Source: Link

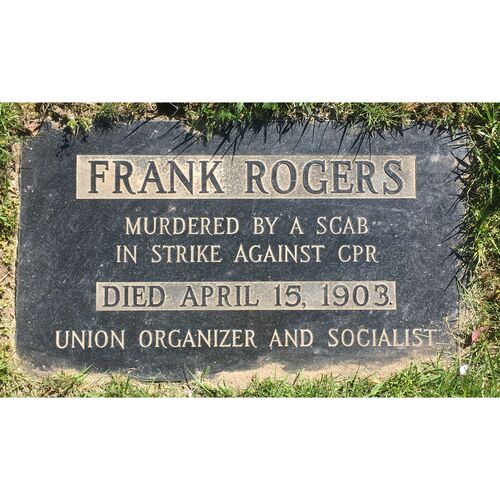

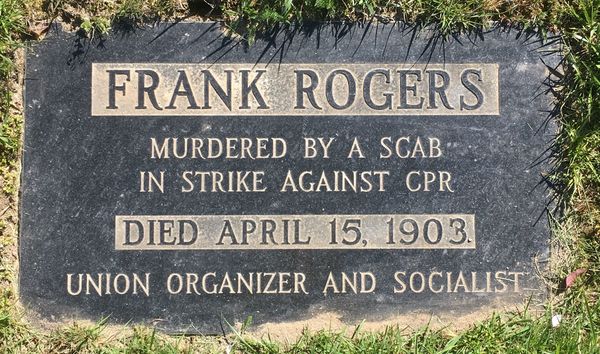

ROGERS, FRANK, political activist and union organizer; b. c. 1878; was married and had a family; d. 15 April 1903 in Vancouver.

By 1899 Frank Rogers was a leader in the factious left-wing community of Vancouver. He belonged to the first socialist group formed in the city, a local of the Socialist Labor Party established in 1898, but he left it in 1899 when it renounced unionism as essentially palliative. With Will MacLain, he subsequently formed a splinter club that became the United Socialist Labor Party in early 1900. Among its policies were a number of “immediate demands,” a concession to political reality that the SLP rejected as opportunism. In the provincial election that year the USLP fielded the first socialist candidate to run for public office in British Columbia, MacLain, and under Rogers’s guidance, it organized the first May Day celebrations in Vancouver.

Rogers also played a significant part in the city’s labour movement. He was a longshoreman and never worked in the fishing industry, but his most notable contribution to unionism was made through his vice-presidency of the fishermen’s union. Based in New Westminster and Vancouver, this body had been organized in late 1899 and early 1900. By the summer of 1900, when Rogers led an industry-wide strike, he was vice-president and was acknowledged to be the leader. The workforce was a multiracial one; about half the licences to fish on the Fraser were held by Japanese. Rogers attempted to unite the Japanese, natives, and Europeans who worked along the river, but bitter divisions between the groups remained. The central issues in the strike were recognition of the union and the establishment of a fixed price for sockeye salmon. Union boats patrolled the fishing grounds to discourage strikebreaking, and the Fraser River Canners’ Association regarded the patrols as intimidation. Once talks broke down, the association was able to have the militia called out. (The three justices of the peace who signed the requisition were a cannery owner, a former partner in a cannery, and a foreman at a cannery.) The day before the call-out Rogers had been arrested for intimidation, a charge which was withdrawn two days later. With substantial numbers of Japanese willing to work and the militia present to prevent demonstrations, the canners’ association was able to take a hard line with the union, which it never officially recognized. The strikers agreed to return to work in early August, having gained their demand for a uniform price. Although they had won less than total victory, Rogers’s popularity remained high. He was given an ovation and elected president of the union.

The sockeye season in 1901 was also disrupted by a strike, which was in many ways a reprise of 1900. Rogers again spoke for the union and ended up in jail, this time for his alleged role in kidnapping some Japanese and marooning them on Bowen Island. Although never convicted, he spent some four months in custody before being allowed bail. After the 1901 strike he played no further role in the union and by 1903 the organization itself seems to have collapsed.

Rogers’s connection with the labour movement continued, however. During the spring of 1903 clerical staff of the Canadian Pacific Railway went on strike. In Vancouver, a city already well established as a union stronghold, workers rallied to their cause. Longshoremen and others involved in transportation refused to handle CPR freight. Rogers, active in the stevedores’ union, soon became involved. On the night of 13 April he and several others went to investigate a gathering by the CPR tracks at the foot of Abbott Street. They were fired upon, and Rogers died of his wounds 36 hours later.

Many people concluded that a CPR strike-breaker or special constable was responsible for Rogers’s death, an inference that is supported by circumstantial evidence. The subsequent inquest, however, found that he had been murdered “by some person or persons unknown.” The police charged a non-union CPR employee, James MacGregor, but no substantive evidence was produced at the trial and he was freed. Rogers’s murder was used by socialists to support their claims about the class struggle and it undermined the efforts of moderate labour leaders [see Christopher Foley].

BCARS, GR 429, box 10, file 1114/03; GR 1327, no.46/03. NA, MG 26, G: 50142. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 19 April 1903. Independent (Vancouver), 18 April 1903. Vancouver Daily Province, 23 June, 23, 25 July 1900; 6–22 July, 3, 7, 12 Aug., 10 Sept., 5 Nov. 1901; 14–21 April 1903. Vancouver Daily World, 24–25 July 1900; 7 Aug., 8–31 Oct., 5 Nov. 1901; 14–22 April, 7 May 1903. Weekly News-Advertiser (Vancouver), 21 April 1903. B.C., Legislative Assembly, Journals, 1900: cxli–clxxix, esp. clxxv–clxxix; Sessional papers, 1900: 1005–13. R. A. Johnson, “No compromise – no political trading: the Marxian socialist tradition in British Columbia” (phd thesis, Univ. of B.C., Vancouver, 1975). Loosmore, “B.C. labor movement.” McCormack, Reformers, rebels, and revolutionaries. P. A. Phillips, No power greater: a century of labour in British Columbia (Vancouver, 1967). H. K. Ralston, “The 1900 strike of Fraser River sockeye salmon fishermen” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., 1965). Robin, Radical politics and Canadian labour. P. E. Roy, A white man’s province: British Columbia politicians and Chinese and Japanese immigrants, 1858–1914 (Vancouver, 1989). P. G. Silverman, “A history of the militia and defences of British Columbia, 1871–1914” (ma thesis, Univ. of B.C., 1956); “Military aid to civil power in British Columbia; the labor strikes at Wellington and Steveston, 1890, 1900,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly (Seattle, Wash.), 61 (1970): 156–61. J. H. Tuck, “The United Brotherhood of Railway Employees in western Canada, 1898–1905,” Labour, 11 (1983): 63–88. W. P. Ward, White Canada forever: popular attitudes and public policy towards Orientals in British Columbia (Montreal, 1978).

Cite This Article

Jeremy Mouat, “ROGERS, FRANK,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_frank_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rogers_frank_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jeremy Mouat |

| Title of Article: | ROGERS, FRANK |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |