Source: Link

WISE, JUPITER, labourer and servant; fl. 1783–86.

The earliest known record of Jupiter Wise comes from the “Book of Negroes,” which documents the Black loyalists, most of them formerly enslaved, who left New York during the British evacuation after the American Revolutionary War. On 8 July 1783 a British official described him as a “Stout” 25-year-old aboard the vessel Apollo, bound for Port Roseway (Shelburne), N.S.

The “Book of Negroes” often includes the “Names of the Persons in whose Possession they now are,” indicating the white loyalists with whom the Black migrants were associated. Wise was in the possession of “Heny Hotchinson,” probably Henry Hodgkinson, a New York army officer and hairdresser who appears on the passenger manifest for the Apollo with a woman and one servant. “Possession” was an ambiguous term and could mean protection, indentureship, or enslavement. Whatever his precise relationship with Hodgkinson, Wise was “Certified to be free by the Commandant,” Brigadier-General Samuel Birch, who issued certificates of freedom to Black loyalists leaving New York.

Nova Scotia

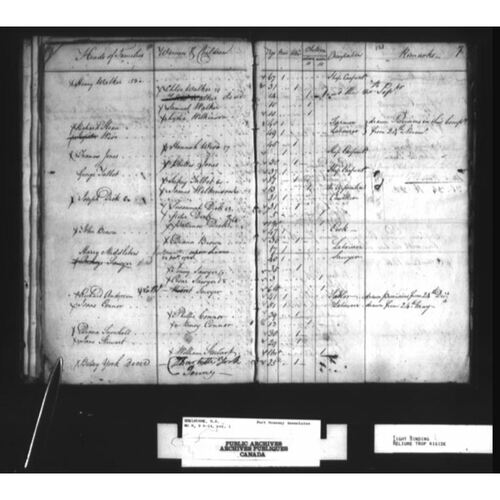

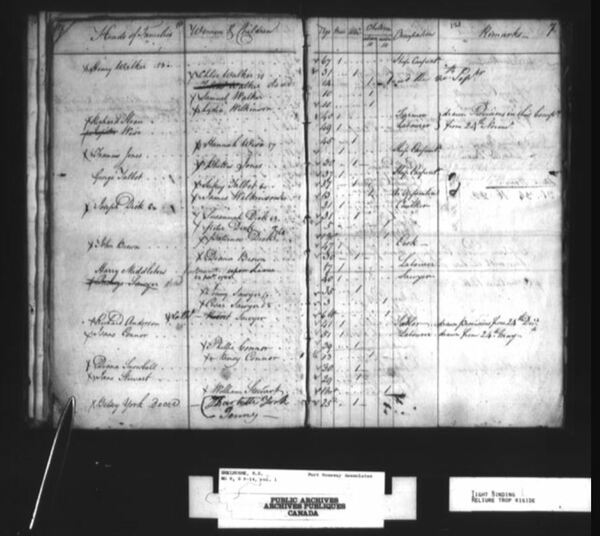

In Nova Scotia, Wise settled in Birchtown, a Black loyalist settlement just outside Shelburne [see Boston King*]. According to a 1784 muster book, he worked as a labourer and had drawn provisions from 24 Nov. 1783 as part of “Captain [Nathaniel] Snowball’s Company.” This document describes him as 49 years old, an age that is potentially more accurate for him since the “Book of Negroes” is known to contain rough estimations. In Birchtown he lived with a woman named Hannah Wise, who was 45. Hannah is listed as a dependant and was most likely his wife; unmarried women or women who had arrived without their husbands for whatever reason were recorded as “heads of families.” She does not appear in the “Book of Negroes,” but she may be listed under a maiden name or without a surname; the marriage, if indeed there was one, possibly took place in Nova Scotia. Jupiter’s name in the muster book appears to have been later crossed out, suggesting that he departed Birchtown while the record was still in use.

St John’s (Prince Edward) Island

Wise most likely left Nova Scotia just before or during the late spring of 1784. A muster roll taken that June in Charlottetown records the presence of Captain George Burns, who had settled on St John’s (Prince Edward) Island with a wife, two children, and two unnamed servants. The servants were probably Wise and a Black man named Joe: subsequent court records indicate that these two men were labouring for Burns shortly after he arrived. Why and how Wise left Birchtown and Hannah is unknown. Suffering miserable conditions in Nova Scotia, many Black loyalists indentured themselves to white loyalists and some were re-enslaved. Wise may have been forced into some such arrangement with Burns out of economic desperation.

Wise lived as part of Burns’s household on Euston Street in Charlottetown. The rest of what is known about him results from his journey through the island’s judicial system. In late 1785 he was accused of two assaults and a burglary. Records from these court cases provide fascinating details about his friendships and his conflicts, as well as insight into the daily lives of servants and enslaved people.

The case against Wise

Two affidavits from the case R. v. Wise present evidence against him. On 28 November a justice of the peace took carpenter and tavern keeper John Clark’s “Information against Jupiter Wise, for an Assault.” The next day a white soldier and servant named Silvester Petty provided his own indictment. According to these testimonies, on the evening of 26 November Petty went to Clark’s house in a panic, concerned that he “would be flogged to Death” for the disappearance from his own master’s house of items that had in fact been stolen by Clark’s Black servant Thomas Williams. In search of Williams, Clark and Petty passed by Burns’s house, where Clark saw “several Blacks, which made him suspect that said Thomas Williams might be among them.” He and Petty found Williams and Wise in the kitchen, “Sitting on a Bench playing at Cards, with a Number of Quires of Writing paper (seemingly damaged) and a Tin Cup standing upon them.” Clark collected these missing items and ordered Williams to go home. As Petty was leaving, Wise kicked him and told him to “get out of said Kitchen, calling him a Dam’d Rascal.” When Clark demanded an explanation, Wise replied that neither man “had any Right to go into his Masters House.” After Clark gave him a warning, Wise continued to object and Clark struck him with a stick.

As the two white men departed and passed in front of the house, Mrs Burns called Clark in and expressed her regret “that She had no White Man about the House to send with him, as She was apprehensive the Black People premeditated some design against him.” Almost immediately Petty, still outside, “was knocked down by two Blacks,” one of whom was Wise. When Clark went to assist, another servant named James joined the quarrel and all three Black men turned upon Clark. Wise struck him above the left eye with a stick. Petty’s statement ends at this point, but Clark’s goes on to say that he returned the blow. Wise dashed inside the house and returned with a cutlass, aiming for Clark’s head. Clark blocked the short sword with his own stick. At the threshold of the front door, Thomas Hazard (Haszard), a guest of Mrs Burns, then illuminated the scene with a candle, which “made the said Blacks to disperse” and quelled the fight.

On 30 November “A Free Black Man” named James Stevens (almost certainly the James involved in the brawl) gave evidence in the burglary case, Macdonald v. Wise, probably testifying in exchange for leniency. Curiously, he began his testimony with an account of a scheme, ultimately abortive, that he had entered into the previous summer with three enslaved men to escape the island by arming themselves and seizing Governor Walter Patterson’s sloop. Wise was not involved. After this digression Stevens went on to accuse Wise of having broken into the house of Michael McDonald (Macdonald) soon after Burns’s arrival in Charlottetown. Wise had asked Stevens for a tool called a gimlet and also a candle, promising to “Swill him with Rum which was not his Masters [Burns’s].” Having stolen two gallons of spirits (later valued at seven shillings), Wise hid them in a yard. He shared the rum with other servants and enslaved islanders at a hut belonging to a Mr and Mrs Rainey, where he and another man named Guy (enslaved to Phillips Callbeck) planned an elaborate party for the following night. Wise asked Burns’s son to write cards of invitation “which were sent round to their black acquaintances that evening and one to Mrs Pollard Capt. Gores Servant Maid.” Since Mrs Pollard is in this account set apart from Wise’s Black friends, she was presumably white, and her inclusion may indicate the interracial characteristics of his social circle. Wise and Guy provisioned the party with poultry, beef, potatoes, flour, butter, and rum. The revelry involved dinner, dancing, and drink, but when Callbeck came by and took Guy away, the gathering disbanded.

Verdict and sentencing

On 3 Feb. 1786 a jury heard the charges against Wise for two assaults and burglary, finding him guilty of a felony. The next day he was sentenced to death. Although the British legal system throughout the 18th century responded with capital punishment for misdeeds committed by all ranks of subjects and for even petty crimes, it is likely that Wise’s race and class had heightened concern among white islanders about his offences, which threatened established social relations. Wise spoke for himself in court and was the first person on the island to successfully plead the benefit of clergy, a legal mechanism that allowed first-time offenders of certain crimes to avoid the death penalty. He was instead sentenced “to be Transport’d for seven Years to some, one of his Majestys Islands in the Wt Indias.” Convicts in the Atlantic world endured deplorable conditions. To be spared a hanging did not mean Wise would receive much mercy. He and another prisoner escaped from jail but were apprehended in Pictou, N.S., in June and returned to island authorities. Wise’s fate, presumably in the Caribbean, is not known.

Jupiter Wise’s criminal activity must be understood in the context of his experience as a migrant, labourer, and servant. The evidence collected against him shows how he attempted to deal with his situation: he cultivated friendships, defended his space, organized festivities, lived generously, and assembled community. Through these efforts he sought to establish a meaningful life amid challenging circumstances.

Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), MG9-B9-14 (Shelburne hist. records coll., Muster book of free Black settlement of Birchtown, 1784, p.7 (copy available at heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_ reel_h984, image 83); MG23-D1, ser.1, vol.24 (Ward Chipman (senior and junior) fonds), Lawrence coll., Muster master’s office, Muster roll of the following disbanded officers, discharged and disbanded soldiers and other loyalists with their respective families that are now settled and preparing to settle at the Island of Saint John, taken by order of Major General Campbell at Charlottetown this 12th June 1784, p.100; heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_c9818, image 65); R2946-0-9 (Robert Wilkins coll.), Returns of men, women, children and servants in Captain Wilkins Company of loyalists on board of the ship Apollo …, 8th June 1783 (transcript available at immigrantships.net/1700/apollo17830608.html). National Arch. (London), PRO 30/55/100, Book of Negroes, Jupiter Wise (digital copy available at N.S. Arch., archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/page/?ID=38&Name=Jupiter%20Wise). Public Arch. and Records Office of P.E.I. (Charlottetown), RG5, ser.1 (P.E.I. Executive Council fonds, Minutes and orders-in-council), vol.1, p.95 (1 July 1786); RG6.1, ser.1, subser.1 (Supreme Court fonds, Minutes), vol.2, pp.2–3; RG6.1, ser.5, subser.1 (Supreme Court fonds, Case files 1770–1899), 157 (R. v. Wise (1785)); 219 (McDonald [Macdonald] v. Wise (1786)). L. C. Callbeck, The cradle of confederation: a brief history of Prince Edward Island from its discovery in 1534 to the present time (Fredericton, 1964). H. T. Holman, “Slaves and servants on Prince Edward Island: the case of Jupiter Wise,” Acadiensis, 12 (1982–83), no.1: 100–4. Jim Hornby, Black Islanders: Prince Edward Island’s historical Black community (Charlottetown, 1991); In the shadow of the gallows: criminal law and capital punishment in Prince Edward Island, 1769–1941 (Charlottetown, 1998). J. A. Mathieson, “Bench and bar,” in Past and present of Prince Edward Island …, ed. D. A. MacKinnon and A. B. Warburton (Charlottetown, [1906]), 121–42. Lorenzo Sabine, Biographical sketches of loyalists of the American revolution, with an historical essay (2v., Boston, 1864; repr. Port Washington, N.Y., 1966), 1. J. W. St G. Walker, The Black loyalists: the search for a promised land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870 (London, 1976). H. A. Whitfield, “Wise, Jupiter,” in his Biographical dictionary of enslaved Black people in the Maritimes (Toronto and Buffalo, N.Y., 2022), 235–36.

Cite This Article

Sarah Elizabeth Chute, “WISE, JUPITER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wise_jupiter_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wise_jupiter_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sarah Elizabeth Chute |

| Title of Article: | WISE, JUPITER |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |