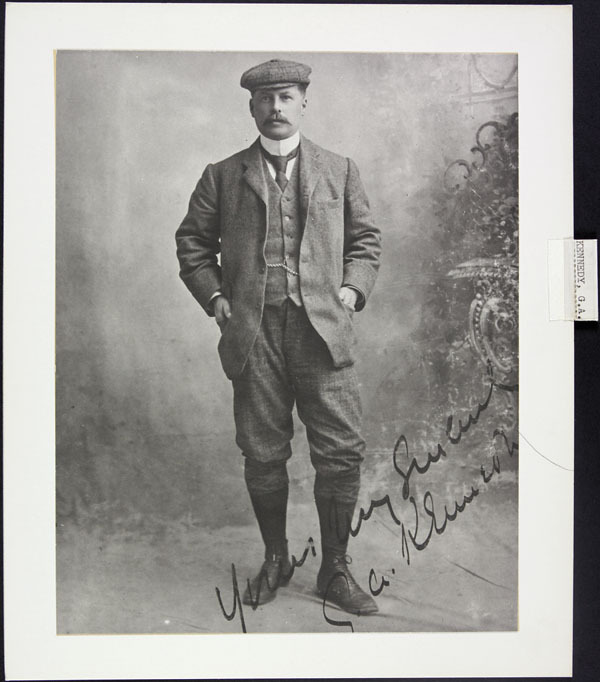

KENNEDY, GEORGE ALLAN, physician, NWMP surgeon, and office holder; b. 16 April 1858 in Dundas, Upper Canada, son of Thomas Kennedy, a boiler-maker, and Jane Allan; m. 19 Sept. 1883 Alice Maude Allen in Cornwall, Ont., and they had a son and a daughter; d. 8 Oct. 1913 in Winnipeg.

George A. Kennedy was educated at the Dundas grammar school and the St Catharines Collegiate Institute. An excellent scholar, he attended the Toronto School of Medicine and graduated from the University of Toronto (mb 1878). He interned at the Hamilton General Hospital before his former dean in Toronto recommended him for a medical position with the North-West Mounted Police, which had come open with the resignation of Richard Barrington Nevitt.

An order in council of 23 Sept. 1878 appointed Kennedy an assistant surgeon with the force beginning 1 October, at an annual salary of $1,000. From that date until his resignation on 30 June 1887 he served primarily at Fort Macleod (Alta) [see James Farquharson Macleod*]. For periods before November 1882 he covered emergencies at Fort Walsh (Sask.); subsequently he had some responsibilities at Fort Calgary (Calgary). In 1882 he was passed over for the senior surgeon’s position in favour of Augustus Jukes, but by all accounts Kennedy was an effective medical officer who enjoyed the frontier.

In 1881 his salary had been raised to $1,200. That half of it was to be paid by the Department of Indian Affairs reflected the time he had spent dealing with epidemics at Cree and Assiniboin camps near Fort Walsh. In a Cree encampment on one day in September 1880 he treated 150 patients for diarrhoea and dysentery, but many, especially children, died. By 1882 his principal objective was the vaccination of children against smallpox.

Within the contexts of the varied circumstances of practice on the prairies and the state of medical understanding, Kennedy’s duties appear to have been routine. Having limited means for treating infectious diseases, he focused on prevention, especially in his assessments of NWMP outposts and divisional centres. He came to believe that the western air was healthy, but that the force undermined this advantage by poorly situating and constructing its barracks. Kennedy advocated replacing buildings that featured inadequate drainage, space, and ventilation, often located in river bottoms, with spacious, better-ventilated structures on well-drained higher ground. Improved conditions were even more important in hospitals, and also in guardrooms for the health not only of the prisoners but of the policemen, who frequently reported sick after guard duty. Kennedy’s special care was reserved for hospital facilities. A highlight was the inclusion of a first-class hospital in the relocated quarters built at Fort Macleod and occupied in 1884.

Often, in isolated situations, standard procedures became daunting challenges for Kennedy. His account in 1880 of a mid-thigh amputation on an Indian boy, including a thorough examination under anaesthetic, drew commendation from a physician who reviewed the report in the 1950s and reflected Kennedy’s evident concern to remain up to date in his practice. He was obliged to make some of his own surgical instruments, and occasionally he was called upon to examine corpses for evidence of cause of death. Cases ranged from a scalped Cree with multiple gunshot and stab wounds to an apparent suicide, where his testimony indicated instead an attack from behind.

