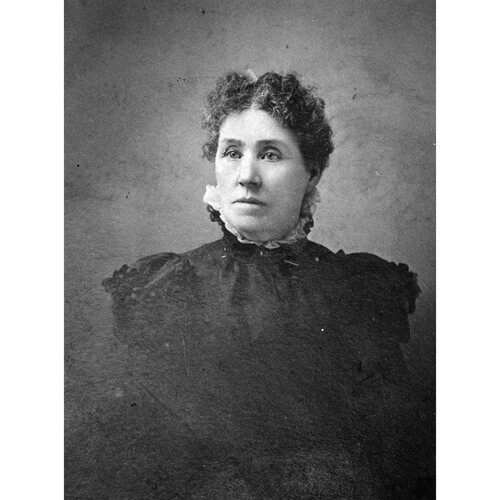

![Annie Rogers Butler [Lucy Anne Harrington Rogers (Butler)]. Image courtesy of Yarmouth County Museum and Archives. Original title: Annie Rogers Butler [Lucy Anne Harrington Rogers (Butler)]. Image courtesy of Yarmouth County Museum and Archives.](/bioimages/w600.13846.jpg)

Source: Link

ROGERS, LUCY ANNE HARRINGTON (Butler), diarist, teacher, and matron; b. 24 March 1841 in Yarmouth, N.S., eighth child of Benjamin Rogers and Elsie Knowles; m. there 9 June 1870 John Kendrick Butler, and they had a son and a daughter; d. 21 Jan. 1906 in Halifax.

There is little information about Annie Rogers’s childhood and early adult life, but we do know that she was raised in the strict discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist tradition and that she was well educated. Her father was a shipbuilder and at least one brother a sailor. In June 1870 Annie married John Kendrick Butler, a master mariner, in Providence Church, Yarmouth. She was 29 years old and John four years her senior. One month later they left for Boston; from there Annie accompanied her husband on a trading voyage to South America aboard the brig Daisy.

Despite the popular superstition that having women aboard brought bad luck, it was not uncommon for captains to have their wives and even their children accompany them on established trading routes. The captain served many functions, including acting as navigator, master seaman, and business agent for the owner, but an important duty involved his role as employer and manager of a labour force. In this capacity he was responsible not only for hiring and keeping workers, but also for imposing discipline. He was expected not to fraternize with the crew, and to socialize with the mates only if they were related by blood or marriage. Thus he was left with little companionship for extended periods of time. Without his family a captain often faced a lonely and isolated life.

When Annie agreed to accompany John on the Daisy for what was to be a honeymoon voyage, neither could have predicted the delays and the dangers they would encounter because of an epidemic of yellow fever raging in Buenos Aires. The trip would take more than 13 months. On 3 Jan. 1871, after 98 days at sea, Annie began a journal to record her observations, thoughts, and feelings during the remaining voyage. Ironically, it is this private document that has brought her to the attention of the public.

Annie’s diary provides a lively and vivid account of life on a small vessel, as experienced by the only woman on board. Despite the cramped quarters and the absence of other females, Annie established familiar domestic routines, busying herself with such chores as washing, ironing, sewing, mending, baking, preserving, and “house” cleaning. On 18 April, when her Yarmouth friends would have been engaged in spring cleaning, Annie was doing the same off Buenos Aires: “John has gone ashore and I am into housecleaning strong. I have got one of the men helping me. We have got everything cleared out of our room and I have got Tom white washing.” The perpetuation of domestic rhythms appears to have provided both purpose and comfort for Annie in an otherwise alien environment.

The journal illustrates the class differences that existed on a small ship. Although the crew were respectful and polite to her, she was unhappy when John went ashore and she was left “sad and lonely among a set of roughs.” Their coarse language and alcohol consumption were particular sources of stress to her, as was their failure to observe the sabbath. None the less she felt responsible for encouraging Christian values and practices among the men. She donated a Bible to them, prayed on their behalf, tended the sick, and offered comfort when they became “blue.”

Annie’s diary also reflects the close relationships that women shared as relatives and friends. She particularly missed her sister Maria (“Rie”) and often dreamt of her. Letters from the family and friends on the one hand brought eagerly awaited news, but on the other served as a reminder of Annie’s deeply felt longing for “home, sweet home.” She had the occasional opportunity to socialize with the wives of other captains off Buenos Aires, and these brief encounters were a source of pleasure. The deep affection that she and John shared could not quench her desire for female companionship.

By March 1872 Annie had settled into her own home in Yarmouth. She would never again accompany her husband to sea. In April a son, Frank, was born, and three years later she gave birth to her daughter, Elsie. In December 1876 John left on the brigantine Clarence bound for Martinique. The ship was lost at sea. At 35 Annie was left a widow with two small children.

Not a great deal is known of her life for the next 15 years. She remained in close contact with John’s parents, living with or near them and caring for them until their deaths. She began a small nursery school or kindergarten in May 1882. Initially nine children attended, six of whom were Butler and Rogers relatives. Her records indicate that her fee was 25 cents a week.

In 1891, with her two children, Annie left Yarmouth for Halifax to take up the position of matron of the Protestant Orphans’ Home. The orphanage was a charitable institution that admitted Protestant children from two years of age upwards, and it enjoyed considerable financial support. Independent charitable institutions provided women like Annie, who were well educated and self-supporting, with some career options. Like the deaconesses, matrons, and teachers at the Jost Mission in Halifax, an institution founded to serve the city’s poor, Annie belonged to a group of paid female workers whose responsibilities included administering charitable programs for working-class women and children. They were the predecessors of women who would later enter the profession of social work. Their activity reflected the Christian concern for those who were poor or disadvantaged. It also reinforced the prevailing doctrine of separate spheres, according to which it was women’s responsibility to care for their “poorer sisters” and their children.

After her retirement in 1900, Annie Butler lived with her two children in a house very close to the orphanage. She remained there until her death in 1906. Her story is not unlike that of many other educated, middle-class women living in coastal communities in Nova Scotia during the second half of the 19th century. Seafaring activities played a central role in their lives, often with tragic consequences. Like many of her Nova Scotian sisters, Annie was able to survive through close family ties, a strong religious faith, and female resourcefulness in putting her education to practical and monetary use.

[Biographical details concerning Lucy Anne Harrington Rogers (Butler) were kindly supplied by Mr Raymond Simpson, a grandson, from private papers in his possession. These include the original Annie Butler diary, a microfilm copy of which is at the PANS, as well as letters and other documents which are not available elsewhere, and form the basis of his manuscript, “If we are spared to each other: love and faith against the sea.”

Excerpts from Mrs Butler’s diary appear in an anthology co-edited by the author, No place like home: diaries and letters of Nova Scotia women, 1771–1938, ed. Margaret Conrad et al. (Halifax, 1988), which also reproduces a photograph of the subject held by the Yarmouth County Museum and Hist. Research Library (Yarmouth, N.S.). It should be noted that the surname of Annie’s parents is given incorrectly as Butler on p.135 of the first printing, but has been corrected in the second printing. t.a.l.]

Directory, Halifax, 1890/91. Judith Fingard, Jack in port: sailortowns of eastern Canada (Toronto, 1982). E. W. Sager, Seafaring labour: the merchant marine of Atlantic Canada, 1820–1914 (Kingston, Ont., 1989). Christina Simmons, “‘Helping the poorer sisters’: the women of the Jost Mission, Halifax, 1905–1945,” Acadiensis (Fredericton), 14 (1984–85), no.1: 3–27. S. T. Spicer, Masters of sail: the era of square-rigged vessels in the Maritime provinces (Toronto, 1968).

Cite This Article

Toni Ann Laidlaw, “ROGERS, LUCY ANNE HARRINGTON (Butler),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_lucy_anne_harrington_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_lucy_anne_harrington_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Toni Ann Laidlaw |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, LUCY ANNE HARRINGTON (Butler) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |