Source: Link

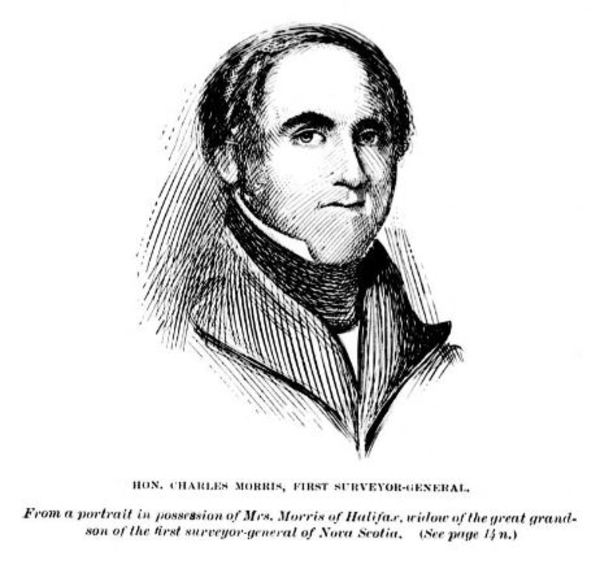

MORRIS, CHARLES, army officer, officeholder, and judge; b. 8 June 1711 in Boston, Massachusetts, eldest son of Charles Morris, a prosperous sailmaker, and Esther Rainsthorpe; m. c. 1731 Mary, daughter of John Read, attorney general of Massachusetts, and they had 11 children; buried 4 Nov. 1781 at Windsor, Nova Scotia.

In 1734 Charles Morris was teaching at the grammar school at Hopkinton, Massachusetts, and living with his wife on his late father’s farm, but his activities from then until 1746 are unknown. In that year he was commissioned captain by Governor William Shirley to raise a company of reinforcements for the defence of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia [see Paul Mascarene*]. On 5 Dec. 1746 Morris and 100 men were ordered to march from Annapolis Royal to the Minas region (near Wolfville) as the advance guard of Colonel Arthur Noble*’s detachment. Morris was present during the battle between Noble’s force and the Canadians and Indians under Nicolas-Antoine Coulon* de Villiers at Grand Pré on 31 Jan. 1746/47.

The New England reinforcements for Annapolis were ordered home to be disbanded in October 1747, but Morris and the other officers remained in service and spent the winter in Massachusetts recruiting for the Annapolis garrison. In October he had presented a memorial to Shirley stressing the need for a strong fort among the Acadians at Minas, and the governor evidently took this interest as a reason to send Morris to make a survey of the region. In the spring of 1748 Morris arrived at Annapolis; in May Mascarene, acting on Shirley’s orders, sent him to survey the Minas area and a month later ordered him to do the same in the Chignecto region. With 50 men, Morris traversed the Chignecto Isthmus, and he also surveyed the Bay of Fundy, at that time “Utterly unknown to the English.” During the course of the survey Morris collected from every Acadian district the number of inhabitants and the state of their settlements. Poor weather prevented him from carrying the survey along the north shore of the bay to Passamaquoddy Bay (N.B.). In February 1749 Shirley forwarded Morris’ “Draught of the Bay of Fundy” and his “observations taken upon the Spot” to the Duke of Bedford, secretary of state for the Southern Department, recommending that Morris be given further employment as a surveyor in Nova Scotia.

Morris’ observations, contained in a 107-page manuscript entitled “A breif survey of Nova Scotia,” led Andrew Hill Clark* to identify him as Nova Scotia’s first practical field geographer. The “survey” contains a “General Discription of Nova Scotia, its Natural Produce, Soil, Air, Winds etca,” identifies three climatic regions, and describes the Indians. It also includes an account of the trade, husbandry, settlements, and population of the Acadians and is an important source of information about them.

In “A breif survey” Morris had recommended that a strong fort be built on the Atlantic coast to offset Louisbourg, Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), and to protect British fisheries. When Halifax was founded by Cornwallis in 1749, Morris became one of its first settlers, and with the assistance of John Brewse laid out the town. On the recommendation of the Earl of Halifax, president of the Board of Trade, the governor appointed Morris “Chief Surveyor of Lands within this Province” on 25 September. In 1750 Cornwallis ordered Morris to survey the peninsula of Halifax and report on its acreage exclusive of the town and suburbs. Morris performed this task, suggesting that 240 acres be laid out as a common for firewood and later pasturage.

Morris must have been upset at how slowly the new British settlements of Halifax and Dartmouth progressed. In a report submitted in 1753 which analysed their slow rate of growth he described the new towns as garrison communities only and pointed out that many settlers, lacking employment, abandoned the colony as soon as they had expended the provision bounty. In his view, the settlements could not prosper until farmers and fishermen had migrated into the region.

In 1751 and 1752 Morris surveyed the coast from Port Rossignol (Liverpool) to the Chezzetcook region to examine possible sites for a new township which would house the “Foreign Protestants” then gathered at Halifax. Governor Peregrine Thomas Hopson* selected Mirligueche as the site because of its good harbour and at the end of April 1753 accompanied the expedition of Swiss and Germans to the region. From the first landing Morris and his assistant James Monk* Sr, with ten settlers to cut the brush, were busy laying out the new town of Lunenburg, and by 18 June he was staking individual lots. He also prepared a plan setting out the town and blockhouses and indicating existing clear land. During the summer Morris and his team laid out “garden lots” and made a tentative “Plan of Thirty Acre Farm Lotts continuous to the Town of Lunenburg,” which they presented to the Council on 15 September. The actual laying out of town lots went on until the summer of 1754. Since it was impossible to make complete surveys of hundreds of lots in the heavily wooded country around Lunenburg, the surveyors ran the baselines, established the corners, and blazed enough of the dividing lines to show their courses, leaving the settlers to continue them.

Morris was appointed to the Council on 30 Dec. 1755; he was therefore not a member when it was decided in July of that year to expel the Acadians. In 1751, however, he had already made the significant suggestion that the Acadians be rooted out of the Chignecto region in his “Representation of the relative state of French and English in Nova Scotia,” which he transmitted to Shirley, then leaving for England as one of the British commissioners empowered to settle the Anglo-French dispute over the boundaries of Acadia. Morris believed that the presence of the Indians and French on the north shore of the Bay of Fundy and at Chignecto made effective British settlement of the province impossible, and he recommended that the Acadians be removed “by some stratagem . . . the most effectual way is to destroy all these settlements by burning down all the houses, cutting the dykes, and destroys All the Grain now growing.” As the official most knowledgeable about the Acadians Morris was consulted by the Council during its deliberations on their fate. His opinions had not changed, and the Reverend Andrew Brown* found his report “little honourable to his heart . . . cruel advice and barbarous Counsel.”

Morris was among the councillors who complained to the Board of Trade in March 1757 about Governor Charles Lawrence*’s delay in calling a house of assembly; he favoured settlement of the province by New Englanders and knew that immigration would not occur unless prospective settlers were guaranteed an assembly. When the first legislature met on 2 Oct. 1758, Morris and Benjamin Green were the Council members who swore into office the first assembly representatives.

In the spring of 1759 the movement of New Englanders to the province was in its early stages, and on 18 April agents from Connecticut and Rhode Island appeared before the Council to discuss the lands being offered [see John Hicks]. It was agreed that Morris would accompany them on one of the province vessels and show them the “most convenient parts of the Country to settle Townships.” The Council having decided to make arrangements for a number of families to be settled at Minas, Rivière-aux-Canards (near Canard), Pisiquid (Windsor), and Grand Pré, it is apparent that Morris’ knowledge of the number of Acadian families which had been supported by each district must have been invaluable. Preliminary plans were made for townships at Chignecto and Cobequid (near Truro) as well, and on 17 August the Council, basing its decisions on a map of the province prepared by Morris, divided the province into five counties.

With the capture of Quebec, further arrangements were made in the spring of 1760 for the arrival of settlers from New England. On 8 May Morris was ordered to “proceed along the Coast Westward . . . to lay out and adjust the limitts of Townships.” During his voyage he visited the new town of Liverpool, where he left the inhabitants “in high spirits extremely well pleased with their Situation”; at Annapolis Royal he found 40 settlers, who had already formed a committee to lay out lots for Granville Township. At Pisiquid he discovered that the six transports which had arrived for Minas Township had “been out 21 days and suffered much for want of sufficient provender and Hay for their Stock.” He asked the Council for advice about whether to send the vessels back to New London (Conn.) for more settlers and about the location of settlements in the Pisiquid region, and he requested boards to construct shelter for troops and stores. The Council left all these problems to Morris’ judgement and ordered that he was to “have credit on the Treasury here or on Mr. [Thomas] Hancock in Boston for procuring lumber or paying labour as may be necessary.” Morris spent the summers of 1760 to 1762 looking after the new settlements, but he attended Council meetings in winter and proposed such practical measures as the procurement of various sorts of seeds, the appropriation of £25 to buy salt for the river fisheries at Horton, Cornwallis, and Falmouth, and a further allowance of pork and flour for the settlers of Liverpool.

The new townships were up to 100,000 acres in size, and “at [the time of] the first settlement” a “Town Plot was projected and laid out by the Chief Surveyor; and the boundaries of the Whole Tract fixt.” To cut and clear the lines in wilderness lands, Morris had the assistance of as many as 30 or 40 men, paid at public expense. Each township was granted in shares to a number of settlers ranging up to several hundred, and once the township boundaries were laid down, the divisions into the lots of land belonging to each settler were carried out by Morris’ appointed deputies, who were paid by the owners of the lots.

On 3 Nov. 1761 Administrator Jonathan Belcher forwarded to the Board of Trade three accurate maps prepared by Morris of places settled on Minas Basin, Cobequid Bay, and Chignecto. The following January Belcher transmitted Morris’ report of new settlements and his description of several towns. The 1761 report contains a good description of the natural resources of each township and their present and future use, and Morris’ shrewd observations and comments give a picture of Nova Scotia valuable to the government of the time and to historians, geographers, and environmentalists of today. Morris also described the New England migration and pointed out that during the summer the south coast had “a good Cod Fishery,” predicting that in a few years fishing would “be transferred from New England to this Coast.” He also claimed that a large trade in timber could be undertaken if the British government put a duty on Baltic timber equal to the cost of freight from Nova Scotia.

In the spring and summer of 1762 Morris was busy fixing settlers in the townships of Barrington, Yarmouth, and Liverpool and making a chart of the coast from Cape Sable to Cape Negro. The following year he and Henry Newton were sent to Annapolis County to investigate land disputes and to the Saint John River (N.B.) to inform the Acadians living near Sainte-Anne (Fredericton) that they were to move to another part of the province. They also told the New England settlers living at Maugerville that their lands were reserved for military settlement. Morris and Newton supported the New Englanders, however, by writing to Joshua Mauger, the provincial agent in London, asking him to use his influence with the Board of Trade to allow them to remain. The settlers were in fact later confirmed in possession of their lands. In the summer and autumn of 1764 Morris was sent to survey Cape Breton and St John’s (Prince Edward) islands and to inquire into the nature of the soil, rivers, and harbours, but poor weather confined his efforts to Cape Breton and Canso. The next year he surveyed Passamaquoddy Bay and the Saint John River, and in 1766 he surveyed the townships of Sunbury and Gage on the Saint John.

The large-scale speculation that was taking place at this period [see Alexander McNutt*] resulted in some extensive grants being made, and among these were concessions of 750,000 acres on the Saint John and grants covering all of St John’s Island. In 1768 Morris prepared a plan and description of the harbour of Saint John and the townships of Burton, Sunbury, Gage, and Conway, enclosing them in a letter to William Spry, one of the grantees on the river. In it he described the reversing falls, the intervales, the navigability of the river for vessels of 100 tons as far as Sainte-Anne, the spring flooding, and the yield of the region. He later recommended that at least 25 miles on each side of the river be reserved to the crown in order to provide pine timber as masts for the Royal Navy.

St John’s Island had been surveyed by Captain Samuel Jan Holland* in 1765–66, but no surveyor had laid out lots for prospective settlers. Accordingly, when Lieutenant Governor Michael Francklin drew up plans for the administration of the island in 1768, he ordered Morris to make further surveys. Morris was absent from May to October laying out “the ground on which the town of Charlotte Town” and other settlements were to be built. On his way home he was directed to inquire how “the lands in the Township of Truro, Onslow and Londonderry have been occupied.” In June 1769 Morris was instructed by Governor Lord William Campbell “to go from Hence to New York to settle the Limits and boundaries of the Governments of New York and the New Jerseys.” He was away for about a year completing this task, which appears to have been his last major surveying job, since he was never absent long enough from Council meetings thereafter to have undertaken other such work.

By the 1770s, inflation and the expense caused by new methods of granting land had made the salary and fees of the surveyor general’s office increasingly inadequate. By the new land instructions, a particular survey of each lot as well as the general survey of the whole tract had to be carried out at the expense of the surveyor general, “as no provision beforehand is made which was previously defrayed by govt or by grantees.” Morris’ son Charles* estimated in 1772 that from 1749 to 1771 his father had spent over £2,500 of his personal fortune on surveying expenses such as equipment and instruments which had not been paid by the government and, since the fees of the office averaged only £15 per annum, requested that a yearly increase be added from the parliamentary grant. The British government refused the request, but it agreed that Morris should be paid a certain sum for each 100 acres surveyed, the rate being left to the governor’s discretion. Governor Francis Legge supported Morris’ attempts to obtain more pay, and the Morris family remained loyal to Legge during his difficulties with the Council and merchants. Morris did not sign the Council’s petition to the king against Legge.

Morris was appointed a justice of the peace for the town and county of Halifax in December 1750 and a justice of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas for that jurisdiction in March 1752. When a memorial submitted to the Council in January 1753 accused the justices of favouring Massachusetts law and practice over those of England, Morris asserted that his decisions were based upon “the constant Practices in the Court here and in England.” Although the justices were renominated by Hopson, the dissatisfaction influenced the governor’s decision to ask for a chief justice, and in 1754 a person with legal qualifications presided in the courts of Nova Scotia for the first time when Belcher became chief justice.

In 1763 the assembly presented an address to Lieutenant Governor Montagu Wilmot* urging, among other things, the appointment of two assistant judges to the chief justice. John Collier* and Morris were appointed the next year, receiving salaries of £100 a year. Belcher drafted his subordinates’ commissions so narrowly, however, that Collier and Morris could try a case only in conjunction with the chief justice, and they could not even open or adjourn court without his presence and assent. The result was that Belcher could and did ignore them. Richard Gibbons described a case in which Belcher invited his assistants to address the jury. The chief justice then recapitulated the evidence, gave his own altogether different opinion, and instructed the jury to find the verdict as he had advised. Morris was appointed master in the Court of Chancery on 12 May 1764. In that court” Suitors . . . have been so poor, that the Masters have given their Attendance & trouble for nothing.”

After Belcher’s death in March 1776, Legge appointed Morris, as senior assistant judge, to be chief justice until the British government decided upon a permanent appointment. Most of the civil cases tried before Morris were for debt and trespass, and it is evident he had learned considerable law by listening to Belcher. He also presided over criminal cases for larceny, counterfeit, and murder, the trial of Malachy Salter for seditious conversation, and the treason trials of those persons involved in Jonathan Eddy*’s rebellion in Cumberland County. On 15 April 1778 Bryan Finucane took over as chief justice and Morris reverted to the position of first assistant judge of the Supreme Court, a position he held until his death. It was in this role as judge that Morris and his family took the most pride, regarding it as a position of prestige.

The Morris family had the reputation in Nova Scotia of being good administrators and surveyors. Charles Morris was surveyor general of lands for the province for 32 years, a period which saw the founding of Halifax and Lunenburg and the coming of the pre-loyalists, when the colony’s foundations were laid. The Council had every confidence in his decisions and actions, and the chronicler of 18th-century Nova Scotia, John Bartlet Brebner*, praised him for his honest impartiality. Indeed, in spite of the difficulties of these early years of the colony, Charles Morris was “a faithfull Servant of the Crown.”

[The BL and the archives of the Ministry of Defence, Hydrographer of the Navy in Taunton, Eng., hold plans by Morris, but since he did not sign all his work, there are complications in identification. There are numerous map references in G.B., PRO, Maps and plans in the Public Record Office (2v. to date, London, 1967– ), II. PRO, CO 221/38 “is composed of various survey plans, descriptions and notes prepared by Charles Morris” (mfm. at PAC). Some of the PAC holdings are listed in its Report of 1912.

A number of Morris’ works have been published: “Judge Morris’ remarks concerning the removal of the Acadians,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., II (1881), 158–60; “Observations and remarks on the survey made by order of His Excellency according to the instructions of the 26th June last, on the eastern coasts of Nova Scotia and the western parts of the island of Cape Breton,” PANS Report (Halifax), 1964, app.B, 20–28; “The St. John River: description of the harbour and river of St. John’s in Nova Scotia, and of the townships of Sunbury, Burton, Gage, and Conway, lying on said river . . . dated 25th Jan. 1768,” Acadiensis (Saint John, N.B.), III (1903), 120–28. His joint report with Richard Bulkeley, “State and condition of the province of Nova Scotia together with some observations &c, 29th October 1763,” is in PANS Report, 1933, app.B, 21–27. p.r.b.]

Halifax County Court of Probate (Halifax), M154 (will of Charles Morris) (mfm. at PANS). PAC, MG 23, F1, ser.5, 3, ff.421–61 (mfm. at PANS). PANS, RG 1, 29, no.4; 35; 36; 37, nos.18, 20; 39, nos.37–47, 62–63; 163/2, p.54; 164/1, pp.16–18, 33, 48–53, 73–75, 85; 164/2, pp.89–95, 260, 277, 302–4, 315; 165, pp.58–59, 229, 269; 166; 166A; 167; 168, pp.458–60; 169, p.6; 170, p.21; 209, 3 Jan., 29 Dec. 1752, 9 Jan., 5 March 1753; 210; 211, 18 April, 17 May, 17 Aug. 1759, 5 June 1760, 16 Feb., 14 April, 15, 22 May 1761; 212, 22 Oct. 1768, 16 June 1769, 19 Sept. 1770; 359; 361; 363, nos.34, 35, 38; 374; RG 39, J, Books 1, 6; 117. PRO, CO 217/19, ff.290–97; 217/20, ff.43–50; 217/29, f.49; 217/50, ff.85–87, 91–94; 217/51, ff.51–52, 59–61, 70–73, 190–93; 217/52, ff.116–17; 217/55, ff.196–99. Royal Artillery Institution, Old Royal Military Academy (Woolwich, Eng.), “A breif survey of Nova Scotia, with an account of the several attempts of the French this war to recover it out of the hands of the English.” St Paul’s Anglican Church (Halifax), Registers for Windsor – Falmouth – Newport, 1774–95, 4 Nov. 1781 (mfm. at PANS). Boston, Mass., Registry Dept., Records relating to the early history of Boston, ed. W. H. Whitmore et al. (39v., Boston, 1876–1909), [24]: Boston births, 1700–1800, 76. PAC Report, 1904, app.F, 289–300; 1912, app.H. “Trials for treason in 1776–7,” N.S. Hist. Soc., Coll., I (1878), 110–18. PAC, Catalogue of maps, plans and charts in the map room of the Dominion Archives (Ottawa, 1912). Bell, Foreign Protestants, 104n, 237n, 331n, 408, 425–26, 428, 446, 468–74, 569–75. Brebner, Neutral Yankees (1937), 82–84, 90–91, 95–96; New England’s outpost, 131, 234–50, 254. Clark, Acadia, 189n, 344n. Raymond, River St. John (1910), 277–78, 353, 375–76, 473–79. Ethel Crathorne, “The Morris family – surveyors-general,” Nova Scotia Hist. Quarterly (Halifax), 6 (1976), 207–16. A. W. H. Eaton, “Eminent Nova Scotians of New England birth, number one: Capt. the Hon. Charles Morris, M.C.,” New England Hist. and Geneal. Register, LXVII (1913), 287–90. Margaret Ells, “Clearing the decks for the loyalists,” CHA Report, 1933, 43–58. W. F. Ganong, “A monograph of the cartography of the province of New Brunswick,” RSC Trans., 2nd ser., III (1897), sect.ii, 313–425. R. J. Milgate, “Land development in Nova Scotia,” Canadian Surveyor, special edition; proceedings of the thirty-ninth annual meeting of the Canadian Institute of Surveying . . . 1946 ([Ottawa, 1946]), 40–52; “Surveys in Nova Scotia,” Canadian Surveyor (Ottawa), VIII (1943–46), no.10, 11–14.

Cite This Article

Phyllis R. Blakeley, “MORRIS, CHARLES (1711-81),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morris_charles_1711_81_4E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/morris_charles_1711_81_4E.html |

| Author of Article: | Phyllis R. Blakeley |

| Title of Article: | MORRIS, CHARLES (1711-81) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1979 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |