Source: Link

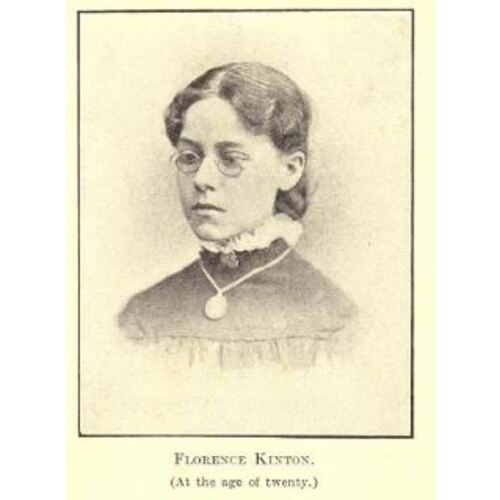

KINTON, ADA FLORENCE, artist, teacher, Salvation Army officer, and newspaper editor; b. 1 April 1859 in Battersea (London), England, daughter of John Louis Kinton and Sarah Curtis Mackie; d. unmarried 27 May 1905 in Huntsville, Ont.

Florence Kinton’s family were middle-class Methodists; her father taught literature at a Wesleyan training college. At the age of 23 Florence obtained an art-master’s certificate. Immediately after her father’s death in December 1882 she paid a prolonged visit to her brothers, Edward and Mackie, who had emigrated to the Muskoka region of Ontario. In 1883 she returned to England and began teaching art at a ladies’ boarding-school. It was during the Christmas holidays of 1883 that she was introduced to Salvation Army founder General William Booth and his family by her sister, Sara Amelia, who was temporary governess of the Booth children. Over the next few years she attended some Army meetings. Her growing evangelical feelings prompted her to resign her position at the boarding-school, she explained in a letter of September 1885, but perhaps as important was her desire to further her art career. She took postgraduate courses at the South Kensington school of art, which advised her to attempt to establish an art-school in Canada.

In June 1886 Kinton emigrated to Canada, where she taught art first in Kingston, Ont., and then in Toronto. She must not have been completely satisfied, for in the spring of 1889 she experienced a deep conversion and decided to join the Toronto Salvation Army as an officer. In an account published in January 1892, she described her sudden renunciation of the worldly pleasures of middle-class femininity: “I took my scissors and with ruthless fingers ripped off the superfluity of ornaments – bright bows, and lace and trimming. Thenceforth I must dress in all simplicity. I went to my wardrobe and lifted from the hooks things of which I had an unnecessary supply. I strapped them in a bundle, ready for the [Army’s] Rescue Home.” She also cut her hair quite short.

The Salvation Army was the only religious organization of the time in which women were allowed to become the equivalent of clergy. This acceptance undoubtedly helps to explain the predominance of female officers. Even more striking is the fact that most of these women were working-class, many of them former domestic servants. Kinton’s atypical education and class background fitted her for positions such as the associate editorship of the Army’s paper, the Canadian War Cry, which she held in the early 1890s. Though she had become a captain by 1891, she never rose higher in the ranks, unlike other early, middle-class female recruits, the most notable example, perhaps, being Blanche I. Read Johnston, who led the women’s social work department and attained the rank of brigadier.

From 1889 to 1891 Kinton served in many of the new social-work institutions run by the Army in downtown Toronto: the Drunkard’s Home, the Children’s Shelter, and the Rescue Home for women. Taken ill with typhoid and malaria late in 1891, she went to convalesce with her sister, who had settled in Huntsville. It was upon her return in 1892 that she was appointed associate editor of the War Cry, a task which also involved writing brief pieces and doing some of the melodramatic drawings found in the paper at this time.

More comfortable with writing, and certainly with illustrating, than the average Canadian salvationist, Kinton might have attained the relatively powerful position of controlling the Army’s paper. In 1893, however, she was asked by the new commandant for Canada, Herbert Henry Booth (one of the general’s sons), to become “private secretary” to his wife, Cornelie, a post which evidently included responsibility for the Booths’ three children. Kinton accepted and thereafter submerged any personal ambition she might have had, virtually ceasing to write or produce artwork. The unpopularity of Booth as Canadian commander probably also helped to marginalize Kinton.

In the spirit of self-denial that had come over her in her conversion, she was apparently content to look after the Booth children and perform any other task Mrs Booth asked of her. That she enjoyed children is clear from her earlier, highly sentimental accounts in the War Cry of neglected and abused Toronto children “rescued” by the Army. In these accounts drunken mothers were providentially replaced by kindly salvationists (no doubt modelled on Kinton) who taught small children that they must love Jesus best of all. While other officers married and had children, in addition to working with society’s outcasts, Kinton remained a glorified servant. She went so far as to accompany the Booths to Australia after Herbert was replaced by his sister Eva in 1896.

In Australia Kinton contracted tuberculosis, but she did not leave the Booth family until a sister of Mrs Booth came from England in 1902 to help. That same year Herbert broke with his father and resigned from the Army. Kinton’s commitment to the family, however, appeared unshaken. She returned to Huntsville, but, ignoring her sister’s advice to enter the Army’s New York headquarters, she soon rejoined the Booths, first in Evanston, Ill., and then in New York. In 1903 her health took a turn for the worse and she again retired to Huntsville, where Sara nursed her through her final illness.

Not a renowned success as an artist or as a salvationist, Kinton, one could still argue, had lived a worthwhile life. The writings that can be clearly identified as hers are evidence of how the “blood and fire” of the early Salvation Army led one woman to leave the conventions of middle-class femininity, including an interest in marriage, far behind in her quest for a life of self-denial and social service.

The vast majority of illustrations and many of the short articles in the Canadian War Cry (Toronto) are unsigned, so it is difficult to establish their authorship precisely. Some of Ada Florence Kinton’s contributions, as well as some of the pamphlets she prepared, are excerpted or reproduced in Just one blue bonnet: the life story of Ada Florence Kinton, artist and salvationist; told mostly by herself with pen and pencil, edited by her sister, Sara Amelia [Kinton] Randleson (Toronto, 1907). Florence’s description of her conversion appeared under the title “Every chain” in the Salvation Army magazine Deliverer (London), 3 (July 1891–June 1892): 121, available in the Salvation Army Heritage Centre, Toronto.

NA, RG 31, C1, 1891, Huntsville: 40, 44 (mfm. at AO). Lynne Marks, “The ‘hallelujah lasses’: working-class women in the Salvation Army in English Canada, 1882–92,” Gender conflicts: new essays in women’s history, ed. Franca Iacovetta and Mariana Valverde (Toronto, 1992), 67–117. R. G. Moyles, The blood and fire in Canada: a history of the Salvation Army in the dominion, 1882–1976 (Toronto, 1977). Mariana Valverde, The age of light, soap, and water: moral reform in English Canada, 1885–1925 (Toronto, 1991). War Cry, 1892–93 (available on mfm. at the Salvation Army Heritage Centre).

Cite This Article

Mariana Valverde, “KINTON, ADA FLORENCE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kinton_ada_florence_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kinton_ada_florence_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mariana Valverde |

| Title of Article: | KINTON, ADA FLORENCE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |