Source: Link

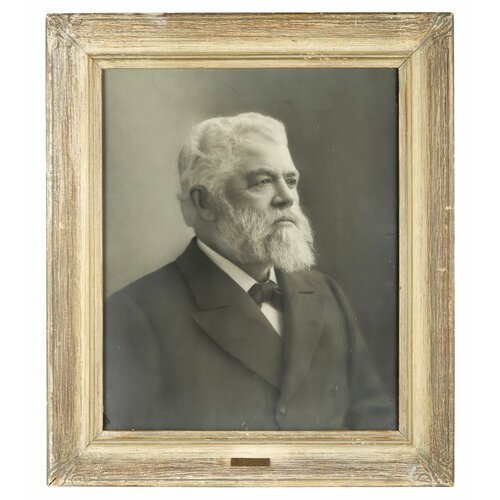

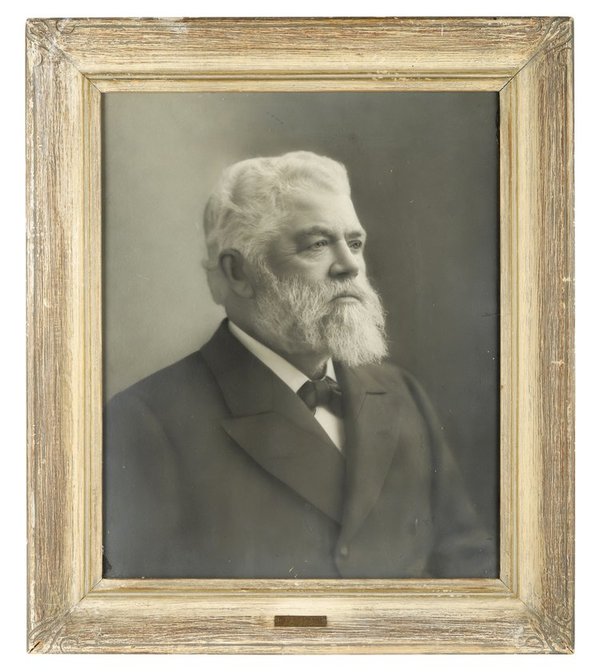

TUCKETT, GEORGE ELIAS, businessman and politician; b. 4 Dec. 1835 in Exeter, England, youngest son of Elias Tuckett and Mary ———; m. c. 1858 Elizabeth Leak, and they had four children; d. 19 Feb. 1900 in Hamilton, Ont.

In 1842 Elias and Mary Tuckett immigrated with their daughter and two sons to Hamilton, Upper Canada, where Elias found work as a tallow-chandler. Although in later life George Elias Tuckett regretted his lack of formal instruction, he had, by the standards of his class, a sound education – for a short time he attended a local private academy. Tuckett’s early employment remains unknown; he may have apprenticed as a shoemaker. In 1852, at the age of 17, he opened a shoe store in Hamilton but his business quickly failed. During the fifties and early sixties, he entered three partnerships with Hamilton tobacconists to make tobacco products. His associates probably supplied the capital and did the marketing while Tuckett engaged in manufacturing or supervised others in the work.

A short-lived partnership with David Rose followed his shoe-store venture. Tuckett’s health failed and he quit to work on a lake boat for several years. He returned to Hamilton to go into partnership with Amos Hill. In 1857 he struck out on his own again, hiring three or four men to make cigars. To retail his product, he opened a store in London. When he married – probably the following year – his wife also contributed to the business by selling cigars in the market and at fairs in Hamilton.

In 1862 Tuckett gave up cigar making to manufacture plug tobacco in partnership with Alfred Campbell Quimby, a Hamilton tobacconist. The American Civil War disrupted tobacco exports to Canada and protected the new industry. Quimby and Tuckett are reported to have gone behind Confederate lines to purchase Virginia tobacco, which could then be shipped north as Canadian property. The stress of such transactions affected Tuckett’s health and in early 1864 the business was dissolved.

The following year Tuckett and John Billings purchased the interest of Nathan B. Gatchell in the Hamilton Glass Works and took in three partners. Difficulties in marketing the glassware quickly disillusioned Tuckett and, after just one year, he decided to return to the manufacture of plug tobacco, this time with Billings. Their business prospered. By 1868 Tuckett and Billings employed 70 hands, more than either of the other two tobacco manufacturers in Hamilton. Three years later they doubled their plant’s capacity. In 1875 the credit reporter of R. G. Dun and Company judged the partners to be good risks. The value of their assets, including their factory, which had cost them $6,000 in 1866, was placed at $60,000 to $75,000. Tuckett possessed real estate outside the business worth $40,000 to $50,000, including a residence worth $16,000.

The partnership lasted until Billings retired in 1880. Tuckett’s elder son, George Thomas, and his nephew, John Elias Tuckett, then became partners in George E. Tuckett and Son. The nephew had for some time attended to the company’s branch in Danville, Va. In the late 1880s George Elias began reducing his active involvement in the firm and with incorporation in 1892 the day-to-day operations became fully his son’s responsibility.

Reorganization had followed shortly after the completion of a model factory in 1891. A comparison of this plant with the one built 20 years earlier reveals Tuckett’s attention to operational detail and his concern for efficiency. In the 1891 building, the raw tobacco was hoisted to the third floor and descended floor by floor through various processing stages until it reached the shipping room, whereas in the earlier plant the tobacco had moved up and down from floor to floor. With the principle of continuous flow in place, little adjustment was required when cigarette manufacturing began in 1896. Besides streamlining work organization in his new factory, Tuckett installed fire-escapes and provided lunch-rooms and separate wash-rooms for men and women.

With some success, Tuckett had been using paternalistic labour policies to promote loyalty among the approximately 400 workers in his employ by the 1880s. His voluntary introduction in 1882 of the nine-hour day as well as profit-sharing and bonuses brought him their goodwill and much favourable publicity. At the same time different terms of employment segmented the labour force, thereby enhancing his control of the work process. The terms conformed to separate stages in the production process. Tuckett believed that piece-rates for the most skilled workers, the rollers and plug makers, best sustained and increased production. If they wanted to earn the same or more income than other workers in the factory at large, they had to speed up their production. Their dependence on piece-rates made them the drivers of those paid daily rates.

The plug makers could not run the presses without prepared leaf. The rollers, who prepared the leaf for curing and pressing, hired and paid the child workers who stripped the leaf from its stem for them. Supervision of these unskilled and potentially least disciplined workers was in this way decentralized. Parents bargained with rollers to take on their children – supposedly 14 to 16 years old – and committed themselves to the good behaviour of their offspring. Bonuses at Christmas rewarded good performance during the year. The piece-workers received Christmas boxes or turkeys and cash prizes individually if their work was deemed meritorious. Workers paid at a daily rate were rewarded by a cash bonus in proportion to the company’s profits. The children were given 25 cents and a chance to win prizes of $20, $10, and $5. Much ritual attended the distribution of bonuses at Christmas. Tuckett reviewed the year, explained the reasons if firings had occurred, and read his factory rules. It was also an occasion for rewarding employees of 21 years’ service with the gift of a building lot and $225 (to be paid after a house had been built). Tuckett was also mindful of the importance of marketing his product and carefully developed and advertised brand names to build consumer loyalty. By the early 1870s Tuckett and Billings were manufacturing a dozen brands of plug tobacco, each of a particular grade, sold in tins under the T & B trade-mark. The most popular was Myrtle Navy Tobacco. Marguerite cigars were introduced in 1891 and T & B cigarettes in 1896.

The publicity arising from his success and his system of factory labour made Tuckett an attractive candidate for public office. His political innocence, however, rendered his political career mercurial. He considered himself a social radical and, as befitted a successful artisan, he believed in charting an independent political course. Originally a reformer, he was drawn to the Conservative party by the National Policy. Anticipating a federal election, local Conservatives prevailed upon Tuckett in 1895 to accept the nomination for one of the Hamilton seats. The Liberals feared his electoral appeal and offered to support him for mayor in 1896 – he had been an alderman in 1863, 1864, and 1884 – if he declined to stand for the federal election, and he agreed.

Tuckett ran on a municipal platform of good government and low taxes. He was, however, a target for Hamilton’s moral reform movement. He manufactured tobacco; he was accused of being a patron of saloons; as a director of the Hamilton Jockey Club, he abetted gambling; as a shareholder in the Hamilton Street Railway and a recipient of tax and water-rate exemptions for his factory, he benefited from the very municipal expenditures he claimed were too high. The last was the most serious charge: his $85,000 exemption on an assessed value of $129,000 cost the city $1,700 a year in revenue. Yet Tuckett won the election by a landslide. He had nevertheless alienated the Conservative party and, with no commitment from the Liberals to support him for mayor in 1897, his re-election bid collapsed. He lost decisively.

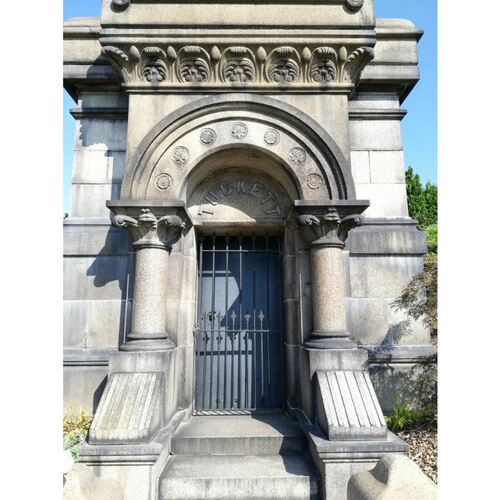

When he died in 1900, George Elias Tuckett was a socially prominent and very wealthy man. He was an Anglican and generous to his own congregation, a freemason, and president of the St George’s Society (1898). Besides considerable real estate, he had accumulated personal property worth $708,705, including nearly $375,000 in bank and other shares. At various times he had served on the boards of directors of the Bank of British North America, the Traders Bank of Canada, and the Hamilton and Barton Incline Railway Company, and he had been president of the Hamilton Steamboat Company. He also had invested in the Hamilton Street Railway and the Hamilton Steel and Iron Company. Though he may not have received an extensive education, Tuckett possessed an aptitude for adapting factory organization more efficiently to mass production and a willingness to experiment with labour relations. To these qualities, his success might be attributed.

Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 25: 286 (mfm. at NA). HPL, Clipping file, Hamilton biog., G. E. Tuckett; Picture coll., Hamilton portraits, G. E. Tuckett; Scrapbooks, H. F. Gardiner; A. W. Roy; Victorian Hamilton. Can., Royal commission on labour and capital, Report, Evidence – Ontario. Hamilton Spectator, 1871–1900. Palladium of Labor (Hamilton, Ont.), 27 Sept., 15, 19 Nov., 6 Dec. 1884. Times (Hamilton), 21 Feb. 1900. DHB. Hamilton directory, 1856–73, 1888, 1898–99. B. D. Palmer, A culture in conflict: skilled workers and industrial capitalism in Hamilton, Ontario, 1860–1914 (Montreal, 1979), 29, 189, 259. J. C. Weaver, Hamilton: an illustrated history (Toronto, 1982), 92, 111. P. R. Austin, “Two mayors of early Hamilton,” Wentworth Bygones (Hamilton), 3 (1962): 1–9.

Cite This Article

David G. Burley, “TUCKETT, GEORGE ELIAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 2, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tuckett_george_elias_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tuckett_george_elias_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | David G. Burley |

| Title of Article: | TUCKETT, GEORGE ELIAS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | January 2, 2026 |