McKENNA, JAMES ANDREW JOSEPH, civil servant; b. 1 Jan. 1862 in Charlottetown, son of James McKenna, a merchant, and Rose Ann Duffy; m. 7 Aug. 1888 Mary Joanna Josephine Ryan in Ottawa, and they had five daughters and two sons; d. 30 May 1919 in Victoria.

J. A. J. McKenna attended St Patrick’s School and St Dunstan’s College, educational institutions for Catholics in his home town. He worked briefly for the Prince Edward Island Railway and tried his hand at journalism before moving to Ottawa, where he became a third-class clerk in the Privy Council Office on 11 March 1886. His talent for hard work was noticed; on 23 May 1887 he was assigned to the Department of Indian Affairs, where he became private secretary to the superintendent general, Sir John A. Macdonald*. Throughout the decade that followed, he continued to be employed in the department’s inside service, that is, the headquarters staff. On 1 July 1888 he was promoted to second-class clerk. Meanwhile, he studied law, and his expertise in legal matters was probably decisive in his being chosen for a number of key assignments in the years ahead.

In January 1897 the new superintendent general, Clifford Sifton*, selected McKenna as his private secretary for work connected with the department. Later that year he sent McKenna, along with Thomas Gainsford Rothwell, to work out a settlement with the British Columbia government regarding the administration of the Railway Belt and the Peace River Block, lands that the province had conveyed to Ottawa in order to assist the construction of a transcontinental railway. The second-class clerk was promoted to first-class the following year.

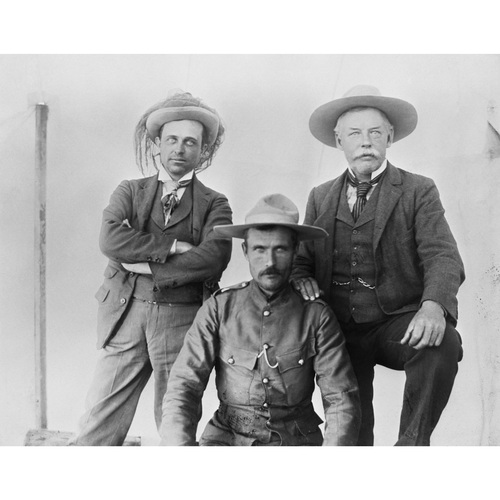

In 1899 McKenna was chosen to join Indian commissioner David Laird and James Hamilton Ross* of the North-West Territorial government in negotiating Treaty No.8 with the Indians in the District of Athabasca and northeastern corner of British Columbia, an area disturbed by gold seekers en route to the Klondike [see Mostos]. The terms offered were similar to those in earlier treaties except that, on McKenna’s initiative, the option of taking land in severalty rather than in reserves was provided. His other proposal, that the Indians be given a lump sum in lieu of annuities, was rejected by Sifton on Laird’s advice. The treaty was successfully negotiated over the summer, with each commissioner following an exhausting itinerary. McKenna visited Fort St John (near Fort St John), B.C., Fort Dunvegan (Dunvegan, Alta), Fort Chipewyan, and Fort McMurray to secure adhesion to the agreement by various bands in meetings that were at times tense.

Land claims from the mixed-blood population of the region were dealt with by separate commissioners who worked in conjunction with the Treaty 8 party. Such claims in the rest of the North-West Territories had not yet been satisfied fully and on 2 March 1900 two new commissions were established to handle them. McKenna and Major James Walker constituted the one for the districts of Assiniboia and Alberta. The large number of claims could not be settled in the allotted time and on 16 March 1901 McKenna was appointed sole commissioner to dispose of those remaining. He continued the work until 1904.

Meanwhile Sifton had decided that McKenna should stay permanently in the west to relieve the ageing Laird of some of his duties and to allow for a more thorough inspection of agencies. On 1 July 1901 McKenna was promoted to assistant Indian commissioner and chief inspector of agencies for Manitoba and the North-West Territories, with headquarters in Winnipeg. In this role he proved to be a staunch champion of his department’s repressive policies, supporting residential schooling and the harsh measures taken against traditional dances and Indian appearances at exhibitions [see Ahchuchwahauhhatohapit; John Chantler Mcdougall].

After Alberta and Saskatchewan achieved provincial status in 1905, Ottawa decided to formalize its relations with any Indians there who were not under treaty. The Cree and Chipewyan in most of northern Saskatchewan and a small portion of eastern Alberta were the intended beneficiaries of Treaty No.10, whose terms were similar to those of Treaty 8. Scrip valued at $240 or 240 acres was designated for the Métis of the region. McKenna was appointed both treaty and scrip commissioner, and he left Winnipeg in August 1906. His late start and anxiety to get home before freeze-up meant that the work was unfinished and had to be continued the following season by the local Indian agent.

McKenna wanted more autonomy for the Indian commissioner’s office and he apparently expected to become commissioner upon Laird’s retirement. But senior officials in the inside service had other plans; they wished to centralize decision-making. In February 1909 it was announced that Laird was moving to Ottawa and that the commissioner’s office would close. McKenna was to stay in Winnipeg as the department’s inspector of Roman Catholic schools for the prairie provinces.

It was a set-back for McKenna but he retained his annual salary of $2,600, which made him the best-paid Indian department officer in the region. His work received recognition in 1911 when the College of Ottawa made him an lld. None the less, he complained of his new duties, which took him on a couple of major inspection tours of Catholic boarding- and industrial schools from Fort Frances, Ont., to St Albert, Alta, and his superiors were not always satisfied with the details of his reports or the pained tone of his correspondence.

Yet he soon received an assignment more to his liking. On 24 May 1912 he became the dominion’s representative in negotiations with British Columbia regarding a number of native grievances. By September he had reached an understanding with Premier Richard McBride that became known as the McKenna–McBride agreement. It allowed for a royal commission with representatives of both governments to examine reserves and adjust their size, with Indian consent. Once this work was done, British Columbia would abandon its troublesome “reversionary interest,” which claimed for the province any land cut off a reserve. McBride refused to put matters such as aboriginal title or native franchise within the scope of the commission and McKenna readily agreed.

The royal commission on Indian affairs for the province of British Columbia was established on 31 March 1913. McKenna was one of the dominion’s representatives and he moved to Victoria with his family. The commissioners travelled throughout the province for three years gathering evidence from natives and non-natives on the adequacy of reserves. McKenna reported regularly to Duncan Campbell Scott*, the deputy superintendent general. He took the occasion to complain of the insufficiency of his $4,000 salary, and his grumbling irritated the penny-pinching Scott, who remained non-committal about McKenna’s request for a permanent position in the Pacific province when the commission concluded.

The commission finished its work on 30 June 1916. Its report recommended certain additions to and cut-offs from reserves. While the acreage to be added exceeded that to be subtracted, the value of the cut-offs was far greater than that of the additions. It seems that the commissioners were more receptive to settler than to native interests.

Scott asked McKenna to stay in Victoria after the commission was disbanded to supervise the printing of the report and to secure British Columbia’s acceptance of it. The documents had not been kept in good order and there were continuous delays in getting everything to the printers. Moreover, the provincial government of William John Bowser* became increasingly preoccupied with the general election it faced in September 1916 and it refused to act on the report. The victory of the Liberals under Harlan Carey Brewster caused further delays, and it was only in 1923, after the clause requiring Indian consent to reserve reductions had been eliminated, that the report was fully accepted.

By the end of 1916, Scott had had enough. In January 1917 McKenna learned that he was to be retired on 1 April. The decision, as Scott explained to the superintendent general, had been postponed out of consideration for McKenna’s large family but had to be taken because of the man’s “unfortunate habits.” These habits were unspecified but they were connected in some way with his failure to conserve the resources his large salary had provided.

McKenna spent his retirement years in Victoria. In February 1918 he published a couple of articles in British Columbia newspapers where he proposed that, in return for control of the Railway Belt and the Peace River Block, the province give up its reversionary interest in reserves and its claim to the cutoffs determined by the royal commission. Scott found the suggestion annoying, especially since he was still engaged in difficult negotiations with the British Columbia government and the Indians on these matters.

On 30 May 1919 McKenna died of heart failure in Victoria. He had been a government official of moderate importance who was associated with a number of significant initiatives in the west during the early decades of the 20th century. His wife and seven children survived him.

James Andrew Joseph McKenna is the author of an article, “Are Canadian Catholics priest-ridden?,” in the January 1891 issue of the Catholic World (New York), 52 (October 1890–March 1891): 541–45, and of The Hudson’s Bay route: a compilation of facts with conclusions (Ottawa, 1908), a propaganda piece written for the government extolling the virtues of a railway to Hudson Bay. His entry in Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912) also credits him with an 1895 pamphlet entitled Sir John Thompson: a study, but no copies of this publication have been located.

NA, MG 26, G: 46012; RG 10, 3822, files 59335-1–3A; 3848, file 75236-1; 3853, file 77144; 3877, file 91839-1; 4044, file 344441. Daily Colonist (Victoria), 19 Feb. 1918. Vancouver Daily Province, 25 Feb. 1918, 31 May 1919. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1900–18, reports of the Dept. of Indian Affairs, 1899–1917; 1902, report of the Dept. of the Interior, 1900/1; Royal commission on Indian affairs for the province of British Columbia, Report (4v., Victoria, 1916). K. [S.] Coates and Fred McGuinness, Manitoba: the province & the people (Edmonton, 1987). K. [S.] Coates and W. R. Morrison, Treaty research report: Treaty 10 (1906) (Ottawa, 1987). René Fumoleau, As long as this land shall last: a history of Treaty 8 and Treaty 11, 1870–1939 (Toronto, [1975?]). D. J. Hall, Clifford Sifton (2v., Vancouver and London, 1981–85), 1; “The half-breed claims commission,” Alberta Hist. (Calgary), 25 (1977), no.2: 1–8. Charles Mair, Through the Mackenzie Basin: a narrative of the Athabasca and Peace River treaty, expedition of 1899 (Toronto, 1908). E. B. Titley, A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, 1986).

Cite This Article

E. Brian Titley, “McKENNA, JAMES ANDREW JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckenna_james_andrew_joseph_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mckenna_james_andrew_joseph_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | E. Brian Titley |

| Title of Article: | McKENNA, JAMES ANDREW JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 14, 2025 |