Kennedy’s years of varied experience with the NWMP equipped him well for his shift to private practice in Fort Macleod in 1887. The move coincided with the peak of NWMP activity there and the boom ushered in by the Canadian Pacific Railway. Even before leaving the force, Kennedy had been establishing himself in the town, and helping to establish the town, which would be incorporated in 1892. In 1884 he brought in Toronto pharmacist John David Higinbotham to manage the drugstore he had opened, Alberta’s first. The “civic committee” he chaired in 1885–86 organized the construction of a town hall and initiated the Macleod Improvement Company. He continued to be active as a private citizen, sitting on the first executive committee of the Board of Trade, formed in 1888. The high point of his participation seems to have been the mid 1890s, when he served as a school trustee and as an unpublicized editor of the Outlaw (Scotts Coulee), a satiric, independent newspaper issued briefly before the federal election of 1896. Intermittently, Kennedy, an Anglican and a freemason, became involved in the executives of the Macleod Club, the Macleod Turf Association, and the Royal Macleod Golf Club. A founding supporter of the University of Alberta, he sat in its senate (1908–9) and on its board of governors (1911–13).

With respect to Kennedy’s primary dedication to health care – he would practice medicine in Macleod until his death in 1913 – his local, regional, and national commitments intersected. As a member of Fort Macleod’s hospital committee, undoubtedly he had helped secure the ordinance passed in 1887 to incorporate the local hospital. For part of the 1890s he was Macleod’s public health officer. He admonished the town council to upgrade drains, and personally supervised quarantine and treatment operations during epidemics, including the smallpox outbreak of 1892 at the nearby Blood Indian Reserve. As well, he was inspector of hospitals for the North-West Territories (1897–1905) and surgeon for the Crowsnest Pass branch of the CPR (1895–1913).

Kennedy never lost sight of the importance of broader connections, especially to gain medical knowledge. He was president of the Alberta College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1907–8, and had earlier served as a vice-president of the Canadian Medical Association, from 1889 to 1892. In a paper presented at its meeting in Banff in 1889, he drew attention to the healthfulness of southern Alberta’s climate. He joined with other prominent western practitioners in promoting the Dominion Medical Council, to which he was elected in 1913.

G. A. Kennedy clearly embodied professional development in the west. In his report to the NWMP in 1886 he had advocated a systematic analysis of the local fevers that he had been unable to identify conclusively. The same kind of vision animated his last trip eastward, in 1913. He was waylaid in Winnipeg by cancer, but his intention had been to study tuberculosis in Europe in order to specialize in the treatment of that disease with his son, Alan Hugh Neville, in Macleod.

George Allan Kennedy’s account of the last major Indian battle in the Canadian northwest, between the Plains Cree and the Assiniboin in 1870, is printed in J. D. Higinbotham, When the west was young: historical reminiscences of the early Canadian west (Toronto, 1933), 231–38.

Kennedy’s reports as an assistant surgeon with the NWMP appear in Can., North-West Mounted Police, Report (Ottawa), 1879–82 and 1884–86. His 1889 paper on “The climate of southern Alberta and its relation to health and disease” was published in the Montreal Medical Journal, 18 (1889–90): 247–57; it appeared in an abridged version in the American Medical Assoc., Journal (Chicago), 13 (July–December 1889): 376–79. His contributions to medical literature also include “Case of penetrating bullet wound” in Canadian Practitioner (Toronto), 13 (1888): 377–79.

AO, RG 80-5-0-120, no.11830. NA, MG 29, D61: 4534–37; RG 31, C1, Dundas, [Ont.], 1861: 34; 1871, div.2: 44. Royal Canadian Mounted Police Headquarters (Ottawa), Hist. sect., Service file O.38. Lethbridge Herald (Lethbridge, Alta), 1905–13, esp. 9 Oct. 1913. Macleod Gazette (Fort Macleod, Alta), 1882–1900. Canada Lancet (Toronto), 47 (1913–14): 304. Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 3 (1913): 1016. Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Fort Macleod – our colourful past: a history of the town of Fort Macleod, from 1874 to 1924 (Fort Macleod, 1977). H. C. Jamieson, Early medicine in Alberta: the first seventy-five years (Edmonton, 1947). A. O. MacRae, History of the province of Alberta (2v., [Calgary], 1912), 679. H. [M.] Neatby, “The medical profession in the North-West Territories,” Sask. Hist., 2 (1949), no.2: 1–15. J. B. Ritchie, “Early surgeons of the North-West Mounted Police, III: Doctor George Alexander Kennedy,” Calgary Associate Clinic, Hist. Bull., 22 (1957–58): 171–81, 201–10; “George Alexander Kennedy, m.d., 1858–1913,” Canadian Journal of Surgery (Toronto), 1 (1957–58): 279–86. G. D. Stanley, “Medical pioneering in Alberta,” Alberta Hist. Rev. (Edmonton), 1 (1953), no.1: 6–15. L. H. Thomas, “Archival studies: early territorial hospitals,” Sask. Hist., 2, no.2: 16–20. J. P. Turner, The North-West Mounted Police, 1873–1893 . . . (2v., Ottawa, 1950).

Cite This Article

Carl Betke, “KENNEDY, GEORGE ALLAN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kennedy_george_allan_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kennedy_george_allan_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carl Betke |

| Title of Article: | KENNEDY, GEORGE ALLAN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |