Source: Link

MACDONALD, JOHN KAY, office holder, businessman, and philanthropist; b. 12 Oct. 1837 in Edinburgh, youngest son of Donald Macdonald and Elizabeth MacKay; m. 4 Dec. 1867 Charlotte Emily Perley (d. 26 Aug. 1902) in Burford Township, Ont., and they had three sons and one daughter; d. 4 July 1928 in Toronto.

John K. Macdonald’s parents moved from their native Caithness to Edinburgh, where his father was a dairy farmer. The youngest of ten children, John recalled the building of the memorial to Sir Walter Scott but remembered little else of his birthplace before he was sent to join his family in 1845 on a farm in Chinguacousy Township, northwest of Toronto. He attended grammar school in Weston (Toronto), worked on the farm, and then, hoping to become a Presbyterian missioner, entered Knox College in Toronto. In 1863, after one session, he opted for financial administration, as assistant to James Scott Howard*, treasurer of the United Counties of York and Peel. He succeeded Howard in 1866. Following Peel’s separation a year later, he continued as treasurer of York (with offices in Toronto) and was appointed a justice of the peace.

Macdonald was apparently drawn to the study of life insurance in 1869, soon after the federal government had begun regulating the industry. This governance created openings for Canadian companies when a number of American and British firms, faced with maintaining assets in Canada to cover their liabilities, chose to leave instead. As county treasurer, Macdonald understood finance, but he also saw provision for others through insurance as an instrument of social benevolence, a near-religious credence that would never waver. Begun as the Dominion Life Association – its name changed in March 1871 in the process of parliamentary incorporation – the Confederation Life Association was the creation of Macdonald and a group of high-profile business figures. The founding president was finance minister Sir Francis Hincks*, with Lieutenant Governor William Pearce Howland* and Senator William McMaster* as vice-presidents. Named provisional manager in April, Macdonald was pushed to the brink of personal collapse by the organizational burdens: heavy correspondence, chronic eye strain, actuarial preparations, capitalization, travels to Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, and vindictive opposition from John Malcolm Trout, a commercial editor who had been cut out of the controlling clique. In addition, he still held the treasurership of York and troublesome investments he had made in mining operations in Nova Scotia. Although he resigned in July, to be replaced by William McCabe*, Macdonald continued a presence at Confederation Life, which began business in November. He reviewed this business, took out the first policy, was elected a director in December 1872 and a vice-president a year later, and was back with new energy as acting manager in September 1874. Confirmed as manager early the next year, in July he moved the company’s offices from the Masonic Hall on Toronto Street to the nearby Temple Chambers. By this time he had begun his pattern of recuperative trips to the northern bush, “to comfort and rough it” in Muskoka he told his brother Daniel.

For the next two decades, the management of Confederation Life rested heavily on Macdonald’s shoulders as it moved to establish a place among such competitors as Canada Life (established 1847), Sun Life (1865), London Life (1874), and Mutual Life (1874). He made inspection tours of the provinces and territories, built up networks of agents, and spread the gospel of insurance. Some regions required more work than others: “our cause seems virtually dead” in New Brunswick, he lamented in 1877, but adjustments in the Quebec City area had improved business there. The supervision of district agents required much of Macdonald’s time, the firm application of his temperance principles, and a readiness to jettison the errant or the unproductive. After company actuary Professor John Bradford Cherriman* left in 1875 to become federal superintendent of insurance, Macdonald continued their frank exchanges on insurance matters. Ever blunt, he made no secret of his dislike for Cherriman’s early “industrial scheme” for insuring clerks, artisans, and mechanics, favoured reduced rates for clergymen, and in 1880 toyed with the idea of replacing medical examinations with “stiff warranties.” The company’s investments were conservatively sound, mortgages and municipal debentures mostly, and there Macdonald’s knowledge as a county treasurer was beneficial. Though rarely innovative, Confederation Life proved successful: by early 1877, with 5,177 policies and $7,339,167 in insurance in force, it trailed only Sun Life, where Robertson Macaulay* was secretary. Overall, American companies dominated. Macdonald’s own circumstances improved too; in 1881 he was able to withdraw from his ventures in Nova Scotia.

Macdonald’s conduct, professionally and personally, was infused with Christian impulse. His letterbooks reveal a no-nonsense businessman who could easily dismiss gratuitous requests for financial aid, but who could also, fairly and quietly, dispense charity and practical counsel to agents, family, and friends in genuine need. He would later be justly described as “a veteran of Toronto’s business life and in equal degree a veteran of the Cross.” A director from 1866 of the Upper Canada Religious Tract and Book Society, he faithfully looked for opportunities to spread the Word; in 1873 he encouraged the society to consider the lumbermen in the region north of Peterborough. Starting as treasurer of the Young Men’s Christian Association of Toronto in 1866, he also served terms as a vice-president and on its building fund committee. Fully supportive of his ministries, and with him a member of Westminster Presbyterian Church on Bloor Street, his wife was president of the Young Women’s Christian Association. In 1882 he joined the committee of the Presbyterian Aged and Infirm Ministers’ Fund, and five years later he was appointed its convenor. Not surprisingly, he backed broad Protestant causes. He succeeded the Reverend William Caven* in December 1890 as president of the Equal Rights Association, but enjoyed little of Caven’s prestige, and in December 1891 he took the religious high-road as the doxology-singing leader of the Sabbatarian opposition to Sunday streetcars in Toronto. He juggled such causes along with his work and family duties – he and Charlotte suffered the accidental death of a son in 1887 – but for reasons of appearance in business he refrained from going public with his political Conservatism.

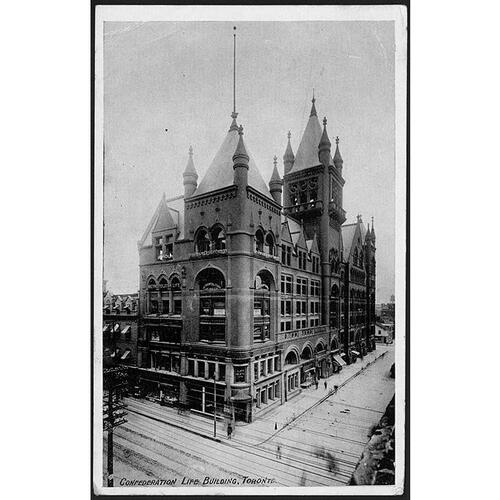

By the early 1890s Toronto teemed with agents for a hundred or so insurance companies, ready to cover a myriad of standard and specialized losses: life, accident, and fire but also cyclones, employer’s liability, livestock, marine, commercial guarantees, and plate glass. J. K. Macdonald’s grand project was the erection in 1889–92 of the red stone and brick Confederation Life Building at Yonge and Richmond streets. This bold, spacious structure gave the company an architectural presence to equal that of Canada Life and Western Assurance, though all would soon be outdone by the Temple Building of the fraternal order of Foresters. Even with a host of other institutional and legal responsibilities, including his executorship of his brother’s estate and the heavily litigated Baldwin estate, Macdonald relished coordinating contractors’ bids, watching the building rise, and fending off criticism of Confederation Life as a commercial landlord. One of the first tenants was the newly founded Toronto Children’s Aid Society; Macdonald replaced John Joseph Kelso* as its president in 1892 and immediately brought his style of officious management to bear on the cause of children’s welfare.

In a letter of 1899 to an ill acquaintance in Hanover, Ont., who Macdonald hoped was ready to meet his Maker, he determined “that a portion of my time shall be reserved for religious and philanthropic work.” This he did, to great public benefit, but the manner of his assistance differed little from his disciplined control of Confederation Life. In 1899 he advised its cashier in Winnipeg to read Isaiah for personal guidance. In 1901–2 he unceremoniously pressured his company’s decrepit president, Sir W. P. Howland, into resignation; within years, he was kindly looking after the property interests of Lady Howland, from whom Sir William had separated. In his various public offices, he took an aggressive interest in finances; he demanded and got accountability. At the Children’s Aid Society, where he encountered untold situations of abject abuse and poverty, he took a direct hand in the care of several wards. After separating a brother and sister from their mother in 1904, he refused to tell her of their whereabouts: “You are utterly unable to look after them.” He dismissed the superintendent of the society’s Shelter in 1902 and the society’s secretary, J. Stuart Coleman, in 1906, and took on the city over its reduced funding of the society. As president of St Andrew’s College in Toronto, he did not hesitate to probe the mental stability of its principal, the Reverend George Bruce, and initiate his dismissal. Macdonald himself resigned in February 1900 when his own son Donald Bruce was appointed to the principalship. He resigned too as president of the Upper Canada Bible Society, in 1901, but his responsibilities remained heavy. In 1896 he had become president of the religious tract and book society, whose sailors’ mission on the Great Lakes was one of his favourite projects. Within the Presbyterian Church, he exceeded his reach when he helped set up an independent mission in India for the Reverend John Wilkie; in 1903–4 he had to stand up for this trouble-making missionary before the Foreign Missions Committee.

One of Macdonald’s few recreational distractions, by about 1897, was Loch Helen, his summer home and farm near Long Bay on Manitoulin Island, where he also fished and hunted. This camp too he managed closely from his desk in the off-season. In August 1902 he was badly shaken by the slow death of his wife from throat cancer at Cona Lodge, their home on Charles Street East. Hours before her passing he was dictating business letters while waiting at her bedside, “expecting that at any moment it may please God to take the spirit from the body.” In September, leaving the “dark shadow that has fallen upon our household,” Macdonald, with one of his sons and his daughter, Charlotte Helen, took a train trip to Halifax. In 1904, at age 66 and again with an attentive Helen, he made his first trip back to the old country. Meanwhile he spent some time and letters musing on his Scottish origins; according to his father, he told Gaelic scholar Alexander MacLean Sinclair, the family had come to Caithness from “the Isles.”

As managing director of Confederation Life, Macdonald continued to oversee its daily operations. He was assisted by his nephew William Campbell Macdonald as actuary and in 1898 his younger son, Charles Strange, joined the company. Routine business included searching out mortgage securities and bidding on municipal debentures (for investment purposes) and supervising and intensifying field operations. By 1896 the opportunity to secure a substantial amount of reinsurance business in the West Indies was attracting the company’s attention, though it would not branch out there and to Mexico until 1901. Macdonald would spend two months in the Caribbean on business in 1906. Extremely aggressive competition blocked its expansion in the United States and Britain until even later. In Canada, Confederation Life trailed Canada Life, Mutual Life, and Sun Life in terms of volume, innovation, and such practices as insuring the young, issuing investment bonds, and eliminating restrictions on residence, travel, and occupation. In 1895, in the midst of an industry-wide slump, Macdonald had dropped his company’s interest rates on policies and reserves, a precedent that earned him the enmity of other managers, despite his role as a founder of the Canadian Life Managers’ Association the year before. Within his company, in 1896 he began “loading” or increasing premiums to meet higher risks but also, he would later admit under examination, to increase profits.

In 1899 a new insurance act widened the range of investment possibilities open to Canadian companies, a regulatory change that would release into Canadian markets a flood of new investment capital. Despite the limitations still in effect under his company’s original charter, and unconscious of any ethical concerns, Macdonald (like other managers) immediately initiated a buying spree, largely in utility and industrial securities and fully supported by his board of directors, which now included such unhesitating capitalists as Wilmot Deloui Matthews*.

New York State’s investigation of the insurance industry in 1905 sent a mild tremor through executives in Canada, but here federal and provincial regulation [see John Howard Hunter*] curbed the wildest excesses and infringements. In the federal royal commission on life insurance of 1906, which exposed Canadian companies to intense scrutiny, full measure was taken of Macdonald’s management and style. Examined on 28 May 1906, he confirmed a complex series of unauthorized and speculative investments between 1900 and 1905, purchases on margin, the elimination of revealing transactions from his company’s statements to the government, concentration of control, and a trail of personal borrowing. The business was legitimate – the brokers used by Macdonald, including Pellatt and Pellatt and Osler and Hammond, were reputable; Edmund Boyd Osler sat on the Confederation Life board. The commissioners, however, held up pure fiduciary principle as a standard, and under examination Macdonald reacted. He displayed memory failure and impatiently sparred with counsel. This was not the sort of conduct he wanted the public to witness, but the Toronto press did not cooperate; the World wondered how such an upstanding citizen could bend the law. In Macdonald’s report on the commission to his company’s agents the following November, he presented a clean finding: there had been no graft and the securities in question were all sound, without “the remotest possibility of loss.” He emerged unblemished, but there would be no more investment bingeing.

Putting the “serious misunderstandings” caused by the commission behind him, Macdonald returned to work and his philanthropic commitments. In the glow of his charitable work, negative impressions of his tight control of Confederation Life faded. He continued as president of the Children’s Aid Society, though his relations with J. J. Kelso, then provincial superintendent of neglected and dependent children, became strained. Kelso thought that the society could do more and that Macdonald resented interference, and in 1916 he would take his concerns before the National Council of Women of Canada and the city’s board of control. Later that year the society allocated funds to improve its children’s shelter. Macdonald remained president until 1921. As well, he served as a vice-president of the Lord’s Day Alliance and on the boards of Knox College, St Margaret’s College, and the Working Boys’ Home. At Confederation Life, he replaced William Henry Beatty* as president in January 1912. Their relations had not always been smooth: in 1901, when Beatty was vice-president, he felt that if agents were expected to collect interest, they should be bonded, and he pressed Macdonald on the matter, only to receive a heated rebuff. After 1912 Macdonald carried on as managing director, a position assumed by his nephew in January 1914. Following W. C. Macdonald’s tragic death at Union Station in January 1917 amid the tumult of wartime troop departures, Macdonald resumed the function, which would be taken over by his son in January 1920, when he also stepped down as county treasurer. The death of his daughter the year before was stoically endured. Through no concerted effort of his own, and possibly as a result of Canadians’ anxieties following the war, Macdonald’s best year in insurance occurred after 1918, when new business shot up from $17,668,072 to $30,652,751.

The acknowledged “dean of life insurance in Canada” continued to maintain an office at Confederation Life, which he visited daily until his death at the age of 90. With his white, centre-parted hair, moustache, and wire glasses, he was a familiar figure walking up and down Yonge Street. His dry humour was rarely witnessed in public. In 1900 he advised an ailing Stuart Coleman that his penchant for writing tediously long letters was what made him sick. When asked once about his stamina, he replied that, as head of the aged and infirm ministers’ fund, he had a lot of old Presbyterian pastors praying for him. Felled by a heart attack on 4 July 1928, he was buried in Mount Pleasant Cemetery; his home was sold to the Children’s Aid Society for use as a shelter. In its editorial eulogy, the Toronto Daily Star lauded John K. Macdonald, the late George Albertus Cox* of Canada Life, and Robertson Macaulay of Sun Life as the three great heads of insurance in Canada.

AO, RG 22-305, no.59917; RG 80-8-0-1086, no.5043; RG 80-27-2, 1: 207. General Register Office for Scotland (Edinburgh), Reg. of births, Edinburgh, 12 Oct. 1837. LAC, MG 28, III 126. Toronto Daily Star, 27 Aug. 1902, 4–5 July 1928. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, reports of the superintendent of insurance, 1875–1921; Royal commission on life insurance, Minutes of evidence (4v., Ottawa, 1907); Report (Ottawa, 1907). Canadian annual rev., 1911, suppl.: 39–48. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898 and 1912). Children’s Aid Soc. of Toronto, Annual report ([Toronto]), 1892–1900. Commemorative biographical record of the county of York . . . (Toronto, 1907). Confederation Life Assoc., 75 years of service, 1871–1946 (Toronto, [1946?]). Morton Keller, The life insurance enterprise, 1885–1910: a study in the limits of corporate power (Cambridge, Mass., 1963). Middleton, Municipality of Toronto, vol.3: 110–11. Toronto Young Men’s Christian Assoc., Annual report (Toronto), 1865–71/72. Who’s who in Canada, 1922.

Cite This Article

David Roberts, “MACDONALD, JOHN KAY,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_john_kay_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_john_kay_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Roberts |

| Title of Article: | MACDONALD, JOHN KAY |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | March 29, 2025 |