. Since New Brunswick was essential to confederation, this change of attitude was of considerable importance. It is also generally accepted by historians that the Fenian raids in Canada in 1866 strengthened a sense of national feeling that consolidated the cause of confederation.

The raids created significant challenges for Irish Catholics in British North America, who risked being tarred with the Fenian brush. Most Irish Catholics remained loyal, but a significant minority supported the goal of an independent Irish republic. Irish Canadian Fenians were divided between those who rejected and those who supported the invasion strategy. The presence of Fenian secret societies in Canada alarmed the government, which in the winter of 1865–66 reorganized and expanded its secret police force to counter the perceived threat from within as well as from the United States.

Among the strongest supporters of the secret police, and of firm measures against Fenianism, was the politician Thomas D’Arcy McGee. A former Irish rebel who had repudiated his revolutionary past and become a Liberal Conservative, McGee argued that Fenianism was unrealistic, irreligious, and immoral, and should be given no quarter. Not surprisingly, McGee became a hate-figure for revolutionary Irish nationalists, who viewed him as a self-seeking traitor to Ireland. In the early morning of 7 April 1868 McGee was assassinated in Ottawa. Patrick James Whelan, an Irish tailor, was arrested for the murder; he was found guilty, and hanged. There was strong circumstantial evidence that Whelan was a Fenian and that he either shot McGee himself or was part of a hit squad. But Whelan always denied that he pulled the trigger, and historians remain divided over the question of his responsibility. Around 80,000 people attended McGee's funeral in Montreal, and his status as “a martyr to the cause of his country,” in Sir John Alexander Macdonald’s words, inspired a new generation of Canadian nationalists.

The works chosen for this thematic ensemble reflect the historiography of the time in which they were written (the 1970s and 1980s). Charles Perry Stacey, in his biography of John O’Neill, contends that the Fenian invasion strategy was “essentially stupid.” George Graham Mainer’s account of the battle of Ridgeway asserts that Alfred Booker’s men were driving back the Fenians until they began to run out of ammunition. Carl Betke, writing about the Canadian spymaster Gilbert McMicken, describes some of his correspondence with Macdonald about the Fenians as “comical.” Wilfred S. Neidhardt’s account of the Toronto Fenian leader Michael Murphy argues that “Fenian supporters in British North America probably never numbered more than a thousand.”

All of these views have been challenged by historians who have sought to explain the rationale behind the Fenian raids, reinterpreted the battle of Ridgeway, emphasized how seriously the Canadian authorities regarded the danger, and argued that the Fenians were a much larger minority of Irish Canadian Catholics than has previously been recognized. For these broadly revisionist views, please see the works listed in “Suggested Reading.”