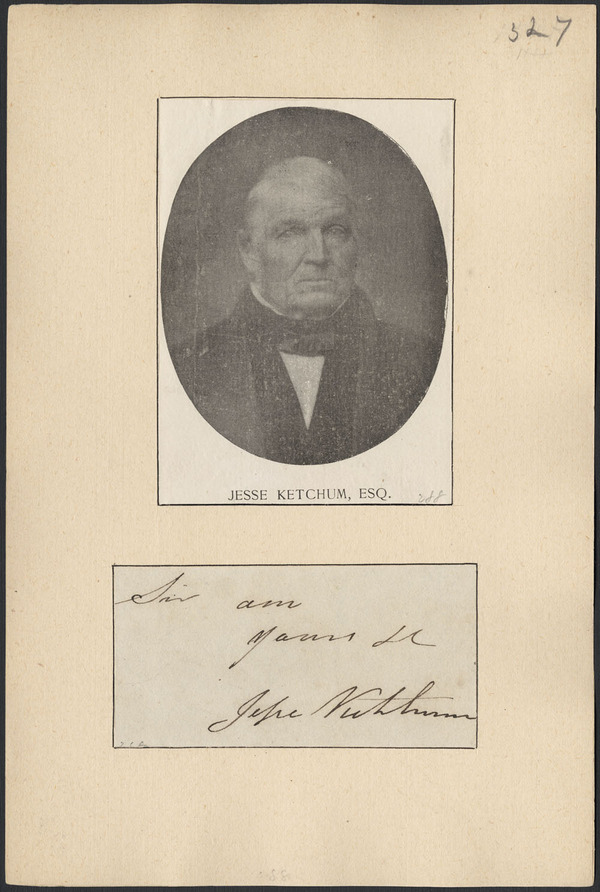

KETCHUM, JESSE, tanner, politician, and philanthropist; b. 31 March 1782 at Spencertown, Columbia County, N.Y., fifth son of Jesse Ketchum and Mollie Robbins; m. first Ann Love (d. 1829), by whom he had three sons and three daughters, and secondly Mary Ann Rubergall, by whom he had three children; d. 7 Sept. 1867 at Buffalo, N.Y.

Following the death of his mother when he was six years old, Jesse Ketchum was taken into the home of a tanner in Spencertown where he probably learned the tanning trade. Unhappy in his foster home because his efforts to attend school were frustrated, Ketchum ran away at the age of 17 to join his brother, Seneca*, who had come to Upper Canada in 1796 and was farming on Yonge St north of York (Toronto).

On the outbreak of the War of 1812 some recent arrivals from the United States left Upper Canada rather than serve in the militia or swear allegiance to the crown. One such individual, John Van Zandt, an American tanner at York, was obliged to dispose of his property at once, and no doubt at a sacrifice. Ketchum was the purchaser. Like other merchants, he profited greatly from the wartime demand for supplies for the troops. A shrewd businessman, Ketchum invested his profits in town property in York, and also bought and sold farms in the county of York.

At the beginning of the war Ketchum joined the 3rd Regiment of York militia, and was among those paroled after the capitulation of York to the Americans in 1813. Nevertheless, his loyalty came under suspicion during the brief American occupation, and he was one of those whom Attorney General John Beverley Robinson was subsequently directed to have arrested and tried if, upon inquiry, that action seemed justified. No arrest occurred, but the episode no doubt had a lasting effect upon Ketchum.

Ketchum was a public spirited and generous man. He subscribed to the rebuilding of the Don bridges after the war; he became a member of the Society for the Relief of Strangers in Distress (renamed the Society for the Relief of the Sick and Destitute in 1828); and he was on the board of health. After the passage in 1816 of the Common Schools Act, which provided legislative support for administrative costs but not for the erection of school buildings, Ketchum subscribed to the building fund of the first common school in York. It was completed in 1818, and he was elected by the townspeople to its board of trustees. In 1832 he provided at his own expense for an infant school for children under seven.

Ketchum first became opposed to the Family Compact and sympathetic to the radical party in 1820 as a result of John Strachan’s involvement with the common school of York; Strachan persuaded Lieutenant Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland* to withhold funds for the school, and, when the elected trustees resigned, was successful in replacing their choice of teacher, Thomas Appleton, with his own Anglican nominee, Joseph Spragg*. A second factor was the clergy reserves question. Although a Methodist himself, Ketchum was no narrow sectarian. He attended St James’ Anglican Church when it was the only church in York, and, with gifts of land and money, he helped to establish a Methodist chapel in 1818, as well as a secessionist Presbyterian church (later Knox Presbyterian Church) in 1820. He taught Sunday school in the Methodist church and took a keen interest in Sunday schools of all denominations. In 1823 he founded the York Sunday School Union to establish libraries for children attending these institutions. This broad-minded man was chosen chairman of a public meeting called in December 1827 to protest against Strachan’s famous “Ecclesiastical Chart” and his efforts to secure the clergy reserves wholly for the Church of England. Ketchum’s name headed the list of those from the Home District who, in 1828, petitioned for a liberalization of the charter of King’s College. In 1831 another petition was drawn up by Ketchum and Egerton Ryerson* and signed by “Friends of Religious Liberty,” asking the imperial parliament to place all denominations in the province on a footing of equality and to appropriate the clergy reserves to general education and public works.

By 1828 Ketchum had become well known as an opponent of the Family Compact. In that year the county of York elected him and William Lyon Mackenzie to the assembly. Ketchum held his seat until 1834, when he declined to run again, disliking the hurly-burly of politics. During these years he had so much influence with Reformers, supported them so fully, and worked so closely with Mackenzie for constitutional and other reforms that his opponents called him “King Jesse” and Mackenzie “King Jesse’s jackal.” Ketchum opposed the expulsions of Mackenzie from the assembly, did his best to have him reinstated, and in the process suffered in the York riots of 1832.

Ketchum’s withdrawal from political life in 1834 did not mean withdrawal from public affairs. He helped to organize the Canadian Alliance Society, founded in December 1834 to further the demand for reform, and he was an active member of the society’s vigilance committee which collected much of the material Mackenzie included in The seventh report . . . on grievances (1835). When in 1836 Sir Francis Bond Head* dismissed the Executive Council and replied rudely to delegates presenting a petition of public protest, Ketchum helped to draw up the indignant and sarcastic response of the Reformers, and he and James Lesslie* were delegated to deliver it to the lieutenant governor. Ketchum continued to hope to secure reforms by peaceful means, though talk of rebellion began in 1837. He did not attend the meeting of Reformers at John Doel*’s brewery on 31 July 1837, because he knew that Mackenzie would propose a coup d’état. He refused to sign the resulting declaration of Toronto Reformers, broke with his former political associates, and took no part in the rebellion.

Soon after the rebellion Ketchum, though he remained in Toronto, moved his tannery to the outskirts of Buffalo, a location which gave his business wider prospects and which provided security for his son, William, who had fled Upper Canada in the aftermath of the rebellion. Moreover, the Toronto site had now grown too valuable for use as a tannery. Ketchum invested his profits from the Buffalo tannery in nearby farm lands which, as the city expanded, became very valuable. He had many interests to keep him in Toronto, including large real estate activities. In 1845, however, he decided to turn over his property in Toronto to the children of his first marriage and, with his second family, move to Buffalo where his extensive real estate developments now required his presence.

In Ketchum Toronto lost a generous citizen who had given building lots to his employees and who, before leaving for Buffalo, secured employment for them. He was vice-president of the York Temperance Society, founded in 1830, and built two halls for the society’s meetings. He was a founder of the Upper Canada Bible Society in 1828, and of the Upper Canada Tract Society established in 1832. He also endowed these societies with funds to enable them to present prize books annually to school children and to the Sunday schools. He was a founder, in 1830, of the Home District Savings Bank which served the town’s working class, and two years later helped to organize the York Mechanics’ Institute. In Buffalo Ketchum continued his benevolences to churches, schools, and temperance societies and he made annual gifts of books to the school children. He died in 1867. On the day of his funeral the schools of the city were closed in his honour.

Scadding, Toronto of old (1873). Town of York, 1793–1815 (Firth). Town of York, 1815–34 (Firth). E. J. Hathaway, Jesse Ketchum and his times: being a chronicle of the social life and public affairs of the capital of the province of Upper Canada during its first half century (Toronto, 1929). Lindsey, Life and times of Mackenzie. Municipality of Buffalo, New York; a history, 1720–1923, ed. H. W. Hill (4v., New York and Chicago, 1923). Sissons, Ryerson.

Cite This Article

Lillian F. Gates, “KETCHUM, JESSE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 18, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ketchum_jesse_9E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ketchum_jesse_9E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lillian F. Gates |

| Title of Article: | KETCHUM, JESSE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1976 |

| Year of revision: | 1976 |

| Access Date: | December 18, 2025 |