Source: Link

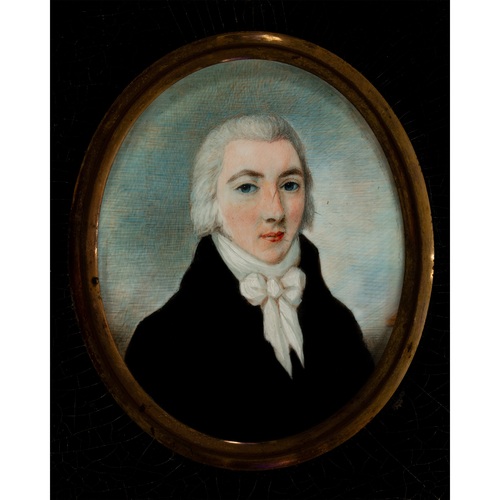

LINDSAY, WILLIAM ROBERT (usually he signed William Lindsay Jr), merchant, militia officer, office holder, and jp; b. 10 May 1761 and baptized two days later in Holborn (London); son of Alexander Lindsay and Susannah Durand; m. 17 June 1790 Marianne Melvin in Quebec City; d. there 11 Jan. 1834, and was buried 14 January in Saint-Charles-Borromée parish at Charlesbourg, Lower Canada.

Born into a Scottish family, William Robert Lindsay was 12 when he joined his uncle William Lindsay in Quebec City. The latter had been sent as a youth to London, where he had become a clerk with merchant Robert Hunter, and then a joint owner in the firm of Lawrie, Lindsay, and Thompson. In Quebec City he went into partnership with a man named Brash. At the time of the American invasion of 1775–76 [see Benedict Arnold*; Richard Montgomery*], he enlisted in the militia, rising to the rank of lieutenant; during the siege of Quebec he kept a journal. Lindsay and Brash took advantage of the war to reorient their commercial activities to meet the new material demands of the colonial authorities. In 1778 he and Adam Lymburner* were the Quebec agents of the London Underwriters, and in 1789 Lindsay was one of the original shareholders in the Dorchester Bridge [see David Lynd*]. In May 1797 he was appointed controller to audit the customs office accounts as well as customs collector at St Johns (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), where he remained until his death in 1822.

In February 1783 William Robert Lindsay went into partnership with merchant William McNider under the name Lindsay and McNider to open a retail store near the harbour, on Rue Saint-Pierre. Their partnership lasted seven years. On 17 June 1790 he married Marianne Melvin; they were to have eight children. (The Melvins had taken in William Burns after the death of his father; now a businessman, he and Lindsay became close friends). That year Lindsay became an ensign in the Quebec Battalion of British Militia and also performed the duties of adjutant with the rank of lieutenant, a rank to which he was in fact promoted around 1795. He was made a captain in the 3rd Battalion of the town’s militia in 1805, and then major in 1812.

While continuing in his dry and wet goods business, Lindsay entered the public service in 1792 as clerk assistant of the Lower Canadian House of Assembly. To these occupations were added those of justice of the peace for the district of Quebec in 1799 and secretary in 1805 of the Union Company of Quebec, a joint stock company founded that year to provide the town with a fine hotel; he also served as the company’s treasurer from 1813. He retained both offices in the enterprise until at least 1823. In a commission dated 6 Dec. 1805 he had been appointed clerk of Trinity House of Quebec [see François Boucher*] and later he also became its treasurer, receiving commissions in 1808 and 1830.

But Lindsay is known above all for his role in the assembly. Having been clerk assistant since 1792, on 7 Aug. 1808, because of “his experience and knowledge,” he was commissioned clerk, replacing Samuel Phillips who was suffering from a “severe indisposition.” He thus was the second person to hold that office in Lower Canada.

When the first session of the fifth parliament opened on 10 April 1809, Lindsay took up his new duties. He received the oaths of allegiance of the members of the Legislative Council and the House of Assembly in the room reserved for the clerk, “commonly called the Ward Robe.” After presiding over the election of Jean-Antoine Panet* as speaker of the house, he was instructed to “revise and print the rules and regulations of the house.” Thus began an arduous, and poorly paid, chapter in Lindsay’s life, under the orders of an assembly insistent on report after report. His tasks multiplied: purchasing items needed in the house, hiring workmen, superintending works, collecting debts, and paying accounts. According to historian Marc-André Bédard, in 1812 the clerk was no longer “a mere secretary to the house but had become in a way its administrator.” That year Lindsay asked for a raise in salary but it was not granted until 1815 and it brought with it the added responsibility of printing bills. Because of his increased workload, he had to hire some “extra writers” or part-time employees. A special committee on the contingent accounts also recommended the appointment of lawyer Robert Christie* as law clerk, and he took up his duties on 26 Jan. 1816.

In 1818, after an inquiry, the special committee pronounced Lindsay’s work satisfactory. The following year, however, there was stricter supervision. The assembly laid down rules for its officials and extra writers. When the house was in session their working hours were to be from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., from 3 p.m. to 8 p.m., and after that until the day’s business was finished. In addition, the assembly insisted that the clerk furnish them with a list of employees and their “respective duties” and salaries. On 26 March 1820 a special committee concluded that all the positions were necessary and gave a vote of confidence to Lindsay, whose role as manager and responsible official was thus confirmed.

But Lindsay’s troubles were not over. In 1824 another special committee, set up to study the assembly’s contingent accounts, recommended an overall reduction of 25 per cent in the salaries of all the “officials and writers,” and also insisted upon the urgent need to enforce work schedules and prevent employees from attending to “any outside matters during their working hours.” Lindsay was at odds with the committee over the translation (especially into French) of the assembly’s official journal and the salaries of those recording the proceedings. In 1828 the assembly passed a motion giving the clerk responsibility for “filling the empty positions in the house” but reserving the right to approve or reject appointments.

These administrative annoyances and the weight of his years severely taxed Lindsay’s health. In November 1828 he had a medical certificate delivered to the speaker attesting that he had been “seriously ill at different times during the summer” and was now “confined to his room.” Dr Joseph Morrin* gave it as his opinion that at his age (67) Lindsay needed “more rest, mentally and physically, than he has had up till now.” Lindsay recommended his son William Burns to the assembly as deputy clerk, a recommendation immediately accepted. On 30 Sept. 1829 young Lindsay officially succeeded his father, who passed away on 11 Jan. 1834.

William Robert Lindsay, who had given unbroken service to the assembly since 1792, founded a veritable dynasty of clerks, for his son was succeeded in that office by his own son, also named William Burns, who held the post until confederation and then became the first clerk of the House of Commons in Ottawa, an office he retained until his death in 1872. Pierre-Georges Roy* praised William Robert Lindsay for having “always given satisfaction to [the] members of the House of Assembly, even though [they were] rather cantankerous and hard to serve.”

[William Robert Lindsay, clerk of the Lower Canadian House of Assembly, is wrongly credited in BRH, 45 (1939): 225–47, with the authorship of “Narrative of the invasion of Canada by the American provincials under Montgomery and Arnold . . . ,” Canadian Rev. and Magazine (Montreal), no.4 (February 1826): 337–52, and no.5 (September 1826): 89–104. The journal, published 50 years after the American invasion, was in fact written by his uncle, William Lindsay, the customs collector at Saint-Jean, who died in 1822. The official documents, such as correspondence, the opinion of General Montgomery, and Governor Guy Carleton*’s replies, are identical, but the original story is sometimes truncated in the BRH version. The biographical note contained in this version confuses the uncle and the nephew, as is revealed in the abundant details on the narrative’s true author found in the article in the February 1826 issue of Canadian Rev. and Magazine.]

ANQ-Q, CE1-7, 14 janv. 1834; CE1-66, 17 juin 1790. PAC, RG 68, General index, 1651–1841: 74, 335, 348, 360, 654, 682. L.C., House of Assembly, Journals, 12 Feb., 25 March 1805; 1808: 23, 45; 1809: 23, 27, 49, 65; 1812; 1815–16; 1818–20; 1823–26; 1828. “Manifestes électoraux de 1792,” BRH, 46 (1940): 99. Recensement de Quebec, 1818 (Provost), 246. Quebec Gazette, index 1778–1823; 9 July 1778; 20 Feb. 1783; 6 May, 17 June 1790; 28 April 1791; 17 May 1792; 8 May 1794; 30 Jan., 10 April 1800; 26 Jan., 23 Aug. 1804; 18 April, 23 May, 12 Dec. 1805; 22 Sept. 1808; 10 Aug., 15 Dec. 1809; 23 April 1812; 28 Jan. 1813; 23 June, 25 Sept. 1823; 13 Jan. 1834. Officers of British forces in Canada (Irving), 145. “Les Presbytériens à Quebec en 1802,” BRH, 42 (1936): 728–29. Quebec almanac, 1791: 43–44; 1794: 88–89; 1796: 82–83; 1801: 102; 1805: 40–41; 1810: 49; 1815: 32; 1820: 82; 1821: 86. P.-G. Roy, Les avocats de la région de Québec, 280. M.-A. Bédard, “Le greffier de l’Assemblée législative du Bas-Canada: origine de la fonction” and “Le Journal et les autres documents publics à l’Assemblée législative du Bas-Canada” in Bibliothèque de l’Assemblée nationale du Québec, Bull. (Québec), 12 (1982), nos.1–2: 35–58, and no.3: 19–57, respectively. P.-G. Roy, “La Trinity-House ou Maison de la Trinité à Québec,” BRH, 24 (1918): 110.

Bibliography for the revised version:

The DBC/DCB would like to thank Ian Lindsay of Aurora, Ont., for providing biographical information taken from two family bibles that belonged to William Robert Lindsay.

Ancestry.com, “London, England, Church of England baptisms, marriages and burials, 1538–1812,” St Andrew, Holborn (London), 12 May 1761: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/1624; “Ontario, Canada, Roman Catholic baptisms, marriages, and burials, 1760–1923,” Ottawa, 4 Sept. 1872: www.ancestry.ca/search/collections/61505 (consulted 28 Sept. 2023). G. R. Swan, “The economy and politics in Quebec 1774–1791” (phd thesis, Univ. of Oxford, 1975).

Cite This Article

Yvon Thériault, “LINDSAY, WILLIAM ROBERT (William Lindsay Jr),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindsay_william_6E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lindsay_william_6E.html |

| Author of Article: | Yvon Thériault |

| Title of Article: | LINDSAY, WILLIAM ROBERT (William Lindsay Jr) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1987 |

| Year of revision: | 2024 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |