HÉBERT, NICOLAS-TOLENTIN, priest and colonizer; b. 10 Sept. 1810 at Saint-Grégoire (now part of Bécancour), Lower Canada, son of notary Jean-Baptiste Hébert and Judith Lemire; d. 17 Jan. 1888 at Kamouraska, Que.

Nicolas-Tolentin Hébert received a classical and theological education at the Séminaire de Nicolet and was ordained priest on 13 Oct. 1833 at Quebec City. A curate there until 1840, he became parish priest first of Saint-Pascal, Lower Canada, and then of Saint-Louis in Kamouraska; the latter post he held from 1852 until his death.

It is as a colonizer that Nicolas-Tolentin Hébert deserves attention. In the late 1840s the clergy was endeavouring to stimulate large-scale colonization in Canada East in order to slow down the exodus of its Catholic population to the United States. In support of this effort, the priests of the constituencies of L’Islet and Kamouraska met at Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière) at the end of 1848 and decided to set up the Association des Comtés de L’Islet et de Kamouraska pour Coloniser le Saguenay. They entrusted the responsibility for this undertaking to Hébert who was known for his practical mind and organizational ability.

The association was something of a prototype for the land settlement societies of Quebec in the 19th century. It had the structure of a cooperative, with the parish as the basic unit. Each of the participating parishes (there would be eight in all) had a committee representative of the number of its shareholders. Shares were sold at the unit price of £12 10s. (about $50) but, if parish committees so recommended, the society could accept payment in work; a shareholder could hold no more than three shares. A share entitled its owner to a 100-acre lot. After five years the society was to be dissolved and the properties distributed by a drawing of lots. The society reached its peak in 1851, when 296 shareholders held 360 shares. In theory, the money collected was to be used for the purchase of land, the opening of access routes, and, wherever possible, the partial clearing and building of a house on each lot. There was no requirement that shareholders take possession of their property. In reality, the shareholders were divided into two fundamentally different categories: those (largely from the clergy or the local petite bourgeoisie) who sponsored settlers, and those who were themselves settlers; in 1851 the second group represented only 31 per cent of the membership and held but 20 per cent of the shares. These figures give a striking picture of what the Association des Comtés de L’Islet et de Kamouraska pour coloniser le Saguenay really represented: an alliance of clergy and rural bourgeoisie serving a 19th-century ideology focused on God and the land.

Hébert’s organization was not the first to enter the Saguenay area. In 1846 Jean-Baptiste Honorat*, the superior of the Oblates in the Saguenay, had founded the first colonizing settlement at Grand-Brûlé (Laterrière). A year later the people of La Malbaie founded another at the Rivière aux Sables (Jonquière). In 1848, pushing farther west, two societies attempted to gain a foothold to the east of Lac Saint-Jean: that of Baie-Saint-Paul, in the township of Signay, and another, initiated by parish priest François Boucher, in the adjoining township of Caron. The difficulties encountered by these organizations strongly influenced Abbé Hébert. At Laterrière, settlement had been greatly hampered by the desperate struggle waged by the superior of the Oblates against the brutal methods of capitalists William Price* and Peter McLeod* who headed a vast timber monopoly in the region. Furthermore, the townships of Signay and Caron were doomed to stagnate, if not die, for want of support. Hébert concluded that only an efficient organization could ensure a durable settlement, and also that it was in the interests of any colonizing organization to know how to come to terms with those holding the timber monopoly of the region. After his settlement had begun, confrontations occurred with McLeod’s men who were attempting to strip the association’s land of commercial timber. Hébert succeeded in making Price’s partner see reason, and the latter bought logs and agricultural produce from the society, thus supplying it with some income. Such, in brief, are the factors that ensured the success of the work of his association. Hébert did not, properly speaking, open the Lac Saint-Jean region to settlement, but it was he who broke the terrible isolation of the area and hence cleared the way for colonization to move westwards from the Saguenay.

Throughout the period of its operations, and indeed after its dissolution in 1856 (a few years later than intended), the association was able to rely on the leadership of the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière through Abbé François Pilote. The plan of settlement to be carried out by the association, of which Pilote was the last president, was undoubtedly developed in the college. The society had in Pilote both an effective political mediator and a no less skilful publicity agent. In 1852 he published at Quebec Le Saguenay en 1851 . . . , a work designed to make both the Saguenay area and the society’s activities there known.

On 14 Feb. 1849 an order in council granted the association the townships of Labarre and Métabetchouan near Lac Saint-Jean. The society was to meet the cost of surveying the land; the price of the land was fixed at a preferential rate of 1s. per acre until 1 Jan. 1850, when it would rise to 2s. Early in June 1849, Abbé Hébert explored the area with a view to settlement. His final choice was the township of Labarre. On 21 August the occupation and clearing of the new property started; two years later the settlement had 120 permanent residents.

The greatest obstacle the new settlement had to face was the complete absence of access routes: without a road it was in danger of suffocating. After numerous petitions, the government agreed to release £1,500 (approximately $6,000) for the construction of a regional road to link the Upper Saguenay to Lac Saint-Jean. In 1855, one year after work had begun, the funds were exhausted; the road was finally completed after the dissolution of the society. Distance and transport difficulties were a heavy burden on the finances of the new settlement. Moreover, the association had fallen far short of its promises. In 1855 about 100 of a possible 337 lots were occupied. But, more serious still, the society had accumulated debts of $6,800 with merchants, and the government would only issue property titles en bloc for land occupied either by shareholders or by the settlers they had recruited. Surprisingly the greatest recruiting effort took place after the dissolution of the society although it was not until 1871 that all the lots were occupied. The absenteeism of the shareholders who sponsored settlers was quickly denounced by the new settlers as a serious impediment to the colonization process, and only numerous interventions by Hébert and Abbé Pilote prevented the government from revoking the sale of long-vacant lands.

To facilitate the taking over of the land, Hébert had granted the settlers large credit margins on the purchase of lots and merchandise. In order to wipe out the society’s debt, and particularly to reimburse the shareholders sponsoring settlers for their expenses, Hébert changed all the settlers’ debts into mortgage loans. On 26 Aug. 1857 he gave to the general creditor of the society, Jean-Baptiste Renaud, a Quebec merchant, approximately £1,253 11s. in partial payment of the debt of £1,720 7s. 11d. Nine years later he made over further amounts to the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, which assumed responsibility for the remainder of the debt to Renaud. In this way the affairs of the society were liquidated. Collection of the debts continued until the end of the century and resulted in the ruin of many settlers.

Although Nicolas-Tolentin Hébert’s efforts were not totally successful, they nevertheless made possible a colonizing thrust to the west of the Saguenay. Since 1857 the settlement established in the township of Labarre has borne the name of Hébertville, and in 1925 a monument was erected there in honour of the parish priest Hébert.

Arch. du Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière, Qué.), 38-XIV. BE, Chicoutimi, Lac-Saint-Jean-Est (Hébertville). PAC, MG 24,I81. Qué., Ministère de l’Agriculture, Reg. des lettres, Corr. de N.-T. Hébert. Michèle Le Roux, “La colonisation du Saguenay et l’action de l’Association des comtés de l’Islet et de Kamouraska” (mémoire de des, univ. de Montréal, 1972). François Pilote, Le Saguenay en 1851; histoire du passé, du présent et de l’avenir probable du Haut-Saguenay, au point de vue de la colonisation (Québec, 1852). P.-M. Hébert, “Un Acadien ouvre la vallée du Lac-St-Jean,” Soc. hist. acadienne, Cahiers (Moncton, N.-B.), 3 (1968–71): 224–36.

Cite This Article

Normand Séguin, “HÉBERT, NICOLAS-TOLENTIN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hebert_nicolas_tolentin_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hebert_nicolas_tolentin_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Normand Séguin |

| Title of Article: | HÉBERT, NICOLAS-TOLENTIN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1982 |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |

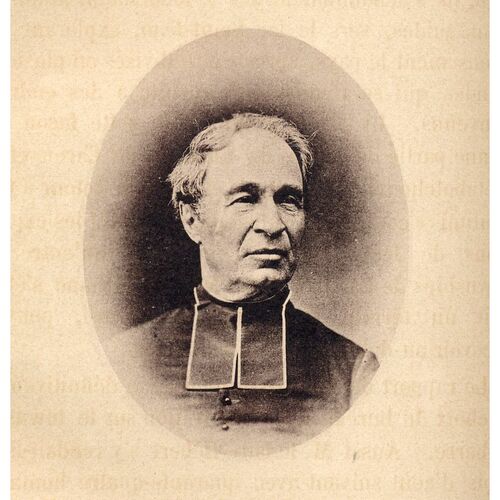

![Le Curé N.-T. Hébert] [image fixe] Original title: Le Curé N.-T. Hébert] [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.4776.jpg)