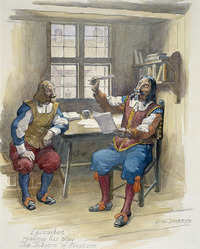

Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

LESCARBOT, MARC, lawyer, traveller, and writer; b. c. 1570 at Vervins in Thiérache, a frontier region between France and the Spanish Netherlands; d. 1642.

His family probably came from Guise, but he himself tells us that his ancestors originated in Saint-Pol-de-Léon, Brittany. He first studied at the Collège in Vervins, then at Laon. Thanks to the protection of Mgr Duglas, the bishop of this latter town, he was able to go and complete his studies in Paris, with a bursary from the Collège of Laon. He received in Paris a very thorough classical education, learned Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and acquired a wide knowledge of ancient and modern literatures. He then studied canonical and civil law.

He graduated as a bachelor of laws in 1598, and took a minor part in the negotiations for the Treaty of Vervins, between Spain and France. At a moment when the discussions seemed doomed to failure, Lescarbot delivered a Latin Discours in defence of peace. After the conclusion of the treaty, he composed a Harangue d’action de grâces, wrote a commemorative inscription, and published Poèmes de la Paix. He was called to the Parlement of Paris as a lawyer in 1599, and translated into French three Latin works: the Discours de l’origine des Russiens and the Discours véritable de la réunion des églises by Cardinal Baronius, and the Guide des curés by St. Charles Borromeo, which he dedicated to the new bishop of Laon, Godefroy de Billy, but published only after that dignitary’s death (1613).

He normally lived in Paris, where he associated with men of letters, such as the scholars Frédéric and Claude Morel, his first printers, and the poet Guillaume Colletet, who wrote a biography of him that has unfortunately been lost. He was likewise interested in medicine, and translated into French a pamphlet by Dr. Citois, Histoire merveilleuse de 1’abstinence triennale d’une fille de Confolens (1602). But he also travelled and maintained contact with his native region, where he had relatives and friends, such as the Laroque brothers, his rivals in poetry, and where he recruited a number of clients. The loss of a case because of the venality of a judge gave him a temporary distaste for the bar. Consequently, when one of his clients, Jean de Biencourt de Poutrincourt, who was associated with the Canadian entreprises of the Sieur Du Gua de Monts, proposed that he accompany them on a voyage to Acadia, Lescarbot lost no time in accepting. He composed an Adieu à la France in verse, and embarked at La Rochelle on 13 May 1606. He reached Port-Royal (Annapolis Royal, N.S.) in July, spent the remainder of the year there, and the following spring made a trip to the Saint John River and the Île Sainte-Croix. But in the summer of 1607 the revocation of de Monts’s licence obliged the whole colony to go back to France.

On his return there, Lescarbot published an epic poem on La défaite des sauvages armouchiquois (1607), then undertook to compose a vast history of the French establishments in America, the Histoire de la Nouvelle-France. The first edition of this work appeared in Paris in 1609, published by the bookseller Jean Millot. The author recounted first the voyages of Laudonnière, Ribaut, and Gourgues to Florida, and those of Durand de Villegaignon and Jean de Léry to Brazil, then those of Verrazzano, Cartier, and Roberval [see Jean-François La Rocque] to Canada. This last part, the least original of his work, is little more than a second-hand compilation.

He next undertook to recount de Monts’s ventures in Acadia, and this part of his book is clearly original. He had spent a year at the Port-Royal habitation and met the survivors of the short-lived settlement at Sainte-Croix; he had talked with the promoters and members of the, earlier voyages, François Gravé Du Pont, de Monts, and Champlain; he had visited old fishing captains, who knew Newfoundland and the Acadian coasts; he therefore reported what he had himself seen or learned from those who had taken part in the events or witnessed them at first hand.

In the successive editions of his Histoire, in 1611–12 and 1617–18, and in his complementary pamphlets, La conversion des sauvages (1610) and the Relation derrière (1612) he reshaped and completed his account. He described the reestablishment of the colony by Poutrincourt, the disputes of the latter and of his son Charles de Biencourt with their competitors and the Jesuits Biard, Massé and Du Thet, and then the ruin of the colony by Argall. He had not seen these incidents, and narrated them only according to Poutrincourt, Biencourt, Imbert, or other witnesses. These testimonies might appear to show some bias, or to be designed for publicity purposes; but Lescarbot, by retaining them, has brought to our knowledge incidents and texts that we would not have known were it not for him.

Lescarbot devoted the whole of the last part of his Histoire to a description of the natives. He was keenly interested in the Indians, and frequently visited the Souriquois (Micmac) chiefs and braves; he observed their customs, made a collection of their remarks, noted down their chants. In many respects he judged them more civilized and virtuous than Europeans, but, like a good Frenchman, he pitied them for their ignorance of the pleasures of wine and love!

Throughout his work, Lescarbot did not confine himself to narration, but expressed many personal ideas. He had very precise opinions about the colonies, which he saw as a field of action for men of courage, an outlet for trade, a social benefit, and a means for the mother country to extend her influence. He favoured a commercial monopoly as a way of meeting the expenses of colonization; for him, freedom of trade led only to anarchy, and produced nothing stable. In Poutrincourt’s dispute with the Jesuits, he obviously sided with his protector; but he could not possibly have composed the Factum of 1614 [see General Bibliography] that some authors attribute to him; he was staying in Switzerland when this lampoon appeared.

All the editions of the Histoire include, as an appendix, a short collection of poems called Les muses de la Nouvelle-France, also published separately. In his dedication to Brulart de Sillery, Lescarbot begs him to forgive those “unkempt and rustically garbed” muses, sprung from the forest. Indeed, if the author did possess real poetic gifts, poetry for him, as for his contemporary Malherbe, was never more than an occasional diversion and a means of pleasing the great. He possessed a feeling for nature and a keen sensibility, and sometimes lighted upon agreeable rhythms and images; but his verse, clumsy and hastily wrought, was dictated by the bad taste of the period and added nothing to his glory.

His Théâtre de Neptune, which is part of the Muses, does however offer some interest. It is a kind of nautical spectacle, organized to celebrate Poutrincourt’s return to Port-Royal. The god Neptune comes in a bark to bid the traveller welcome; lie is surrounded by a court of Tritons and Indians, who recite in turn, in French, Gascon, and Souriquois verse, the praises of the leaders of the colony, and then sing in chorus the, glory of the king, while trumpets sound and cannon are fired. This performance, a mixture of barbarism and mythology, in the impressive setting of the Port-Royal basin, was the first theatrical presentation, and no ordinary one, in North America.

Shortly after the second edition of his Histoire, dedicated to President Jeannin, Lescarbot accompanied Jeannin’s son-in-law, Pierre de Castille, to Switzerland; he went as the secretary of the latter, who had been appointed ambassador to the Thirteen Cantons. Lescarbot must have valued this post, which allowed him to travel, to visit part of Germany, and to frequent the watering-places. He took advantage of the opportunity to compose a Tableau de la Suisse, in poetry and in prose, a half-descriptive half-historical production thanks to which, perhaps, he obtained the, office of naval commissary, and which earned for him when it was published (1618) a gratuity of 300 livres, from the king, This excursion of the poet into diplomacy and administration nevertheless represented only a brief and brilliant episode in his life.

Although he was appreciative of female society, Lescarbot remained for long a bachelor. An idyll with a young lady named de Mouroy, in 1609, had indeed brought him before a notary; they had even drawn up their marriage contract when, for reasons unknown, their splendid plans evaporated and their vows were annulled. Lescarbot was obliged to resort to the law in order to recover an engagement ring that the faithless beauty refused to give back. This misadventure made him cautious. He was nearly 50 when on 3 Sept. 1619, at Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, he married a young widow of noble birth, Françoise de Valpergue, who had been entirely ruined by swindlers; by way of a dowry, she brought him only a fine lawsuit to defend. Her family’s house and estates, burdened with undischarged obligations, had been seized by creditors who had been occupying them for 30 years. Lescarbot, a gallant man and a brilliant lawyer, used all his resources to restore his wife’s heritage. He succeeded in obtaining possession once more of the Valpergues’ house, in the village of Presles, and of an agricultural estate, the farm of Saint-Audebert. But he had to defend these properties tirelessly, in an endless series of court actions, which swallowed up all the slender revenues from these unprofitable lands and embittered the remainder of his life.

In 1629, he endeavoured to attract Richelieu’s attention by two accounts in verse of the siege of La Rochelle: La chasse aux Anglais and La victoire du roy. He kept up his interest in New France and maintained his relations with Charles de Biencourt and Charles de Saint-Étienne de La Tour. The embarkation list of a ship taking supplies to La Tour in 1633 mentions a Marc Lescarbot among the passengers, but it was probably a nephew of the lawyer, with the same first name. We know, however, that he corresponded with Isaac de Razilly. The governor’s reply to one of his letters has been preserved; it is dated 16 Aug. 1634. Razilly gave him interesting details about the founding of La Hève, and invited him to come and settle in Acadia with his wife. But Lescarbot was to spend the last years of his life at Presles. He died childless in 1642, leaving his assets to his brother Claude and to his nephew. His wife survived him.

Lescarbot, a very picturesque figure, has a special place among the annalists of New France. Between Champlain, the somewhat unpolished man of action, and the missionaries concerned with evangelization, this lawyer-poet appears as a scholar and a humanist, a disciple of Ronsard and Montaigne. He possessed the intellectual curiosity, the taste for learning, and the Graeco-Latin culture of the Renaissance. Although a Roman Catholic, he maintained friendships with Protestants, and preserved in religious matters an attitude of independent judgement and of free inquiry that caused him to be considered unorthodox. By all these traits of character, he was a faithful reflection of his period, and showed himself a worthy subject of King Henri IV, whom he venerated.

His abundant and varied literary production is evidence of his intelligence and of the range of his talents. Apart from the works already mentioned, we know that he wrote some manuscript notes and some miscellaneous poems. In addition, he probably composed several pamphlets, published anonymously or left in manuscript, including a Traité de la polygamie, of which he himself spoke. He was also a musician, a calligrapher, and a draughtsman, and Canadian folklorists can claim him as their precursor, since he was the first to record the notation of Indian songs.

But his magnum opus, by its physical size and influence, is surely his Histoire de la Nouvelle-France. This large work went through three editions, adorned with maps. It was written in a pleasant style, was widely disseminated in France and abroad, and received the honour of a German translation and two English ones, by Erondelle and by Purchas. It appears certain, from the numerous quotations from this work, that it exercised a considerable influence, and contributed, among other factors, to the colonial movement that took place in Europe at the beginning of the 17th century. Charlevoix cited him with praise; H. P. Biggar has called him the “French Hakluyt,” and G. Atkinson proclaims him “the best of the historians of New France.” Despite the reservations which judgements so favourable might call for, it remains evident that Lescarbot is the author of one of the first great books in the history of Canada.

The second edition of the Histoire de la Nouvelle-France (Paris, 1611 et 1612) was reproduced by Edwin Tross (3v., Paris, 1866). The third edition (Paris, 1617 et 1618) has been reprinted, with an English translation which in part follows that of Erondelle, by W. L. Grant with Introduction by H. P. Biggar (3v., Champlain Soc., I (1907), VII (1911), XI (1914)). Le Théâtre de Neptune en la Nouvelle-France has been re-published separately and translated as The Theatre of Neptune in New France, by H. T. Richardson (Boston, 1927). ... ACM, B.5654, no.33. AN, H, 28037; T, 201143; X1b, 1135; Y, 160, f.323; Minutier central des notaires, une quinzaine d’actes. Bibliothèque de Laon, MS 166bis, tome 1, p. 123. BN, Imprimés, Rés. Thoisy 414, f.336; Rés. Z. Payen 1064, p. 69; MS, Fr. 4519, f.153v; 13423, f.349; MS, Lat. 9956, f.3; MS, NAF 9281 (Margry), f.9. ... G. Atkinson, Les nouveaux horizons de la Renaissance française (Paris, 1935), passim; Les relations de voyages français du XVIIe, siècle et l’évolution des idées (Paris, 1927). V. Beuzart, “La religion de Marc Lescarbot,” Société de l’histoire du protestantisme français Bulletin, LXXXVII (1938), 237–60. H. P. Biggar, “The French Hakluyt: Marc Lescarbot of Vervins,” AHR, VI (1901), 671–92. G. Chinard, L’Amérique et le rêve exotique dans la littérature française au XVIIe siècle et au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1913), 100–15. A. Demarsy, Note sur Marc Lescarbot, avocat vervinois (Vervins, 1868). A. Jal, Dictionnaire critique de biographie et d’histoire (2e éd., Paris, 1872). La Thiérache: Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Vervins (Aisne, 1873–1949) contains several articles on Lescarbot by M. Noël, M. G. Lecoeq, E. Dedrus, E. Creveaux, and others..

© 1966–2024 University of Toronto/Université Laval

Image Gallery

Cite This Article

René Baudry, “LESCARBOT, MARC,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 19, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lescarbot_marc_1E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lescarbot_marc_1E.html |

| Author of Article: | René Baudry |

| Title of Article: | LESCARBOT, MARC |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 1 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1966 |

| Year of revision: | 1979 |

| Access Date: | April 19, 2024 |