![Archives de la Bibliothèque publique juive. pr007500 [Détail] Original title: Archives de la Bibliothèque publique juive. pr007500 [Détail]](/bioimages/w600.24716.jpg)

Source: Link

ROTH, IDA (Steinberg) (the family used the surname Sternberg before their arrival in Canada in 1911), grocer and businesswoman; b. 26 Jan. 1883 in Balkány, Hungary, daughter of Hani Fogel (Fógel) and Zsigmond Roth (Róth); m. c. 1902 Vilmos (William) Sternberg (Steinberg) in Hungary, and they had six children; d. 4 April 1942 in Montreal and was buried there the next day.

From Hungary to Canada

Born to Jewish parents in Balkány, a village in northeastern Hungary, Ida Roth was the eldest daughter in a family of eight children and very modest means. Orphaned as a teenager, Ida was adopted by her uncle, and her siblings were taken in by various relatives. Ida worked in her uncle’s general store in a village near Debrecen, where she acquired small-business skills. In the early years of the 20th century (probably 1902), she wed Talmudic scholar Vilmos Sternberg, who worked sporadically as a baker. It appears to have been an arranged marriage; according to family legend, the young couple met for the first time the evening before their wedding.

Four of Ida Roth’s six children were born in Hungary: Jack (c. 1903), Samuel* (c. 1905), Nathan (c. 1908), and Lily (c. 1909). In 1911 Ida, Vilmos, and their four children left Hungary for Canada, presumably to better their economic situation. They sailed from Antwerp, Belgium, on the Montfort, one of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s “emigrant ships,” arriving in Quebec City on 17 June 1911. Listed as a baker in the ship’s registry, Vilmos told immigration officials that the young family was going to join his brother-in-law, the owner of a delicatessen, in Montreal. It was in Quebec City that, owing to a clerk’s transcription error, the Sternbergs became Steinbergs. Once in Canada, Vilmos would use William as a given name. No doubt the young couple had chosen Montreal as a final destination because two of Ida’s sisters, Mary and Rachel, were already living there; her sister Fannie and her brother Lewis would arrive later.

Jewish Montreal in the early 20th century

Ida, William, and their children joined a rapidly growing community of Ashkenazi Jews in Montreal, then the metropolis of both Quebec and Canada. A small Jewish population had first established itself in Lower Canada in the late 18th century, becoming financially at ease and relatively well integrated into Quebec’s anglophone bourgeoisie. The last decades of the 19th century, however, and the turn of the 20th witnessed the arrival of thousands of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe (the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian empires, and Romania) who were fleeing poverty, antisemitism, and the Russian pogroms. Between 1901 and 1911 the Jewish population of Montreal rose from 7,000 to 28,000. Most of the newly arrived settled in Montreal’s immigrant neighbourhoods, which were concentrated around Boulevard Saint-Laurent, known colloquially as “the Main,” extending from the port all the way north past Avenue du Mont-Royal. By 1931 over half the residents of the Saint-Louis and Laurier wards, both centred on Boulevard Saint-Laurent, were Jewish. Many of the men, unmarried women, and adolescents in these districts worked in the clothing industry (known in Yiddish as the schmata, or “rag,” trade) [see Lyon Cohen*] as tailors, seamstresses, and machine operatives, among other occupations. Ida’s sister Mary, for instance, worked in a garment factory. Other Jewish immigrants in Montreal opened small businesses – groceries, butcher shops, or dry-goods stores – on or around the Main.

Separation

Upon their arrival in the city, Ida and her family lived with her sisters Mary and Rachel in a large old house near the port. Like many married, working-class women in Montreal, they took in boarders as a source of income. Although a baker by trade, William had difficulty finding work, and money was scarce. Two more sons were born to Ida and William soon after their arrival in Canada: Max (c. 1912) and Morris (c. 1915). Shortly after the birth of Morris, Ida and William separated. One history of the Steinberg family claims that Ida’s sisters had encouraged this separation as a way of preventing any new births. William had difficulty fulfilling his expected role as breadwinner and meeting the material needs of his family; any additional children would have constituted a considerable financial burden.

After the separation, Ida and her six children resided with Mary and Mary’s son, Sam Cohen. William lived on Rue Cadieux (Rue de Bullion) near Rue de La Gauchetière, a downtown neighbourhood that was predominantly Jewish. He was listed in the 1915–16 city directory as a watchman. Ida’s daughter Lily corresponded with her father after her parents’ separation. Her surviving letters, written between the ages of nine and eleven and signed “Your Loving Daughter” or “Your dear little daughter Lily Steinberg,” are warm and affectionate. They are also concerned with practical matters: Lily requested money from her father for a violin as well as items of clothing (stockings and “underpance”) for herself and her brothers. She reported on her progress at school and on the health and activities of her mother and brothers, as well as the state of the family finances. In 1919 or 1920, during the recession that followed the First World War, Lily wrote that it was “very slack around here and is hard to make a living.”

Mrs. I. Steinberg, Grocer

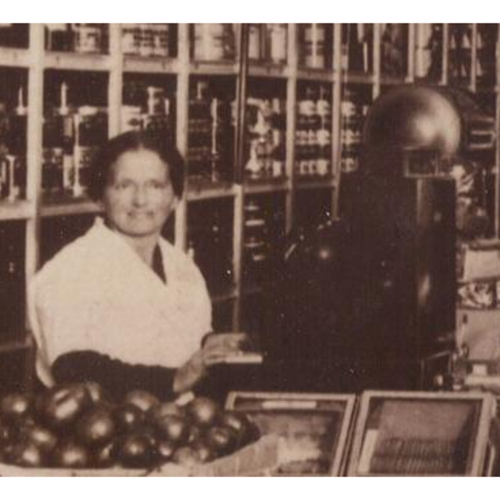

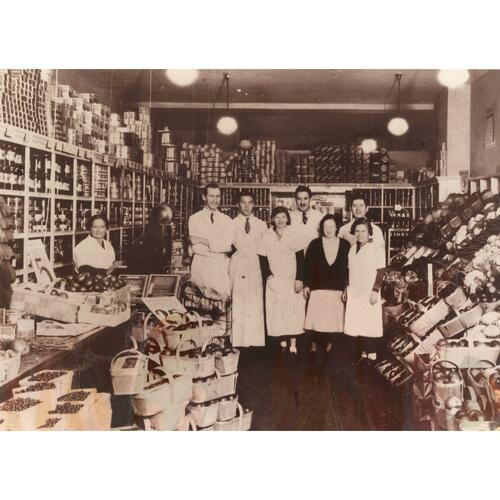

In January 1917 Ida opened a grocery store on the Main. The 1921–22 Montreal directory lists Ida as a widow (even though William was still alive) and her profession as “of the Main Delicatessen” at 1451 Boulevard Saint-Laurent, between Rue Marie-Anne and Avenue du Mont-Royal. Ida and her family lived behind and above the shop. By 1925 she had rented the space next door and expanded the store. Jewish immigrants to Canada at the turn of the 20th century frequently founded small businesses, like grocery stores, that required relatively little start-up capital; Ida’s initial investment in merchandise amounted to $200. Such shops relied on local markets; over time their owners built close relationships with customers from the neighbourhood, often providing credit to regular clients to secure their loyalty. Ida Steinberg worked tirelessly, from dawn until well past dusk, six days a week, in order to provide quality products and service to her customers. She endeavoured to offer the lowest prices possible by selling large volumes of goods. A photograph taken in her store in the 1920s shows her, tiny and trim, behind the cash register, with four young men and three young women, some of them likely her children, posing for the camera. The shop is piled high with baskets of fresh produce, tinned goods, and glass cases of biscuits. Local customers telephoned in their orders, which were subsequently delivered to their home in a horse-drawn cart. While Ida no doubt spoke Yiddish and Hungarian before her arrival in Canada, her children were sent to English-language schools run by the Protestant Board of School Commissioners of the City of Montreal [see Maxwell Goldstein*], and it is likely that Ida communicated with her customers and suppliers in Yiddish, but also in English and perhaps French. All six of Ida’s children worked in the shop, which allowed Ida to keep an eye on them while running the family business. This juvenile labour was essential to its survival. Five of the six children sacrificed their schooling in order to contribute to the family economy; only Max completed high school. In an interview conducted decades later, Lily remembered crying her eyes out upon being told that she had to leave school, a mere year before her high school graduation, because she was needed at the store.

In the 1920s Ida’s second son, Samuel, had begun opening new branches of the grocery, initially on Bernard Avenue in Outremont (Montreal). The business was incorporated in 1930 as Steinberg’s Service Stores Limited; Samuel and his wife, Helen, had controlling interest while other family members held the remaining shares. During the difficult years of the Great Depression, Samuel introduced new self-serve, or cash-and-carry, stores [see Theodore Pringle Loblaw*; William James Pentland*] called Steinberg’s Wholesale Groceterias, allowing him to slash prices by about 15 to 20 per cent. By 1934 there were 11 Steinberg stores in various parts of Montreal. Le Devoir (20 Nov. 1934) reported that the company had 56 employees and a capital of about $32,000 that year, and that it had made a profit of about $22,000 in the 1931–32 fiscal year. According to author Aline Gubbay, one former resident of the neighbourhood around the Main remembered: “Near the corner of Mount Royal was Mrs. Steinberg’s grocery store. It was big, bigger than the others. When they moved away and grew to be a chain store, Mrs. Steinberg said they shouldn’t open [a wholesale location] on the Main. It wasn’t suitable. The Main was for small family businesses.” The cash-and-carry model was so successful that all the stores were converted, and by 1937 the company itself had been officially renamed Steinberg’s Wholesale Groceterias Limited.

In 1931, in an attempt to lighten his mother’s workload, Samuel had shut down her still-bustling grocery store on Boulevard Saint-Laurent. At that point, Ida became the co-manager, with daughter Lily, of the Steinberg’s store on Avenue de Monkland in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, a middle-class Montreal neighbourhood whose residents were largely English-speaking. Ida and Lily shared an apartment above the store at 5667 Avenue de Monkland until 1936. In a society wedding held in June 1939, Lily married Hyman Rafman, the son of a tailor and himself a manufacturer and the proprietor of Washmor Frocks. Lily’s active role in the Steinberg business appears to have ended shortly thereafter.

Last years

Throughout the 1930s, Ida maintained close relationships with her six children and their spouses. Lily and her five brothers sent their mother postcards when they travelled, enquired about her health, and urged her not to work too hard. When in town, they organized family dinners and took their mother to shows at the Montreal chapter of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association.

In 1942, the year of Ida’s death, the Montreal directory listed 23 branches of Steinberg’s Wholesale Groceterias in various neighbourhoods and suburbs, including Westmount and Verdun (Montreal), in addition to the head office and warehouse on Avenue Overdale. All five of Ida’s sons – Jack, Sam, Nathan, Max, and Morris – were listed as working for the company in various capacities (manager of the maintenance office, president, secretary-treasurer, superintendent, and cashier, respectively). The largely Yiddish-speaking clientele that had frequented Ida’s store in the late 1910s and 1920s grew into a city-wide customer base, both English- and French-speaking. In fact, the phrase “faire son Steinberg” became part of francophone Montrealers’ vocabulary as a synonym for doing one’s grocery shopping. Ida’s portrait hung in Steinberg’s Montreal boardroom in recognition of her role as the founder of the business.

Ida Steinberg died of a heart attack on 4 April 1942, midway through the Second World War, at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital. She was 59 years old. Her funeral took place at Paperman and Sons funeral parlour on Rue Saint-Urbain, just a few blocks from the site of the grocery she had founded in 1917. Hundreds of friends, family members, and former customers and suppliers were in attendance. She is buried in Montreal’s Back River Memorial Gardens Cemetery in the Hungarian Hebrew section. Her estranged husband, William, who outlived her by five years, is buried two rows away.

The enterprise Ida had founded continued to grow for decades after her death under the leadership of her son Sam. It was sold and dismantled in 1989, and the last Steinberg’s stores closed on 5 Sept. 1992. Three years later a small street in an industrial district in Montreal’s Viauville neighbourhood was named in Ida’s honour.

Ancestry.com, “Canada, incoming passenger lists, 1865–1935,” Ida Sternberg [Steinberg], 17 June 1911: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1263; “JewishGen online worldwide burial registry,” Ida Steinberg, Montreal, 5 April 1942: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1411; “Quebec, Canada, vital and church records (Drouin coll.), 1621–1968,” Ida Steinberg, Outremont [Montreal], 4 April 1942: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1091/ (records consulted 26 Feb. 2024). FamilySearch, “Hungary, Civil registration, 1895–1980,” Hani Fógel, Nyírmihálydi, 5 May 1899: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KZQT-R1R?cid=fs_copy; Zsigmond Róth, Nyírmihálydi, 17 June 1899: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KZQT-K68?cid=fs_copy; “Hungary, Jewish vital records index, 1800–1945,” Ida Roth, Balkány, 26 Jan. 1883: www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q2S1-XRP5?cid=fs_copy (records consulted 26 Feb. 2024). Find a Grave, “Memorial no.103801712”: www.findagrave.com (consulted 11 Aug. 2020). Jewish Public Library, Arch. (Montreal), Fonds 1066 (Steinberg/Rafman family fonds). Library and Arch. Can. (Ottawa), R233-114-9, Que., dist. Georges-Étienne Cartier (166), subdist. St Jean Baptiste Ward (30): 7. “Décès de Mme Ida Steinberg,” La Patrie (Montréal), 6 avril 1942: 9. “Feu Mme I. Steinberg,” La Presse (Montréal), 6 avril 1942: 9. “Now what would mother have done? Answer leads to billion dollar chain of stores,” Windsor Star (Windsor, Ont.), 31 Dec. 1959: 17. “Les ‘Thrift Stores,’” Le Devoir (Montréal), 20 nov. 1934: 3. Pierre Anctil, Histoire des Juifs du Québec (Montréal, 2017). Directory, Montreal, 1914–42. Ann Gibbon and Peter Hadekel, Steinberg: the breakup of a family empire (Toronto, 1990). Aline Gubbay, A street called the Main: the story of Montreal’s Boulevard Saint-Laurent ([Montreal], 1989). Radio-Canada, “Il y a 25 ans, Steinberg disparaissait”: ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1053976/steinberg-supermarche-commerce-alimentation-histoire-archives (consulted 29 May 2023). Louis Rosenberg, Canada’s Jews: a social and economic study of Jews in Canada in the 1930s, ed. Morton Weinfeld (Montreal, 1993). Sylvie Taschereau, “L’arme favorite de l’épicier indépendant: éléments d’une histoire sociale du crédit (Montréal, 1920–1940),” Canadian Hist. Assoc., Journal (Ottawa), 4 (1993), no.1: 265–92.

Cite This Article

Magda Fahrni, “ROTH, IDA (Steinberg),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/roth_ida_17E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/roth_ida_17E.html |

| Author of Article: | Magda Fahrni |

| Title of Article: | ROTH, IDA (Steinberg) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 17 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2024 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |