Source: Link

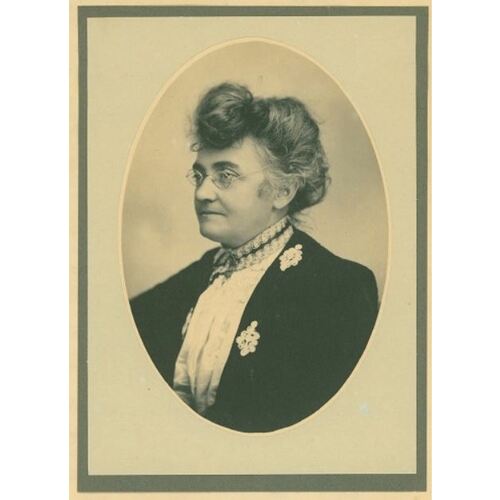

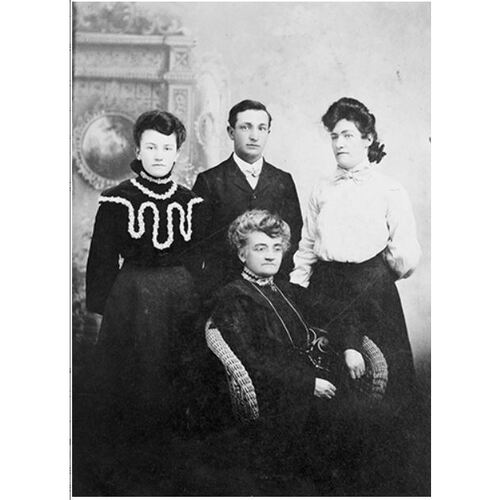

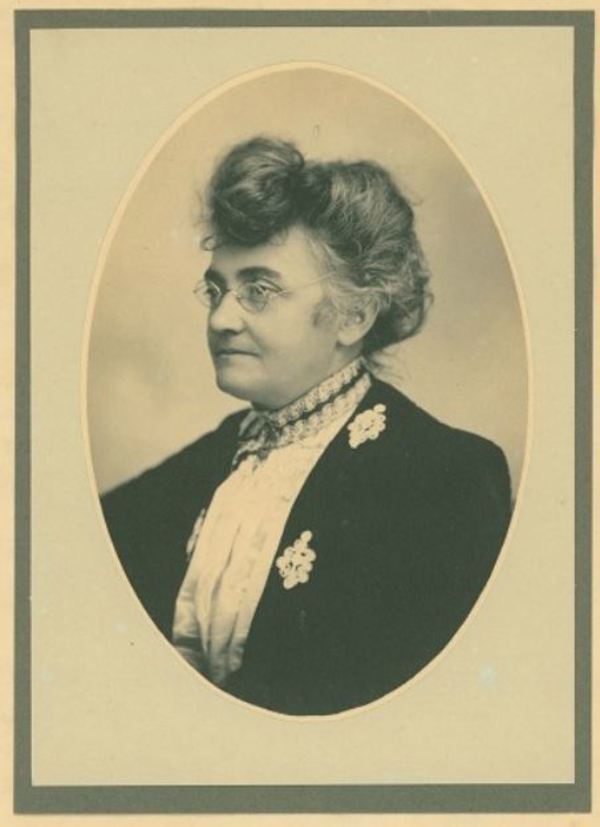

THOMPSON, GRACE SARAH HALL (Fletcher), businesswoman and social reformer; b. c. 1850, probably in Brock Township, Upper Canada, eldest of the 14 children of Joseph Thompson, a farmer, and his wife Elizabeth, a Scots immigrant whose surname may have been Hall; m. Joseph Fletcher, and they had two sons and two daughters who survived infancy; d. 3 Aug. 1907 in Saskatoon, Sask.

By 1879 Grace Thompson and Joseph Fletcher were married and living in Alliston, Ont. In the spring of 1884 Joseph went to the North-West Territories to take up a homestead on the lands recently granted to the Toronto-based Temperance Colonization Society by the government. Grace and their three children followed the next year. When they arrived in Saskatoon, the main settlement, they found a struggling community of about 100 people. Inexperienced at dry-land farming, the colony’s homesteaders had many failures, and until a rail link was established in 1890 their few products could not be shipped out. The Fletchers were so short of money in the fall of 1885 that after they bought their winter supplies they could not cash a friend’s $20 cheque.

Grace Fletcher became a general merchant in either 1887, the year that her younger daughter Nina was born, or 1888. It would appear that her store was in their home or adjacent to it, so that she would have been able to take care of her young family as well. Until 1890 retail goods had to be brought over the long, muddy trail from Moose Jaw or traded from the Prince Albert area. Grace went out of the settlement on trading trips and, since Joseph “did nothing” (as her brother-in-law affirmed) during the six months of the year when he was in town, she likely had to find others to care for the children when she was away. She also gave birth to another son, who died in infancy.

An ambitious entrepreneur, Grace Fletcher was an exceptional woman in the little settlement. For three years after the railway arrived, she and other dealers bought up the buffalo bones that littered the prairies and shipped them out to be made into fertilizer. The scanty records of her business ventures show that she made enough money as a merchant, bone dealer, and owner of a livery stable that she was able to begin buying real estate. The Saskatoon economy improved, and by 1905 the population had grown to 3,011. Three railways brought increasing numbers of settlers to the town, where they applied for homesteads. They purchased equipment, supplies, and livestock before they headed out to their land, and often returned for more. By 1906–7 Fletcher was a wealthy woman, owning property worth close to $70,000.

In 1886, at the first meeting of the official board of the Methodist church in Saskatoon, Fletcher had been appointed a Sunday-school teacher. She was “very active” in the church throughout her life and eventually bequeathed $10,100 to Methodist churches in Floral and Saskatoon. Unhappy with male domination of the church, she stipulated that the money was “to be put out in good security, the Church to use the interest each year after the women of the church get their full franchise in all church courts.” She also left $1,000 to the Saskatoon branch of the Woman’s Missionary Society. In 1910 Grace Church (now Grace Westminster United Church) was named in her honour.

Closely tied to Fletcher’s work in the church was her commitment to temperance. In the late 1880s, when the settlement was small and remote, the advocates of temperance were able to control alcohol, but when railway construction began, it became increasingly difficult to do so. In 1890 a hotel owner was charged with illegally selling liquor after Fletcher, who lived nearby, saw her husband and other men who had been drinking leave the premises. She had them sworn in as witnesses, and she produced as evidence a bottle she had taken from Joseph. He claimed he had bought it previously to make horse liniment, an excuse that was not accepted by the court.

It would appear that Joseph was an alcoholic and not very productive. Like many women who knew the tragedies caused by drunkenness, Grace joined the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, and she would bequeath the Saskatoon branch $2,500 “to pay a good speaker to visit our unions and lecture or speak on Temperance, and work for our Woman’s full franchise in all Local and Dominion elections.” Like the women’s missionary societies, the WCTU was important in the growth of the women’s movement. In Saskatchewan Fletcher was a forerunner of the feminists who after 1910 were to campaign successfully for the vote and to push through many improvements in laws concerning women and children.

Early in 1905 she and several other Saskatoon women presented a petition to the town council asking that it urge the territorial legislature to grant propertied women the franchise. She entreated all “whole souled liberal then” to help “give us the ballot and see how we will rush up and be a power in the land and we will not only train our sons to vote for the right but we will be better companions to our husbands.” She believed that the vote for women would be “British Fair Play” and would mean “better men in office and a cleaner and purer government.”

The question of married women’s rights to property was understandably important to Fletcher. A woman had no legal entitlement to a share in the homestead, which her husband could squander away. She wrote on the subject to the Saskatoon Phenix. “Think of it,” she exhorted the readers, “the wife and mother can be left destitute. Our legislature spends days regulating laws for prairie chicken; you look in vain for one word to protect the wife and mother.”

Fletcher’s sense of fair play was different, however, when it came to the question of separate schools. The Autonomy Bills, placed before the House of Commons in February 1905 by Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, were to create the new provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, and they were the subject of hot debate in the commons and in the country. Fletcher was a Conservative, and she was prejudiced against Catholics, “halfbreeds,” and Canadians who were not of British descent. She opposed Laurier’s attempt to entrench the right to separate schools in the bills.

Her children grown, Fletcher left for a holiday in Ontario in December 1906. While she was there her health began to fail and it continued to decline after she returned. She added two codicils to her will on her deathbed and died in August 1907. Her husband died two months later. The probate files show not only what was important to Grace, but also the split in the family over the question of drink. She bequeathed no money to Joseph, although she did leave him the use of a large home as long as her sister Allie and daughter Nina kept house there. To her son William Kirkland, who sided with his father, she left very little. Most of her estate went to her other three children and to Allie. Nina, who was single, was to get her share only if she did not marry “a drunkard.”

Additional documentation on Grace Thompson (Fletcher) appears in the author’s unpublished paper, “Businesswoman Grace Fletcher, temperance, women’s rights, and ‘British Fair Play’ in Saskatoon, 1885 to 1907” (Univ. of Sask., Saskatoon, in progress); a 1992 typescript copy is available in the DCB’s file on the subject.

Sask., Surrogate Court (Saskatoon), Probate files, G. H. [Thompson] Fletcher; Joseph Fletcher. Saskatchewan Arch. Board (Saskatoon), Homestead files, 31735, 31737, 169112, 200085, 734686; S-A359 (Trounce family papers). Saskatoon Public Library, Local Hist. Room, Pamphlet files, Churches, Grace 2, LH 7459 (“The history of Grace United Church, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan – Women’s Missionary Society, for the years 1900 to 1961”); Saskatoon hist. 6, LH 8760 (Eric Knowles, “Early days in Saskatoon”). Univ. of Sask. Library (Saskatoon), Morton

Cite This Article

Georgina M. Taylor, “THOMPSON, GRACE SARAH HALL (Fletcher),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thompson_grace_sarah_hall_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thompson_grace_sarah_hall_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Georgina M. Taylor |

| Title of Article: | THOMPSON, GRACE SARAH HALL (Fletcher) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |