Source: Link

KLENMAN, ABRAHAM, pioneer Jewish farmer and communal leader; b. c. 1830 in Bessarabia; m. Fayga (Faye) —, and they had four daughters; m. secondly Pearl Oodel, and they had two sons and one daughter; d. 1910 near Wapella, Sask.

In the wake of pogroms and of discriminatory legislation in 1882, thousands of Russian Jews emigrated to North America. Among them, arriving in Montreal in 1888, were Abraham Klenman and his extended family from Soroca (Soroki), in a region of Bessarabia then held by Russia but now part of Moldova. The party included his second wife and their children, two of Klenman’s daughters by his first marriage, his son-in-law Solomon Barish, and the Barishes’ three children. Klenman had substantial experience in agriculture, having farmed rented land as a young man and overseen an estate for an absentee Russian landlord; Barish had farmed in the Jewish agrarian colony of Dombroveni, also in Bessarabia. Barred from owning land in Russia because he was a Jew, and believing that a return to the land was necessary for the Jews to become regenerated as a people, Klenman aspired to move to western Canada and settle on one of the quarter-section homesteads being offered by the Canadian government for a registration fee of ten dollars.

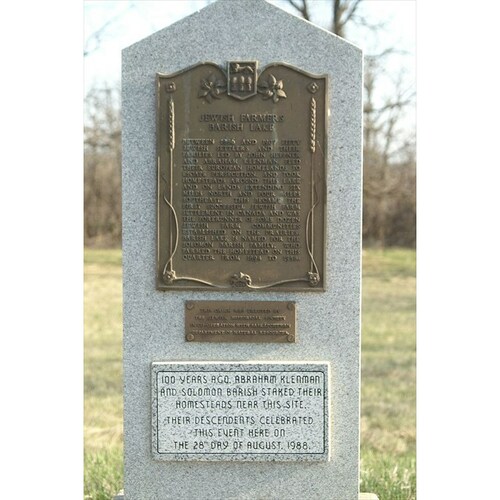

In Montreal, Klenman investigated and promoted the idea of an agricultural colony in western Canada to consist of a number of immigrant Jewish families, and he selected some of the settlers. Barish meanwhile supported the extended Klenman family by working in a cigar factory. In the fall of 1888 Klenman and another Jewish immigrant, Jacob Silver, were chosen to seek suitable land. Assisted by Lauchlan Alexander Hamilton, land commissioner of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company in Winnipeg, Klenman and Silver travelled to various localities. Eventually they decided to settle in the aspen parkland belt, in order to utilize the trees for buildings and fuel, and to take advantage of a water-table that was near the surface, not at considerable depth as on the plains. They learned that the John and Rachel Heppner family and same other Russian Jews, supported by Anglo-Jewish philanthropist Hermann Landau, in 1886 had located in the fast-growing area a few miles northeast of Wapella, a village on the CPR main line. The first Jewish farming colony in western Canada, New Jerusalem, which had been founded in 1884, was some 30 miles southeast. Klenman decided to take up land adjoining the Heppners’ farm, while Silver returned to Montreal to encourage other Jews to come out.

Klenman had only dug a cellar when winter set in, and thus was forced to pass his first prairie winter below ground; he finished his log house with a straw roof in the spring of 1889, when all his extended family except for Barish, along with several other Jewish immigrants, came to the Wapella colony. As they had done for the Heppner settlers, the Department of the Interior and the CPR agreed to interchange land, so that Klenman was able to obtain adjacent homesteads for the would-be farmers. A compact tract of land was essential for them, not only to make possible mutual aid and comfort in a strange country but also to meet the requirement of Orthodox Judaism that to conduct a religious service at least ten men must be present. For the immigrants, practising Judaism was a daily way of life, and transportation based on slow oxen and prairie trails meant that a distance of even a few miles apart was impractical. On their sabbath they had to walk to services because their religion forbade making animals work on that day.

Between the spring of 1889 and the fall of 1892, 28 Jewish families followed Klenman to the Wapella district, one being that of Ekiel Bronfman. By 1907 about 50 families had come. Most of the Wapella settlers were from southern Russia and Bessarabia, with some from Romania, Galicia, and Lithuania. A few had been farmers in North Dakota, others had worked on the construction of the CPR, but the majority had been tailors, shoemakers, labourers, and pedlars. Klenman paid the homestead registration fee for many of them. In Montreal Barish’s doctor had prescribed fresh air to treat consumption. This advice hastened his plan to become a farmer. On request from Klenman, who underwrote his expenses, and other Wapella colonists, he trained for a year in Chicago to become a ritual slaughterer and a ritual circumciser. He arrived in Winnipeg in 1892 on his way to Wapella.

As the patriach in the colony, Klenman provided for the religious requirements of the people. The Wapella Hebrew Congregation, which met in the colonists’ homes, was formed, and a cemetery established on land donated by Klenman. In 1889 Edel Brotman, a rabbi in his native Galicia, took up a homestead, and for the next 16 years acted as a farmer-rabbi. After his departure, Barish or itinerant religious men looked after the spiritual needs of the colony. The Jews of Wapella, being few in number, shared with their non-Jewish neighbours school facilities, various social and business organizations, and other aspects of rural life.

Led by Klenman, the settlers engaged in private-enterprise mixed farming. Some supplemented their incomes by cutting firewood and hauling it for sale in the villages of Wapella, Rocanville, and Moosomin. With the exception of the Heppners, they began their rural existence without financial and organizational assistance from government and philanthropic associations, and in comparison with some other Jewish farming colonies, such as New Jerusalem, they exhibited a strong will to succeed. Only in 1901, after their crops had been destroyed by frost, were Wapella farmers forced to obtain loans, which they repaid completely within 17 years. The funds were advanced through the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society of New York from the Jewish Colonization Association, a philanthropic organization which assists Jews to emigrate from countries where they are persecuted or economically depressed and helps them to settle elsewhere in productive employment. Wapella became the first successful and the longest-surviving Jewish farm colony in Canada and it served as the mother settlement and training ground for several other Jewish agricultural communities.

Klenman spent the rest of his life on his farm. In the 1890s, he kept in touch with world and Jewish events by subscribing to the Jewish Gazette, published in Yiddish in New York. When he could no longer perform daily farm work, he served the colony as a Hebrew teacher. His son Alexander had gone to live in Brandon, Man., and when Abraham Klenman died in 1910, he was interred in the Brandon Jewish cemetery. After her husband’s death, Pearl Klenman moved to Brandon, where she died in 1928. Klenman descendants farmed at Wapella until the early 1960s.

[Additional information was obtained by the author in his 1992 telephone interviews with historian Cyril Edel Leonoff of Vancouver and with Allan Klenman of Victoria, a grandson of the subject. h.t.]

Jewish Hist. Soc. of Western Canada Arch. (Winnipeg), Newspaper database; Vertical files. PAM, MG 10, F3, Abraham Klenman family tree. Maurice Lucow, “Cemetery last trace of Jewish farm colony,” Canadian Jewish News (Toronto), 5 Sept. 1991, Rosh Hashanah supp.: 30–31. Louis Rosenberg, “Wapella: the oldest existing Jewish farm colony in Canada,” Israelite Press (Winnipeg), 25 Dec. 1929: 4. A. J. Arnold, “The Jewish farm settlements of Saskatchewan: from ‘New Jerusalem’ to Edenbridge,” Canadian Jewish Hist. Soc., Journal (Windsor, Ont.), 4 (1980): 253; “Jewish immigration to western Canada in the 1880’s,” Jewish Canadian Hist. Soc., Journal (Windsor), 1 (1977): 82–96; “Jewish pioneer settlements,” Beaver, outfit 306 (1975–76), no.2: 20–26; “New Jerusalem on the prairies: welcoming the Jews,” Visions of the New Jerusalem: religious settlement on the prairies, ed. B. G. Smillie (Edmonton, 1983), 91–107. C. E. Leonoff, The architecture of Jewish settlements in the prairies: a pictorial history ([Winnipeg, 1975]); “Early Jewish agricultural colonization in Saskatchewan,” Sask. Hist., 36 (1983): 58–69; Pioneers, ploughs and prayers: the Jewish farmers of western Canada (Vancouver, 1982); Wapella farm settlement (the first successful Jewish farm settlement in Canada): a pictorial history (Winnipeg, 1972).

Cite This Article

Henry Trachtenberg, “KLENMAN, ABRAHAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/klenman_abraham_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/klenman_abraham_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Henry Trachtenberg |

| Title of Article: | KLENMAN, ABRAHAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 29, 2025 |