Source: Link

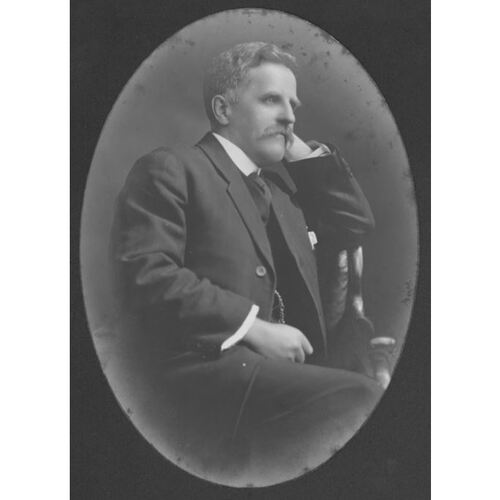

JENKINS, STEPHEN RICE, physician, militia officer, politician, and office holder; b. 12 Nov. 1858 in Charlottetown, son of John Theophilus Jenkins and Jessica Esther Rice; m. 7 Oct. 1886 Ellen Josephine Sweeney, and they had seven daughters and four sons (a daughter and a son did not reach adulthood); d. 15 Sept. 1929 in Charlottetown.

Stephen Jenkins came from a notable Prince Edward Island family – the Anglican clergyman Theophilus Desbrisay* was a great-grandfather – and he would be the fourth in a line of five generations of Jenkins doctors. His father, a Crimean War veteran and the first physician born on the Island to practise there, was elected to the House of Assembly and the House of Commons. In many ways, Stephen Jenkins’s career would mirror his father’s: he would take up medicine, serve in the military, and enter politics. He diverged from family conventions only by leaving the Church of England and converting to Roman Catholicism before his marriage.

Jenkins was educated at St Peter’s Boys’ School in Charlottetown and King’s College in Windsor, N.S. After receiving preliminary medical training from his father, he studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He graduated with honours in 1884 and was then engaged as house surgeon at Blockley hospital in Philadelphia. In 1885 he returned to the Island, where he practised briefly in Tignish before settling in Cardigan. During the smallpox epidemic in the fall of 1885 he was put in charge of a quarantine hospital in Charlottetown. He moved to the city with his family in 1888, the same year he was commissioned surgeon in the 4th Prince Edward Island Provisional Garrison Artillery Brigade. In 1904 he would be made its honorary lieutenant-colonel. He also tried his hand at provincial politics. Defeated in 1900, he was elected in Charlottetown as a Conservative in 1912 and again in 1915. He served as a minister without portfolio during his second term, in the administration of John Alexander Mathieson*, and as chief aide-de-camp to three lieutenant governors. During World War I he entered the Canadian Army Medical Corps, and from March 1915 to April 1919 he was in charge of the Rockhead Military Hospital in Halifax. In 1918 he was instrumental in having a veterans’ hospital established in Charlottetown; it was named in honour of nursing sister Rena Maude McLean* and for a time the medical officer in charge was his son John Stephen.

Taking up active service in the prime of his career probably meant significant financial loss for Jenkins. Recognized as having the largest medical and surgical practice on the Island, he was the only physician to serve at both of its major hospitals; at the time of his death he was senior staff surgeon at the Prince Edward Island Hospital and chief of staff at the Charlottetown Hospital. He normally took hospital rounds and performed surgery in the mornings, and then kept office hours and made house calls. Nights were spent reading medical journals, as he attempted to keep abreast of the latest advances. Later in life, he would take holidays to tour hospitals in London and Vienna.

Jenkins worked steadily to bolster a range of professional organizations. A member of the first Dominion Medical Council, registrar of the Prince Edward Island Medical Council, and a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, he served as president in 1906 of the Maritime Medical Association, chair in 1922 of the Island branch of the American Society for the Control of Cancer, and president in 1928–29 of the Canadian Medical Association. He regularly reported cases at meetings of the provincial medical association, and was active in local committees on cancer research and social hygiene. Concerned with preventive medicine and public health, he helped establish and served as secretary of the provincial Red Cross Society. For a time he was president as well of the Anti-Tuberculosis Society. Jenkins’s professional status also afforded him a role in civic development. He helped foster the local economy as a member of the Charlottetown Club and promoted educational standards and healthy school environments during his 30 years on the city’s school board. A member of the Catholic Mutual Benefit Association and the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity, he founded the Free Dispensary for the Poor and continued the Jenkins Coal Fund, a charity initiated by his father.

This broad involvement did not leave Jenkins much time for his large family – it was Ellen Jenkins who provided the structure in their household. The busy, often absent doctor could still be an indulgent father, one whose kindliness spilled over into his professional role. His daughters recall him, in emergencies, taking patients (and once an entire family) into their home. The demands of work meant that he could be inattentive to his own health. In 1902, for instance, he lost an eye when an infection went untreated. The stresses could also manifest themselves in bursts of temper. It was not uncommon for him, if vexed by some aspect of an operation, to fling a piece of surgical equipment across the room and then carry on. But there was recompense. As he grew older, his flourishing practice allowed him to hire younger doctors to assist him, keep his family in a grand house (Brighton Villa), and spend some leisure time at golf, curling, and tennis.

For Jenkins, “a man of keen intellect and indefatigable energy,” general practice demanded an enormous amount of talent and time, whatever its return. He did not focus on any one specialty, but mastered many. As a colleague would observe in his eulogy, it was through general medicine that he “climbed to the highest pinnacle in his profession.” Jenkins died of pneumonia in 1929 following a brief illness. His passing was peaceful – city council had closed his street so the esteemed doctor could rest. His medical peers regarded him as “the ideal physician,” in true Oslerian tradition, just as his community remembered him as “that perfect citizen.”

A photograph of Stephen Rice Jenkins performing surgery in the operating room of the Charlottetown Hospital is found in PARO, Acc. 2320/32-12.

PARO, P.E.I. Geneal. Soc. coll., family files, Jenkins family, Hilda Jenkins and Margaret Jenkins Taylor, “The Jenkins family: five generations of doctors” (summer 1975). People’s Catholic Cemetery (Charlottetown), Tombstone no.671. Charlottetown Guardian, 16, 18 Sept. 1929. Examiner (Charlottetown), 2 May 1884. Patriot (Charlottetown), 16 Sept. 1929. D. O. Baldwin, “Smallpox management on Prince Edward Island, 1820–1940: from neglect to fulfillment,” Canadian Bull. of Medical Hist. ([Waterloo, Ont.]), 2 (1985): 147–81. Marcia Bruner, “Early practitioners of P.E.I.,” Doctor’s Rev. ([Montreal]), 5 (October 1987): 86–91. Canadian annual rev., 1922. Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal (Toronto), 21 (July–December 1929): 620–21. CPG, 1915–17. Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.3. Maple Leaf (Oakland, Calif.), 22 (December 1929): 383. Past and present of Prince Edward Island . . . , ed. D. A. MacKinnon and A. B. Warburton (Charlottetown, [1906]), 478–79 . I. L. Rogers, Charlottetown: the life in its buildings (Charlottetown, 1983). W. L. Whelan, “The Jenkins of Charlottetown,” Canadian Medical Assoc., Journal, 155 (July–December 1996): 445-47.

Cite This Article

Sasha Mullally, “JENKINS, STEPHEN RICE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jenkins_stephen_rice_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jenkins_stephen_rice_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Sasha Mullally |

| Title of Article: | JENKINS, STEPHEN RICE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |