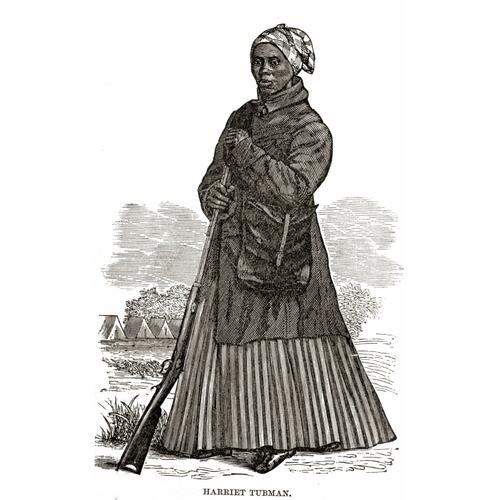

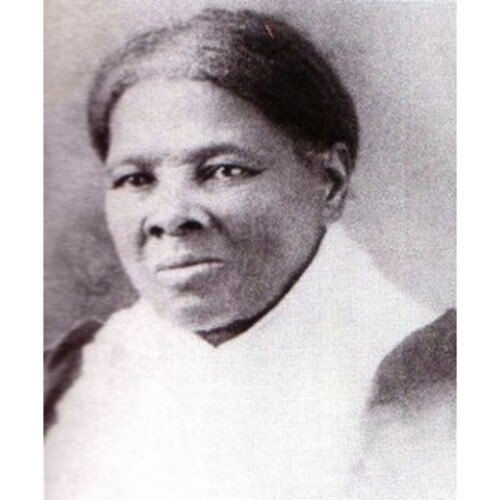

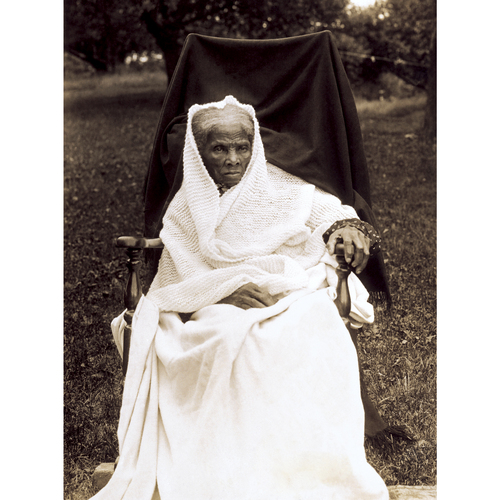

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ROSS, HARRIET (originally named Araminta) (Tubman; Davis), also known as Moses, fugitive slave and “conductor” on the Underground Railroad; b. 1820 or 1821 near Bucktown, Dorchester County, Md; m. first c. 1844 John Tubman (d. 1867); m. secondly 1869 Nelson Davis (d. 1888); she had no children; d. 10 March 1913 in Auburn, N.Y.

Araminta Ross was born on a large plantation in Maryland. One of the 11 children of Benjamin Ross and Harriet Greene, both slaves, she began to use her mother’s Christian name at an early age. As a child, she toiled as a field-hand, doing tasks that demanded strength and endurance. Ross experienced many of the cruelties that were inherent in the American slave system. When she was about 13, she was struck in the head by a weight hurled by an overseer; the resulting injury would cause seizures and bouts of somnolence for the rest of her life. In 1844 she married a free black, John Tubman, and she would retain Tubman as her surname after her second marriage. Fearing that she would be sold to the Deep South after the death of her master, Tubman escaped in 1849 without her husband and headed north to Philadelphia. There she worked as a cook in hotels and clubs to finance her clandestine excursions to liberate other slaves via the Underground Railroad, a loosely organized network of safe houses and people who helped fugitives pass from the slave states to free states in the north. Tubman first returned to the slave states in 1850 to rescue her sister Mary Ann Bowley of Baltimore and Bowley’s two children.

Blessed with great physical stamina, a mind for logistics, and an ability to lead through the use of flattery and intimidation, she was perfectly suited to this type of work. At first she left her charges in the states of Delaware and New York and in Philadelphia. However, the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 vastly increased the ability of slave-owners to pursue escapees. Since northern states could no longer offer freedom-seekers the same degree of protection, Tubman began to bring them across the border to Upper Canada at Niagara Falls. From there they travelled to nearby St Catharines, where they were aided by the Reverend Hiram Wilson, an abolitionist and the leader of the local refugee community.

In the fall of 1851 Tubman moved to St Catharines, which would be the centre of her anti-slavery activities for the next seven years. A member of the interracial Refugee Slaves’ Friends Society, she became indispensable, not only in bringing escaped slaves to Canada but also in helping them adjust to freedom in a new country. After 1850 St Catharines quickly grew as a result of this influx, with 123 black families listed on the assessment rolls in 1855.

Between 1852 and 1857, the period when she regarded St Catharines as her home, Tubman made 11 trips into the United States to rescue fugitives. These trips were especially fraught with danger, chiefly because of the $40,000 reward posted by a group of slave-owners for her capture, dead or alive. In late 1857 she undertook what was probably her most venturous journey, the rescue of her elderly parents from Maryland. They spent the winter with her in St Catharines. She subsequently settled them on land in Auburn, N.Y., that she had purchased from William Henry Seward, a sympathetic senator and later Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state.

In St Catharines Tubman rented a boarding-house where she lodged some of the escaped slaves. In the spring of 1858 the famous American abolitionist John Brown stayed with her in St Catharines, though by then Auburn had become her permanent home. Tubman none the less continued to maintain a high profile in St Catharines society; she was there during the winter of 1860–61 and served on the executive committee of the newly formed Fugitive Aid Society of St Catharines in 1861. In addition, she continued to receive private funding from Canada, much of it conveyed to her in Auburn by the Reverend Michael Willis* of Toronto.

Tubman’s last visit to Maryland to lead out slaves occurred in December 1860. After the start of the Civil War, she channelled her energies toward aiding the Union cause. Armed with letters of introduction from some of Massachusetts’ most influential citizens, she took up residence near Beaufort, S.C., in 1862. From there she assisted the Union army for the next three years as a cook, nurse, spy, and scout. In 1868 Seward petitioned Congress for a military pension for Tubman. Although the petition was rejected, she did receive a pension in 1890, two years after the death of her second husband, who had served in the Union army.

Following the war Tubman returned to Auburn. She remained active until her death, raising money for such causes as the education of freed men and women in the south and the Harriet Tubman Home for Aged and Indigent Colored People in Auburn. Much of the profit from a biography of Tubman written by Sarah Elizabeth Hopkins Bradford in 1869 went toward these causes. Tubman died of pneumonia in 1913 at the age of 93. Never able to read or write and physically challenged, Harriet Tubman had still been able to put aside these difficulties and, over the course of 15 to 19 trips into the slave states, personally liberate up to 300 people. No other conductor on the Underground Railroad rivalled Tubman in the number of trips and the number of slaves liberated. Her life remains a testament to bravery, altruism, and human ingenuity.

Ontario Heritage Foundation (Toronto), Harriet Tubman file. St Catharines Hist. Museum (St Catharines, Ont.), Harriet Tubman file. L. W. Bertley, Canada and its people of African descent (Pierrefonds, Que., 1977). The black abolitionist papers, ed. C. P. Ripley (5v., Chapel Hill, N.C., 1985–92), 2. Linda Bramble, Black fugitive slaves in early Canada (St Catharines, 1988). W. A. Breyfogle, Make free; the story of the Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, 1958). Henrietta Buckmaster, Let my people go; the story of the Underground Railroad and the growth of the abolition movement (New York, 1941; repr. Columbia, S.C., 1992). Earl Conrad, Harriet Tubman (Washington, 1943; repr. New York, 1969). D. G. Hill, The freedom-seekers: blacks in early Canada (Agincourt [North York], Ont., 1981). S. [E.] H[opkins] Bradford, Scenes in the life of Harriet Tubman (Auburn, N.Y., 1869; repr. Freeport, N.Y., 1971). J. A. McGowan, Station master on the Underground Railroad: the life and letters of Thomas Garrett (Moylan, Pa, 1977). Notable American women, 1607–1950: a biographical dictionary, ed. E. T. James et al. (3v., Cambridge, Mass., 1971), 3: 481–83. Benjamin Quarles, “Harriet Tubman’s unlikely leadership,” in Black leaders of the nineteenth century, ed. L. [F.] Litwack and August Meier (Urbana, Ill., and Chicago, 1988), 43–57. R. W. Winks, The blacks in Canada: a history (Montreal, 1971).

Cite This Article

Owen Thomas, “ROSS, HARRIET (Araminta) (Tubman; Davis) (Moses),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 12, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_harriet_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ross_harriet_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Owen Thomas |

| Title of Article: | ROSS, HARRIET (Araminta) (Tubman; Davis) (Moses) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | March 12, 2026 |