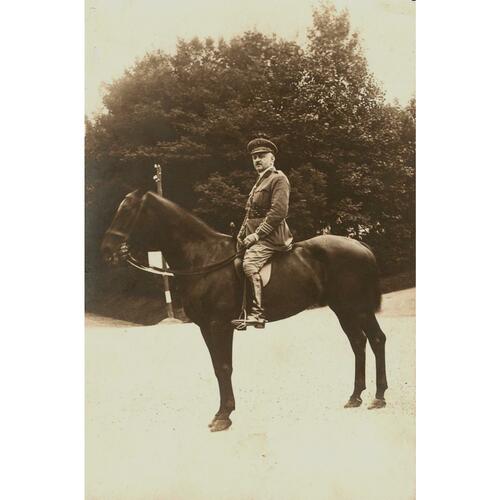

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

MIGNAULT, ARTHUR (baptized Michel-Antoine-Arthur), physician, businessman, philanthropist, and militia and army officer; b. 29 Sept. 1865 in Saint-Denis (Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu), Lower Canada, son of Henri-Adolphe Mignault, a physician, and Marie-Émélie-Valérie Brodeur; m. probably 23 Dec. 1912 Marie-Béatrice Boyer, daughter of Liberal senator Arthur Boyer, in the parish of Saint-Jacques-le-Majeur in Montreal, and they had at least one daughter; d. 26 April 1937 in the same city.

Arthur Mignault did his classical studies at the Séminaire de Saint-Hyacinthe from about 1877 to 1880, and then received his medical training at the Montreal School of Medicine and Surgery (affiliated with Victoria College in Cobourg, Ont.), which at the time was a major rival of the Montreal branch of the Université Laval. After obtaining his degree in 1888, he is thought to have practised medicine in the United States for a few years. Back in Montreal in 1896, he founded the Franco-American Chemical Company Limited towards the end of the century. It was thanks to one of his products in particular, Red Pills for women suffering from anaemia and other illnesses, that he would make his fortune.

A great sportsman, Mignault indulged his passions: polo, hunting with hounds, and horse racing. In 1901 he established the first polo club for French Canadians. He was also one of the few French Canadians to be admitted into private anglophone sports associations such as the Montreal Jockey Club and the Montreal Hunt Club. In addition, he was interested in auto racing, a sport in which he even won a prize in 1904. A philanthropist, in 1913 he donated one of his properties in downtown Montreal for conversion into a playground for disadvantaged children and entrusted its organization and promotion to the daily newspaper La Presse.

Of all his passions, the one Mignault cared most about was probably his military career. He first enlisted in 1892 in the non-permanent active militia as a soldier with the 84th (St Hyacinthe) Battalion of Infantry in which he served until 1899. In 1903 he took up service in the 65th Regiment of Rifles (Mount Royal Rifles) in which, in 1909, he received the title of surgical officer. On the eve of World War I he was captain at Military District No.4 headquarters (Montreal).

Mignault’s renown surged when Canada entered the war. In 1914 he was one of the principal founders of the first French Canadian unit of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the 22nd Infantry Battalion, which would become the Royal 22nd Regiment. Indeed he offered Prime Minister Sir Robert Laird Borden $50,000 to train and equip the battalion, which was composed of French-speaking officers and men. Furthermore, he put automobiles at the disposal of the battalion’s staff officers in Canada and Great Britain. The unit filled its ranks with help from the clergy; the French Canadian media, including La Presse; and eminent political figures such as Sir Wilfrid Laurier*, the leader of the official opposition, Sir Lomer Gouin*, the premier of Quebec, and Raoul Dandurand*, a senator. During the recruitment period, which lasted until May 1915, Mignault offered his services for medical examinations in Saint-Jean (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu).

That year, in March, Mignault’s personal fortune had also been a factor in the creation of a second French-speaking unit, the 41st Infantry Battalion, which was followed by a third, No.4 Canadian Stationary Hospital. Mignault arrived in Britain on 15 May as lieutenant-colonel and commander of the latter. Although it was under Canadian command, this hospital was assigned to France exclusively for the care of French casualties. Throughout the war, it was located at the Saint-Cloud racecourse in the suburbs southwest of Paris. In May 1916, following the appearance of a second French Canadian medical facility in the Paris region, No.6 Canadian General Hospital [see Gustave Archambault], set up by the Montreal branch of the Université Laval, Mignault was promoted colonel and, at his request, became the commanding Canadian medical officer in Paris of both hospitals.

Mignault was not popular with his subordinates, however; at the end of October 1915 his officers had even petitioned for his dismissal. In addition, his management and discipline were investigated by the Canadian military authorities. They criticized him for not paying bills for certain contracts (of which Canadian headquarters in London were unaware) awarded to local businesses. They also blamed him for lax discipline among members of No.4 Canadian Stationary Hospital, which was attributable both to his weak leadership and to the underemployment of the unit by the French military authorities. On a few occasions Mignault put his superiors in an awkward position. One such case concerned expenses submitted for work carried out by French firms, which led to commissions of inquiry and the settling of arrears by the Canadian military authorities.

In November 1916 Mignault received an imperative summons to Canada. The mission to recruit French Canadians, which he had thought temporary, would become permanent. Because of his reputation at home and his organizational talents, he was appointed head of recruiting for the province of Quebec and all of French Canada at a time when the country was having great difficulty in this matter [see Sir Robert Laird Borden]. Prime Minister Borden regarded him as a saviour. Mignault surrounded himself with a team of more officers than he needed, and he spent much of his time in discussions with the authorities. Despite all the effort he expended on this rather thankless task, the situation remained hopeless. Owing to the meagre results he achieved, Mignault was relieved of his post. In April 1917 responsibility for recruiting French Canadians was given to Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre-Édouard Blondin*, postmaster general, and to Major-General François-Louis Lessard*. The latter took Mignault into his service, putting him in charge of recruitment in Military District No.4 (Montreal). In turn Blondin and Lessard failed in their undertaking. In October Mignault was discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force and assigned to the officer reserves. Nevertheless, he kept up his recruiting work, encouraging his compatriots to enlist and calling for the creation of a brigade composed solely of French Canadians.

Mignault’s efforts were first acknowledged by Major-General Sir Eugène Fiset* of Canada’s Department of Militia and Defence in a letter dated 10 Jan. 1917, and then by France, which made him a knight of the Legion of Honour in May. Even after the war Mignault continued to promote military service among young French Canadian physicians.

Once peace returned, Mignault tried his luck at investing his fortune in land and businesses. Unfortunately, the Great Depression of the 1930s completely ruined him and he was deeply distressed. He suffered a stroke that greatly impaired his diction and subsequently lived as a virtual recluse on his wife’s family estate.

Finally, in March 1937, Arthur Mignault received the recognition he had so desired and for which he had waged a long struggle: a military promotion. The new rank of honorary brigadier was the crowning achievement of his military career and, in a way, salved his wounds. Unfortunately, Mignault could not savour his reward for long as he died suddenly the following month.

The author would like to thank Anne and Dominique Perrault for providing details about the life of their grandfather.

BANQ-CAM, CE602-S12, 29 sept. 1865. FD, Saint-Jacques, cathédrale de Montréal [Saint-Jacques-le-Majeur], décembre 1912. LAC, RG 150, Acc. 1992-93/166, box 6160-56; Acc. 1992-93/167, box 7881-100. Le Devoir, 27 avril 1937. La Presse, 1901–37. BCF, 1922. Canadian who’s who, 1936–37. J.‑P. Gagnon, Le 22e bataillon (canadien-français), 1914–1919: étude socio-militaire (Québec et Ottawa, 1986). J. L. Granatstein and J. M. Hitsman, Broken promises: a history of conscription in Canada (Toronto, 1977; repr. 1985). Gilles Janson, “Le Docteur Joseph-Pierre Gadbois, médecin et sportif, 1868–1930” (paper presented at the 51st annual congress of the Institut d’Histoire de l’Amérique Française, Quebec, 1998). Michel Litalien, Dans la tourmente: deux hôpitaux militaires canadiens-français dans la France en guerre (1915–1919) (Outremont [Montréal], 2003). Prominent people of the province of Quebec, 1923–24 (Montreal, n.d.).

Cite This Article

Michel Litalien, “MIGNAULT, ARTHUR (baptized Michel-Antoine-Arthur),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 30, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mignault_arthur_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mignault_arthur_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Michel Litalien |

| Title of Article: | MIGNAULT, ARTHUR (baptized Michel-Antoine-Arthur) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | December 30, 2025 |