Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

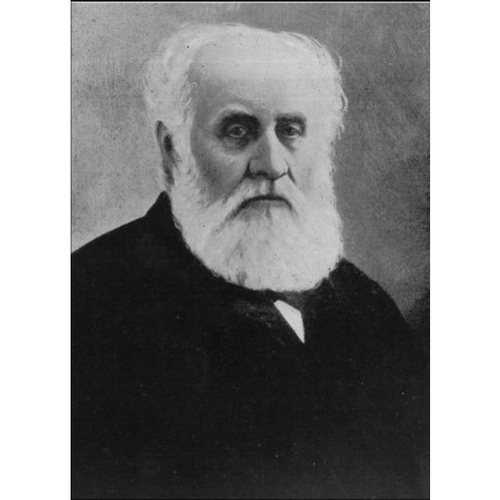

GOODERHAM, WILLIAM, distiller, businessman, and banker; b. 29 Aug. 1790 at Scole, Norfolk, England, second son of James and Sarah Gooderham; m. Harriet Tovell Herring, and they had eight sons and five daughters; d. 20 Aug. 1881 at Toronto, Ont.

When William Gooderham was 12 years old he left his father’s farm in Norfolk to work in the London office of his mother’s brother, an East Indies trader. During the Napoleonic wars he joined the Royal York Rangers and saw action in the capture of Martinique in 1809 and Guadeloupe in 1810. Before he was 21 he was invalided home after contracting yellow fever. Gooderham became a recruiting officer for the duration of the war, and thus acquired the means both to pay off an £800 mortgage on his father’s farm, which he was soon to inherit, and to secure a modest income for himself. He became a gentleman farmer, although his estate suffered from the general decline in values of agricultural property after the war.

In 1831 Gooderham’s brother-in-law, James Worts, began a large immigration of their two families to Upper Canada. Worts established himself as a flour miller at the mouth of the Don River near York (Toronto) and began construction of a windmill. In 1832 Gooderham brought over to York a company of some 54 persons: members of his own and of Worts’s family, as well as servants and 11 orphans. Gooderham invested the £3,000 which he had brought with him in Worts’s milling business and the two brothers-in-law formed the partnership of Worts and Gooderham. It ended with Worts’s death in 1834. Gooderham continued the firm but changed its name to William Gooderham, Company.

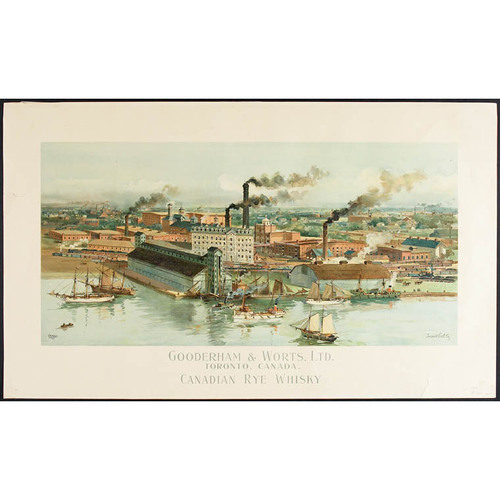

In 1837 he added a distillery to make efficient use of surplus and second-grade grain. Four years later he introduced gas for illumination and converted the entire plant from wind- to steam-power. Shipments on consignment to Montreal in the early 1840s illustrate his growing interests in the harbourfront area and in distant markets. In 1846 the firm built its own wharf and by the 1860s owned schooners on the Great Lakes. His nephew, James Gooderham Worts, had joined him as a full partner in 1845 and the firm’s name was then changed to Gooderham and Worts. During the 1860s and 1870s it enjoyed a pre-eminence in Toronto’s industry, transportation, and finance, as well as on the stock exchange, and in the council and the board of arbitration of the Toronto Board of Trade.

The complex of buildings owned by Gooderham and Worts, designated the Toronto City Steam Mills and Distillery in 1845, grew to become an industrial show-place and made its owners the city’s largest taxpayers. A major expansion was begun in 1859 with a new, five-storey distillery built under the direction of Toronto architect David Roberts and with local suppliers. It was acknowledged as the largest distillery in Canada West: in 1861 it could produce 7,500 gallons of spirits in a day and the firm had begun exporting to the English market. In early 1862 the costs of new buildings, which included storehouses and an engine house, and of equipping the old windmill with modern machinery were estimated at $200,000. A brick malthouse was later added. After 1862 the windmill was used for further distilling the firm’s premium brands, “Toddy” and “Old Rye,” which enjoyed both an English market and large sales in Canada East, as well as “common whiskey” which was popular in Canada West. A spectacular fire destroyed a storehouse and a lumber pile and gutted the interior of the main milling and distillery building on the evening of 26 Oct. 1869, causing approximately $100,000 worth of damage. The company was not covered by insurance. Undeterred, Gooderham and Worts rebuilt, and their business continued to grow. In 1874–75 the company produced over 2,000,000 gallons, or one-third the total amount of proof spirits distilled in the country. By the late 1870s, Gooderham and Worts, in common with other Canadian distillers, had withdrawn from the English market and had turned increasingly to selling grain alcohol for the manufacture of such products as vinegar and methylated spirits, as well as the scent “Florida Water.” Although Gooderham and Worts delegated direct management and some degree of ownership in the 1860s and 1870s, they were primarily responsible for the success of the firm.

Visitors to the Gooderham and Worts establishments after 1861 were struck by their massive size, by their cleanliness, by the fully automatic milling machinery which further distinguished the operation from most others in the province, and by the shelters for the livestock alongside the distillery. Just as the distillery had grown out of the mill, a livestock operation, begun in the 1840s, was an offshoot of the distillery business. Gooderham first raised pigs and then cattle, fattened on the nutritious swill that was a by-product of distilling. A dairy herd numbering 22 in 1843 grew into a dairy and beef operation which by 1861 was fattening about 1,000 animals a year, but at that time the herd was probably no longer owned by Gooderham and Worts. When improved transportation opened an English market, only beef was produced and by the end of the decade there were sheds for 3,000 animals near the distillery. Farms in Peel County near Streetsville and Meadowvale (both now part of Mississauga), listed among Gooderham’s assets in 1881, may have been used to raise supplementary feed.

In 1845 Gooderham and Worts had taken a 14-year lease on flour mills at Norval, Halton County, and they invested in a woollen and linen mill at Streetsville some time before January 1868, when it burnt down. At Gooderham’s death, the firm had mills and general stores at Pine Grove, on a branch of the Humber River, and at Streetsville and Meadowvale. They imported corn for the distillery from the western states, advertised locally for rye (which was, however, largely imported), oats, and barley, and looked to the hinterland of Toronto for supplies of grain.

In the expansion of their facilities after 1859, Gooderham and Worts included a siding to the Grand Trunk Railway large enough to hold 14 cars, and they were to be prominent among Toronto businessmen interested in the narrow gauge railways promoted by George Laidlaw, a former employee. The partners’ interest in railways grew naturally out of the needs of their mills and of the Toronto flour-mill and distillery complex. In 1870, on terms favourable to themselves, they advanced a loan large enough to give the bonds of both the Toronto, Grey and Bruce and the Toronto and Nipissing railways a market value. Thereafter their influence increased in the operation of the two lines, especially the Toronto and Nipissing of which William Gooderham Sr had become a provisional director upon its incorporation in 1868. Even before William Gooderham Jr replaced John Shedden* as president of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway Company in 1873, the Gooderham interests were the railway’s main customer, and the Toronto terminal of this line was established conveniently near the distillery and cattle sheds. Although family control of a railway built with much public funding did not escape criticism, defenders of the line pointed to the need for Gooderham’s capital to launch the enterprise and to finance its chief activity, which involved buying cordwood in the north and storing it to season before transporting it for sale in the city.

When Gooderham became president of the Bank of Toronto in 1864, a post he held until his death, he embarked on the last of several careers. Gooderham and Worts was the only firm in the Millers’ Association of Toronto, which obtained a charter for the bank in 1855. Until he took over as president, Gooderham left Worts to look after the partners’ interests in the bank. Although he had also been a director of the Bank of Upper Canada in 1860, Gooderham probably had viewed this role as serving his other interests more than those of banking. The Bank of Toronto was fortunate in having George Hague as cashier (general manager) for 13 of the 17 years of Gooderham’s presidency. Nevertheless, the bank’s combination of conservative investment policy with internal efficiency and innovative management bore the mark of Gooderham’s stamp. Under him the bank achieved an enviable reputation for stability which brought it a growing share of the business from the staple industries. Its stocks remained at a relatively high price, even during the recession in the 1870s. The Bank of Toronto was also a leader in expounding the interests of Ontario banks and its directors saw several of the operating principles of their managers, notably the maintenance of an unusually large reserve, incorporated into dominion regulations established by the bank acts of 1870 and 1871 [see Sir Francis Hincks]. As it must have reflected his views on the relative value of banks and savings companies, the inventory of Gooderham’s estate provides an interesting footnote to his banking career: he held shares worth $42,000 in the Bank of Toronto as opposed to $122,000 in loan and savings companies, $90,000 of this sum in the Canada Permanent and $32,000 in the Western Canada Loan and Savings companies.

Although his conservative views were well known, Gooderham avoided the public eye, and even if he was on the first publicly elected school board in 1850, his only real venture into politics was as city alderman for St Lawrence Ward in 1853 and 1855. He chaired the committee on wharves and harbours which accepted Casimir Stanislaus Gzowski*’s tender, later overturned, to build the Esplanade development. A staunch evangelical Anglican, Gooderham was a leading member of Little Trinity Church (which was near the distillery) and a warden from 1853 to 1881. He was a lifelong freemason, and served as president of the York Pioneer Society from 1878 to 1880. His charitable activities were both personal (he took a growing number of orphans under his protection) and institutional. He represented the board of trade on the trust of the Toronto General Hospital, and along with Worts and William Cawthra* he contributed the $113,500 needed to build a new wing for patients with infectious diseases.

In the last three or four years of his life, Gooderham turned much of his business over to his third son, George*, who became a full partner in Gooderham and Worts before his father died. His eldest son, William, president and managing director of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway from 1873 to 1882 after an inglorious career in other businesses, died in 1889; his second son, James, had been killed in an accident on the Credit Valley Railway in 1879. Three other sons, Henry, Alfred Lee, and Charles Horace, were employed in branches of the family concerns. The Reverend Alexander Sanson of Little Trinity Church eulogized Gooderham as a type of patriarch.

Even after providing for his children, Gooderham left an estate which amounted to approximately $1,550,000 at first valuation. Obituaries stressed the breadth of his influence in the business community and his contribution to the city’s growth from a town of “three or four thousand inhabitants, and little wealth” to the metropolis in 1881. Gooderham built his empire by combining the principle of dealing in articles of widespread consumption with a sensitivity, which he retained as he grew older, to the opportunities offered by new techniques and new markets. In the fluctuating marketplace of Toronto in the mid 19th century, this combination proved highly successful.

MTL, Biog. scrapbooks, VII: 481; XXIX: 25; Toronto scrapbooks, VII: 127; XII: 41. York County Surrogate Court (Toronto), no.3236, will of William Gooderham, 9 Sept. 1881 (mfm. at AO). Bank of Toronto, Reports and proc. of annual meetings (Toronto), 1857–81. Can., Parl., Sessional papers, 1876, III: no.3. “Canadian railways, no.XXV: Toronto and Nipissing Railway,” Engineering; an Illustrated Weekly Journal (London), 28 (July–December 1879): 295–98. Toronto Board of Trade, Annual report . . . (Toronto). 1860–63; Annual review of the commerce of Toronto . . . , comp. W. S. Taylor (Toronto), 1867, 1870; Annual statement of the trade of Toronto . . . , comp. J. M. Trout (Toronto), 1865. Daily Mail and Empire, 23 Oct. 1933. Globe, 7 Feb. 1862, 22 Aug. 1881, 21 June 1882, 6 March 1885. Monetary Times, 1869–83. Toronto Daily Mail, 22 Aug. 1881, 21 June 1882. Canadian biog. dict., I: 62–70. Chadwick, Ontarian families, I: 154–57. Dominion annual register, 1882. Masters, Rise of Toronto. Middleton, Municipality of Toronto. Robertson’s landmarks of Toronto. Joseph Schull, 100 years of banking in Canada: a history of the Toronto-Dominion Bank (Toronto, 1958). E. B. Shuttleworth, The windmill and its times; a series of articles dealing with the early days of the windmill (Toronto, 1924). Shortt, “Hist. of Canadian currency, banking and exchange: some individual banks,” Canadian Banker, 13: 11, 184–91.

Cite This Article

Dianne Newell, “GOODERHAM, WILLIAM (1790-1881),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gooderham_william_1790_1881_11E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gooderham_william_1790_1881_11E.html |

| Author of Article: | Dianne Newell |

| Title of Article: | GOODERHAM, WILLIAM (1790-1881) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1982 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |