Source: Link

McCURDY, ARTHUR WILLIAMS, businessman, editor, private secretary, photographer, inventor, and astronomer; b. 13 April 1856 in Truro, N.S., seventh child of David McCurdy and Mary Archibald; m. first 20 Sept. 1881 Lucy O’Brien in Windsor, N.S., and they had three sons and a daughter; m. secondly 2 Oct. 1902 Hattie Maria Mace in Montreal, and they had two daughters and a son; d. 1923 in Washington, D.C.

Arthur McCurdy was born to a prominent Nova Scotian family that traced its lineage back to a son of Daniel McCurdy of Ballykelly (Northern Ireland). This son (Arthur’s great-grandfather), Alexander “the Pioneer,” immigrated to Windsor, N.S., in 1765 after his marriage to Jennet Guthrie; they subsequently lived in Londonderry before acquiring a farm in Onslow. McCurdy’s Presbyterian roots originate with this Alexander, a church elder for 20 years. His paternal grandfather, James, married into the Archibald family of Truro, as did his father.

McCurdy was nine when his father sold the Onslow farm and moved to Baddeck to take over the store established by his son-in-law Angus Tupper, who had died. After finishing public school, Arthur attended the collegiate institute in Whitby, Ont. He was articled as a law clerk for four years in a relative’s firm, W. H. and A. Blanchard in Windsor, but he did not take the bar examinations. Instead, he returned to Baddeck to join the family enterprise, D. McCurdy and Son, from which his father’s attention was diverted in 1873 by his election to the provincial legislature. A year after his marriage in 1881, Arthur acquired his father’s share and, with his brother William Fraser, expanded the business by building a new wharf, opening a meat-curing operation, and starting the Island Reporter, which Arthur edited.

A life-changing event occurred when he met the inventor of the telephone during the visit of Alexander Graham Bell and his wife, Mabel Gardiner Hubbard, to Baddeck in the late summer of 1885. The McCurdys were early users of Bell’s device: William had bought sets to link the store with his home and his father’s. Family lore has it that Arthur was having difficulty with the store phone one day when a stranger walked over and repaired it. “How did you know how to fix that?” asked McCurdy. “My name is Alexander Graham Bell,” replied the visitor. Bell was so taken by Baddeck that, on his return to his home in Washington, he wrote to Mrs Kate M. Dunlop of the Telegraph House hotel, where he had stayed, to say that he and his wife wished to return the next year and acquire a cottage. She recommended Arthur as an agent; the Bells’ first purchase was a farm home on Crescent Grove, next door to his parents. Bell and McCurdy became fast friends – they played chess and each had ceaseless curiosity and a love of invention.

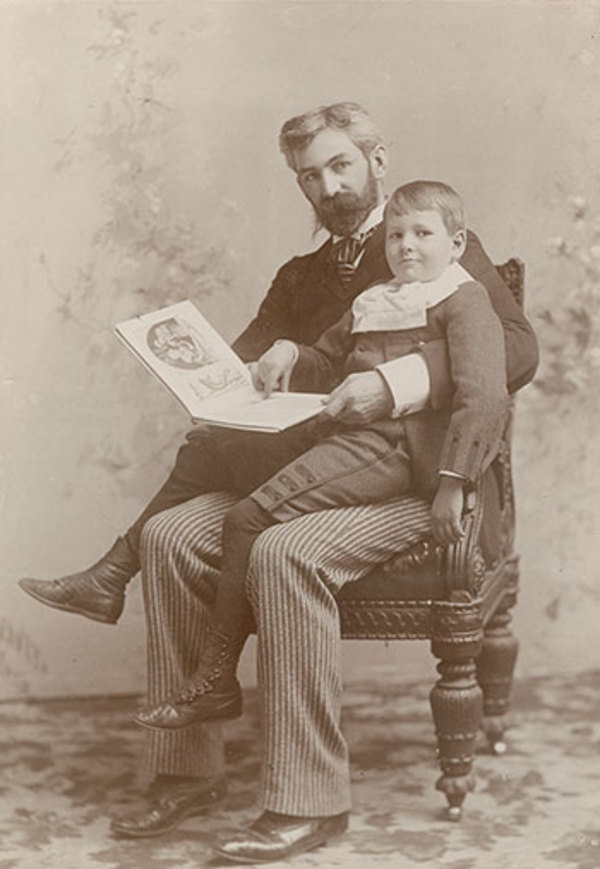

At the same time, McCurdy’s family was growing. His third child, John Alexander Douglas*, was born in 1886. But Cape Breton was entering a period of economic decline, which precipitated the failure of the McCurdy business in 1887. Fortunately, Arthur was offered employment by Bell as his private secretary, and for the next 15 years he would divide his time between Baddeck and Washington. Both Bell and Mabel developed a special bond with the young man. Enthusiastic and driven by a boundless energy, McCurdy cut a striking figure – he was tall and had a prominent moustache and Vandyke beard. An inveterate outdoorsman, he led the Bells on camping trips and taught them how to use snowshoes and shoot. On one visit to a Micmac (Mi’kmaw) village, he photographed them next to two tepees, adjacent to newly constructed telephone poles. Daisy Bell later recalled that he gave her parents “a kind of young friendship that they never had with anyone else. . . . they did things with him that they could never have done without him.”

They soon outgrew their first residence. Bell had fallen in love with Red Head peninsula, on Baddeck Bay, and he tasked McCurdy to acquire the property and 50 adjacent acres. Together they designed The Lodge, the Bells’ rustic home on the point. The association deepened following the death of Lucy McCurdy on 25 March 1888, a week after the birth of another son. Although their children were brought up by Arthur’s sister Georgina, they became part of the Bells’ extended family. The McCurdys could also claim a relationship through Mabel’s mother, Gertrude Mercer McCurdy.

Bell broadened Arthur’s duties in 1889 when he reopened his Washington-based laboratory with McCurdy as one of two assistants. In addition to working on experiments, he took daily dictation of Bell’s thoughts in “Lab Notes” and “Home Notes,” designated by where each book was kept. “You are my private secretary and Alter Ego to the world,” Bell told him in a letter in December 1896. The same exchange revealed that Bell’s office habits could be a source of irritation. “Our work,” he wrote, “is actually in a chaotic condition. . . . This is entirely my own fault, and I sympathize with you in having to work with such an unsystematic man as myself.” McCurdy responded on 28 January with some strong suggestions to Bell to rectify this disarray: “1. You [must] come to the office in some sort of season, and not put off office work until three or four o’clock and in the afternoon. 2. Don’t take letters away from the files of the office and expect me to find them when wanted. 3. Don’t take unanswered letters away, and expect me to answer them.” Along with his administrative duties, McCurdy was the first employee to record visually the inventor’s experiments and activities. Like Bell, he embraced the art and science of photography. He took one of the most famous images of Alexander and Mabel, holding hands during a visit in 1898 to Sable Island, N.S.

In 1899 McCurdy’s love of photography led to the development of one of his own successful inventions. His small portable tank for developing film in daytime, dubbed the Ebedec (the Indian name for Baddeck), has been used by generations of photographers. With financial assistance from Bell, he spent three years commercializing it. After obtaining a United States patent in 1902, he sold the rights to Eastman Kodak. The first model, which he presented to Mabel, is now in the Bell Museum at Baddeck. He left Bell’s employ in 1902 to pursue invention full-time, including a method of printing statistical maps using interchangeable “map type.” Some months later he married Hattie Mace of Sydenham, Ont., a niece of Bell’s stepmother, and they moved to Toronto, where their first child was born in 1903. That same year he was awarded the John Scott premium and medal of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia for his success in invention. A second child was born in 1905 in Baddeck, where, in the summer of 1906, McCurdy’s son Douglas, an engineering student at the University of Toronto, began helping Bell design and fly heavier-than-air craft. The Bells adored Douglas and had tried to adopt him after his mother’s death.

By then, McCurdy had moved his family to British Columbia and set up a laboratory at his country home outside Victoria. He continued to photograph and was active in community affairs; named the first president of the local Canadian Club in 1907, he also pursued his keen interest in nature. For instance, he wrote about Victoria’s climate for the National Geographic Magazine (Washington) in 1907. As president of the Natural History Society of British Columbia, he promoted the establishment of a federal observatory and seismological and meteorological research station, built on Gonzales Hill north of the city in 1913 and headed by Francis Napier Denison*. On 6 March 1914 he chaired a meeting and lecture by federal astronomer John Stanley Plaskett*, at which time the Victoria centre of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada was organized with Denison as president and McCurdy as vice-president. Through his connection to Denison, he lobbied Ottawa to construct a major astronomical facility on Vancouver Island [see William Frederick King*]. Begun on Little Saanich Mountain near Victoria in mid 1915 and opened two years later under Plaskett’s direction, the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory was to house a 72-inch reflecting telescope; installed by May 1918, it was, for a few months, the largest in the world until superseded by the 100-inch instrument at Mount Wilson, Calif.

In 1916 McCurdy had run for a seat in British Columbia’s legislature as the Liberal candidate in the riding of Esquimalt. Although he was declared elected on 21 November by a two-vote margin over Conservative candidate Robert Henry Pooley, he resigned over alleged irregularities in taking the soldiers’ vote. Pooley emerged from a recount with a two-vote victory.

McCurdy died at his Washington home of heart failure in 1923. “He interested himself in the things of life which count,” stated one obituary, and had a “life well spent.”

Correspondence between Arthur Williams McCurdy and Alexander Graham Bell is found in the A. G. Bell family papers (0330M) at the Library of Congress, Manuscript Div., in Washington. The finding aid to this enormous collection, as well as much of Bell’s correspondence, including that with McCurdy between 1889 and 1903, is available on the internet. Many of the photographs taken by McCurdy for Bell are housed in the G. H. Grosvenor coll. in the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Div. The Bell Museum at the Alexander Graham Bell National Hist. Site of Canada in Baddeck, N.S., has the journals known as “Home Notes,” vols.1–135, and “Lab Notes,” vols.1–75. McCurdy is the author of “Factors which modify the climate of Victoria,” National Geographic Magazine (Washington), 18 (1907): 345–48. The year of his death is based on a clipping of an otherwise undated obituary from the Daily Colonist (Victoria), 1923.

BCM-G, RBMB, St George’s Anglican Church (Montreal), 2 Oct. 1902. R. P. Broughton, Looking up: a history of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (Toronto, 1994). R. V. Bruce, Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the conquest of solitude (Boston, 1973). Genealogical record & biographical sketches of the McCurdys of Nova Scotia, comp. H. P. Blanchard (London, 1930). E. S. Grosvenor and Morgan Wesson, Alexander Graham Bell: the life and times of the man who invented the telephone (New York, 1997). Dorothy Harley Eber, Genius at work: images of Alexander Graham Bell (New York, 1982). J. H. Parkin, Bell and Baldwin: their development of aerodromes and hydrodromes at Baddeck, Nova Scotia (Toronto, 1964). A. D. Watson, “Astronomy in Canada,” Royal Astronomical Soc. of Canada, Journal (Toronto), 11 (1917): [47]–78.

Cite This Article

Lawrence Surtees, “McCURDY, ARTHUR WILLIAMS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 28, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccurdy_arthur_williams_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mccurdy_arthur_williams_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lawrence Surtees |

| Title of Article: | McCURDY, ARTHUR WILLIAMS |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 28, 2025 |