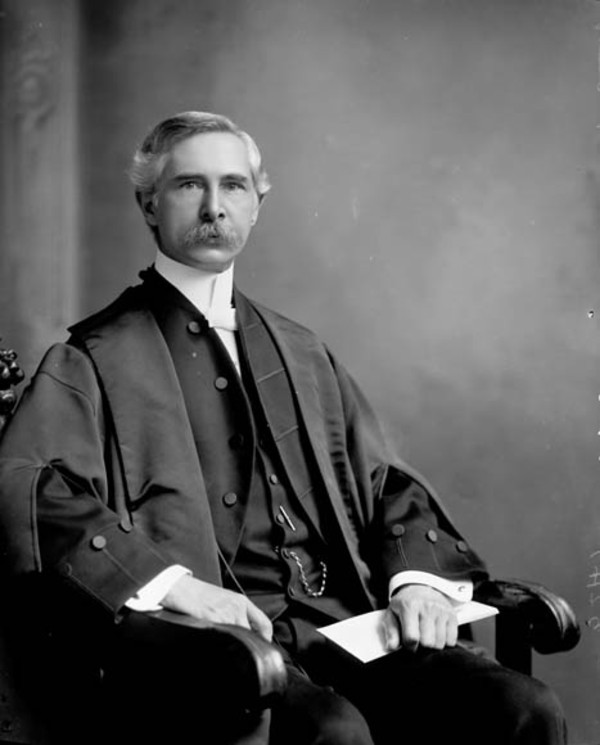

SUTHERLAND, ROBERT FRANKLIN, lawyer, politician, and judge; b. 5 April 1859 in Newmarket, Upper Canada, son of Donald Sutherland, a storekeeper, and Jane Boddy; m. 4 Sept. 1888 Mary Bartlet in Windsor, Ont., and they had two daughters; d. 23 May 1922 in Toronto.

Of Scottish-Irish parentage, Robert F. Sutherland moved to Windsor when he was 14 and resided with his sister, wife of the pastor of St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church. He studied at the Western University of London and the University of Toronto, and was called to the Ontario bar in Easter term 1886, in which year he became a member of the law firm of Cameron and Cleary in Windsor. Appointed a qc in 1898, by 1905 he would be the senior member of Sutherland, Kenning, and Cleary. Besides conducting an extensive court practice, he was active on the city council, the library board, and the cricket field. In his spare time, perhaps with an eye to broader political involvement, he learned to speak French.

When Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier* visited Windsor on his electoral campaign tour of 1900, the first speaker to welcome him was Sutherland. Only ten days before, he had received the Liberal nomination for Essex North, which had been held by the Liberals since 1891 and which included Windsor, the adjoining border towns, and the rural, mostly French Catholic north half of the county. In addition to lauding Laurier, Sutherland emphasized that, if elected, he would respect all creeds and nationalities. This impartiality became especially important as the campaign wore on. His opponents tarred him with being anti-Catholic and a one-time member of the Protestant Protective Association. He angrily responded that, though a Presbyterian, he had always acted with fairness towards Catholics. While a member of Windsor’s council and chairman of its finance committee, he had recommended that the Catholic hospital, the Hôtel Dieu, be excused from paying water rates. For this stand he had been condemned, in his words, as “a half Catholic and a poor Protestant.” He further maintained that his refusal to join the PPA had once cost him the mayoralty. Though the association was now defunct, he had reason to worry about the charges against him: in 1900 French-speaking Catholics could sway the election. In the end he easily defeated Solomon White*. His success, and that of Mahlon K. Cowan in Essex South, confirmed that the Liberals, as a coalition of urban Protestants and rural Catholics, could form an enduring political structure in Essex County.

One of the least voluble members of Laurier’s government, Sutherland worked diligently to build up his local support. He consulted with Laurier on regional appointments to the Senate. In 1905 he asked the prime minister to back the local bid to have the United States Steel Corporation build a massive plant near Windsor, but Laurier responded that no favouritism could be shown to a particular manufacturer. In parliament Sutherland had the Railway Act amended in 1903 to require railways to drain their properties – a concern in low-lying Essex – and to mount “suitable” cattle guards. His amendments also removed the legal defences used by railways to avoid claims and made them liable for cattle killed by trains. Though he gained popularity among farmers, he did not inspire urban voters. In his only lengthy speech in the House of Commons, in 1902, he had praised the “incidental protection” provided by the government’s tariff policies, which, he claimed, were responsible for the industrial growth of the Windsor area. Voters there were not impressed. In the election of November 1904 he lost the city but was re-elected thanks to his rural support.

When the commons convened in January 1905 Sutherland was named speaker. Though his accomplishments were slight, the Windsor Evening Record believed “his parliamentary experience brought him many friends and few enemies.” Moreover, he kept his local contacts strong. In August, for instance, he advised Windsor’s council that the Detroit–Windsor ferry was attempting to renew its licence on terms that favoured the service. Duly warned, the municipality petitioned Ottawa to make sure that the company paid a fee and lowered its rates. After his re-election in 1908, Sutherland declined another term as speaker. On 21 Oct. 1909 he was appointed a puisne judge in the High Court division of the Supreme Court of Ontario.

Sutherland’s largely undistinguished career on the bench was punctuated by occasional speaking engagements and cases that attracted mild attention. In 1919, in a referral that hinged on the definition of “public place,” he upheld a Toronto magistrate’s decision, under the War Measures Act, to fine a workman who had said of the war effort that “the British Parliament was bleeding Canada dry; that King George was just as bad as the Kaiser.”

In 1917 the quiet judge had been drawn into the complex, and very political, field of hydroelectric regulation, as a member of the commission set up to determine the amount and price of power to be supplied by the Electrical Development Company of Ontario Limited to the provincial Hydro-Electric Power Commission. The formation of a government by the United Farmers of Ontario in 1919 set the stage for confrontation between Premier Ernest Charles Drury* and the dynamic chairman of Hydro, Sir Adam Beck, over responsibility for the extravagant escalations in its funding and works. To consume its surplus power, it had been planning a system of hydroelectric radial railways. In an effort to neutralize Beck’s pressure, in July 1920 Drury appointed a royal commission under Sutherland’s chairmanship to examine the project’s feasibility.

A year later, in a majority report based on American experience and post-war financial conditions in Ontario, the commission came down against hydro-radials, which, it concluded, would require continual government funding. Moreover, they would compete with the publicly owned Canadian National Railways, their cost could not be justified until an expensive power station at Queenston had been completed and proved to be self-supporting, and with motor vehicles on the rise the government had already embarked on a major road-building program. The commission therefore opposed any provincial guarantees for municipalities seeking to finance hydro-radials. Drury was predictably pleased, but radial advocates in urban centres were incensed. Though the report recommended a municipally controlled system for Toronto, neither its mayor, Thomas Langton Church*, nor York County warden Len Wallace was appeased. Church lambasted Sutherland’s commission as a “frame-up.”

In May 1922, nine months after rendering this controversial report, Sutherland died at his home on Chestnut Park Road in Toronto. His commission’s findings, however, continued to receive scrutiny as the radial issue played itself out. A last-ditch scheme devised by Beck for joint control in Toronto was defeated in the municipal election of January 1923. The following year a second commission appointed by Drury to curb Hydro, headed by Walter Dymond Gregory, substantiated Sutherland’s conclusions. Later experience proved that hydro-radials would have been an economic disaster. Even one of their supporters, William Rothwell Plewman, a Toronto alderman, eventually conceded that Sutherland’s commission had been right.

AO, RG 3-5-0-26, 3-5-0-28; RG 22-305, no.45416; RG 80-5-0-158, no.3524. City of Windsor Municipal Arch. (Windsor, Ont.), RG 2, AIV 1/8 (City Council minutes), 14 Aug. 1905. LAC, MG 26, G, Sutherland to Laurier, 26 July 1905; Laurier to Sutherland, 28 July 1905. Border Cities Star (Windsor), 24 May 1922. Evening Record (Windsor), 20 Oct., 3, 8 Nov. 1900; 26 Oct. 1904; 7 Jan. 1905; 28 Oct. 1909. Globe, 17 July 1920, 13 Aug. 1921, 24 May 1922. Can., House of Commons, Debates, 25 March 1902, 11 Jan. 1905. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). CPG, 1905. Encyclopaedia of Canadian biography . . . , vol.3. C. M. Johnston, E. C. Drury: agrarian idealist (Toronto, 1986). The King v. Watson (1919), Ontario Weekly Notes (Toronto), 15: 417–18. Ont., Commission appointed to inquire into hydro-electric railways, Reports (Toronto, 1921); also issued in Ont., Legislature, Sessional papers, 1922, no.24. W. R. Plewman, Adam Beck and the Ontario Hydro (Toronto, 1947).

Cite This Article

Patrick Brode, “SUTHERLAND, ROBERT FRANKLIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sutherland_robert_franklin_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/sutherland_robert_franklin_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Patrick Brode |

| Title of Article: | SUTHERLAND, ROBERT FRANKLIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |