Source: Link

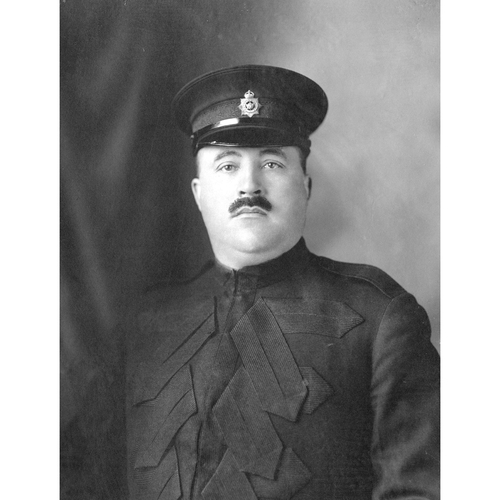

MacLENNAN, MALCOLM BRUCE, tradesman and police chief; b. c. 1873 near Montague Bridge (Montague), P.E.I., son of Duncan McLennan and Margaret Bruce; m. 7 Sept. 1904 Kate Burpee in Vancouver, and they had two sons; d. 20 March 1917 in Vancouver.

Malcolm MacLennan was brought up on Prince Edward Island in a Presbyterian farm family of nine children. Like many Islanders, he left home for Boston and then moved to British Columbia, where he was joined by other family members – three brothers and a sister. Mac, as he was known, worked for several years in construction, lumbering, and carpentry before his appointment as a Vancouver police constable in 1901. During a period of dramatic growth in the city, the burly Maritimer advanced to patrol sergeant in 1907, station sergeant in 1909, and assistant inspector in 1910. His associational links included the masonic order, the Orange lodge, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, and the city’s Prince Edward Island Club. A eulogist would say that he had been “studious to avoid the entanglements of political life.”

Promotion to staff inspector came for him in 1912 under Chief Rufus Gardner Chamberlin. During the disorders brought about by the authorities’ efforts that year to keep the Industrial Workers of the World from holding street meetings, MacLennan’s efforts earned him the respect of moderate elements in organized labour. Upon Chamberlin’s departure in 1913 he was made deputy chief and on 9 Jan. 1914 he became chief. He appointed William McRae, another Islander, his deputy. (At this point Maritimers constituted roughly five per cent of Vancouver’s population.) MacLennan was sympathetic to the rank and file of the force, and his first initiative in the realm of policy was an attempt to secure a weekly day of rest for constables, a suggestion the city council could not support. Indeed, the council was generally reluctant to spend money on the police. Vancouver had the fourth largest municipal force in the dominion, yet departmental headquarters, including lock-ups and the police court, were crammed into a warehouse on Railway Street.

MacLennan’s term as chief coincided with economic recession and middle-class concern about unemployed transients, the Komagata Maru incident [see Mewa Singh], the first years of World War I, the registration of enemy aliens, the drift towards prohibition, and the increasing use of motorized vehicles. Military recruiting and municipal salary cuts contributed to a drop in the size of his department from 286 men in 1914 to under 200 by 1917, but there was a decline in street offences, and the social discipline of the early war years aided the police. Partly because his tenure was brief, MacLennan was untouched by the almost inevitable scandals associated with the enforcement of the morality laws.

During the war the pressure from reformers to deal harshly with violations of those laws did not abate, but some members of the board of police commissioners wanted to segregate a district where vice would be tolerated, and the matter was hotly debated. MacLennan’s major enforcement efforts, judging by press and police commission evidence, were directed against gambling in Chinatown (a target of nativists and moral reformers), prostitution, and illegal drugs. Under political pressure in 1916 the police carried out raids on 26 gambling houses, 173 brothels, and 169 opium dens. They arrested over 1,000 Chinese Vancouverites that year, one quarter of the annual total of arrests.

The Vancouver chief showed his active interest in matters of criminal justice by participating in the Chief Constables’ Association of Canada, founded in 1905. He attended its conventions at Winnipeg in 1914 and Kenora, Ont., in 1916. He envisioned a similar organization for the lower mainland of British Columbia and personally favoured the amalgamation of police forces in that region and the centralization of their administration. In 1917 he urged that a provincial centre be set up for the treatment of drug addicts, who were a cause of periodic moral panics in Vancouver. Incarceration by itself, in his view, was not sufficient to solve the drug problem. He also favoured efforts to divert young people from a way of life that encouraged addiction. He called for the establishment of a reform school for youths too old to be classified as juvenile delinquents, an idea that had been endorsed by the CCAC in 1913. In the meantime the police had to deal with the existing situation. Reporting to the board of police commissioners in January 1917, the chief explained that in order to prevent the maintenance of prisoners in jail from draining the municipal budget the police often gave drug offenders the option of leaving the city.

On 20 March 1917 Robert Tate, a petty criminal originally from Detroit, barricaded himself in a flat on Georgia Street East along with female companion Frankie Russell and a small arsenal. He previously had been arrested for possession of opium, assault, and living off the avails of prostitution. Russell, described by the Vancouver Daily Province as a “depraved woman” and “a white girl of the underworld,” was equally well known to the police. What had originally been a dispute over rent led to the wounding of Tate’s landlord and several policemen and the death of an eight-year-old bystander. Then MacLennan was fatally shot in a police charge into the flat of the “notorious colored desperado.” The press reported the crowd’s sympathy for the idea of lynching the killer. The siege of the house ended when Tate shot himself. A hypodermic needle and traces of morphine were found beside his body.

MacLennan’s death was the fifth police fatality in Canada in five years, and one of the few incidents in which a senior Canadian police official had lost his life on duty. Its sensational aspect underlined for British Vancouverites anxieties about transients, drugs, prostitution, and firearms and about the links between race and deviance. MacLennan’s funeral, held in conjunction with that of Tate’s other victim, was one of the largest in Vancouver to that date.

City of Vancouver Arch., Police commission, minutes, 1912–20; papers, 1914–18. NA, RG 31, C1, 1881, Kings County, P.E.I., Lot 66; 1891, Queens County, P.E.I., Lot 62. PARO, RG 19, ser.3, subser.3, 10 March 1871. Daily World (Vancouver), 21 March 1917. Vancouver Daily Province, 7, 9 Jan., 4, 8 June 1914; 24 Feb., 21, 23, 27 March 1917; 18 June 1918. Vancouver Daily Sun, 21–23 March 1917. Chief Constables’ Assoc. of Canada, Proc. of the annual convention (Toronto), 1914–16. Directory, B.C., 1901. Mark Leier, “Solidarity on occasion: the Vancouver free speech fights of 1909 and 1912,” Labour (St John’s), 23 (1989): 39–66. Norbert MacDonald, “‘C.P.R. town’: the city-building process in Vancouver, 1860–1914,” in Shaping the urban landscape: aspects of the Canadian city-building process, ed. G. A. Stelter and A. F. J. Artibise (Ottawa, 1982), 382–412. Greg Marquis, “Canadian police chiefs and law reform: the historical perspective,” Canadian Journal of Criminology (Ottawa), 33 (1991): 385–406. Joe [G. M.] Swan, A century of service: the Vancouver police, 1886–1986, [ed. L. E. Richardson] ([Vancouver], 1986). Vancouver, Board of police commissioners, City of Vancouver, B.C., Police Department, nineteen hundred and twenty-one, [ed. W. A. Barnes and R. F. Cook] ([Vancouver, 1921?]); Chief constable, Annual report, 1915 (copy in the City of Vancouver Arch.).

Revisions based on:

BCARS, GR-2962, no.04-09-050700.

Cite This Article

Greg Marquis, “MacLENNAN, MALCOLM BRUCE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maclennan_malcolm_bruce_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/maclennan_malcolm_bruce_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Greg Marquis |

| Title of Article: | MacLENNAN, MALCOLM BRUCE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |