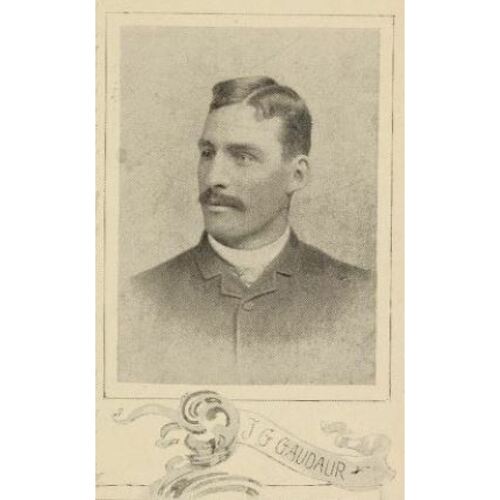

GAUDAUR, JACOB GILL, oarsman, hotelier, boat-rental operator, and fishing guide; b. 4 April 1858 in Atherley, near Orillia, Upper Canada, son of Francis (François) Antoine Gaudaur, a bridge tender, and Jeanette (Janet, Jennet, Jessie) B. Gill; m. first 7 Nov. 1883 Cora M. Coons (1859–94) in St Louis, Mo., and they had a daughter; m. secondly 1894 Ida Elizabeth Harris (1867–1911) in Orillia, and they had at least five sons, one of whom died in infancy, and two daughters; m. thirdly 14 Jan. 1913 Alice Grace Hemming (1880–1964) in Halifax, and they had a son and four daughters, one of whom was stillborn; d. 11 Oct. 1937 in Orillia and was buried there in St Andrew’s–St James’ Cemetery.

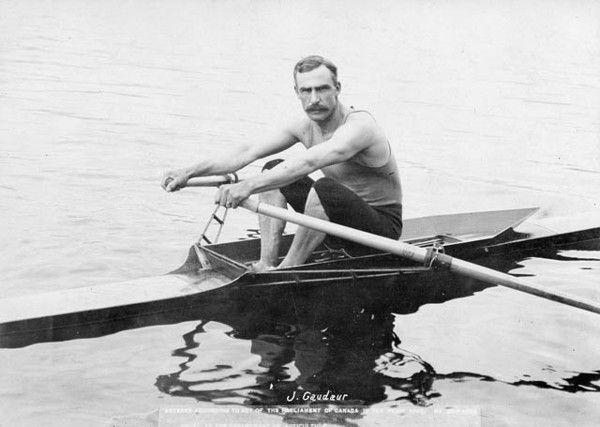

Jake Gaudaur was a teenager when he was encouraged to take up professional rowing by Edward Hanlan*, the Toronto-based world champion who dominated the sport during its heady days in the late 19th century. At 6 feet 2 inches in height and 175 pounds at his peak weight, Jake was taller and heavier than his mentor but had little of the quick success and none of the flamboyant showmanship of “the boy in blue.” Gaudaur did have a huge appetite for hard work and extraordinary determination and persistence. After years of trying, he would emerge from Hanlan’s shadow to become the premier sculler of his generation: in 1896, at the age of 38, he won the world singles championship that Hanlan had lost 12 years earlier. In 1939 his friend Stephen Butler Leacock* would proclaim, “If you don’t know the name of Jake Gaudaur it only means that you were born fifty years too late.… Jake Gaudaur was a hero to millions who had never seen him.”

Gaudaur (pronounced “Good-Oar,” according to Leacock) was of Métis and Scottish ancestry. His grandparents had been among the first settlers in Orillia, and Jake was born and raised at the nearby Narrows between Lake Simcoe and Lake Couchiching. Growing up, he spent most of his time in and around boats. The Gaudaurs were a family of athletes. Jake’s brother Francis Ford was a successful rower, and four cousins won sporting championships, two in the shot put (George Reginald and Joseph Woods Gray), one in double sculls (John Gray), and another as an all-rounder (Harry Gill). Jake began racing as an amateur, pairing in doubles with his brother Frank. In 1875 Hanlan invited Jake to substitute for him in a $500 challenge race against Hugh Wise in a skiff, a type of boat in which Hanlan no longer rowed, on Lake Couchiching. After Jake won easily, Hanlan took him under his wing and promoted the Gaudaur brothers in professional double sculls races for several years. Until the early 1880s, however, Jake competed only occasionally; it was then that Toronto hotelier Richard Dissette agreed to pay his living expenses so that he could devote himself full-time to sport. He subsequently trained twice a day, rowing seven to ten miles a session. He would later recall: “I was always a great believer in hard work and plenty of sleep. While I was in training I did not smoke or drink except for an occasional pint of champagne which I found beneficial. When I was not rowing I was out in the bush carrying packs.” Gaudaur was soon racing all over North America, in regattas and one-on-one match events, in singles, doubles, and the occasional fours, often in the same regatta, partnering with whomever was available. Most races were 3 miles or longer, a much greater distance than the 1 mile and 427 yards that would later become the Olympic standard. After 1886 he operated out of Creve Coeur, near St Louis, until he moved to Toronto, where he was living by 1891. He would race more than 200 times in his career.

Initially, Gaudaur often faded in the big events. Even after he won the American championship in 1886, defeating American John Teemer in Pullman (Chicago), doubts about his stamina persisted. When he sought a match for $5,000 and the world championship against Hanlan’s conqueror, Australian William Beach, the Montreal Gazette opined that Gaudaur had yet to prove his superiority even over Canadian oarsmen. Beach accepted his challenge, and on 18 Sept. 1886 they raced on the Thames River in London, England. It was one of the closest contests of its kind ever held. In front of spectators lined rows deep on each bank, the two men traded the lead over the 4-mile, 374-yard course between Putney and Mortlake, maintaining a pace so exhausting that they both had to stop periodically to catch their breath. Gaudaur held a narrow advantage late in the race, but Beach overtook him near Barnes Bridge and held on to defend his title.

After this loss Gaudaur was rarely beaten. In 1887, on Lake Calumet near Chicago, he defended his American championship against Hanlan and won $5,000. In the years that followed, he usually defeated every major oarsman except for Torontonian William Joseph O’Connor*. Races could be bitterly contested on and off the water. In September 1889 Gaudaur, after being violently ill, complained that he had been drugged before a showdown with Teemer in McKeesport, Pa. Gaudaur managed to win anyway, but his coach was accused of rowing onto the course and blocking Teemer’s path. A brawl ensued between supporters of the two men, and the referee decided to call the race a draw.

Gaudaur repeatedly lowered the world record for the three-mile course with a turn; his ultimate time of 19:01.5, set on 17 May 1894 at a regatta in Austin, Tex., was never bettered. With American George Hosmer, he had taken the world doubles championship from Hanlan and O’Connor in 1892. Not until 1896, however, did he get another opportunity to win the world singles championship, by then held by Australian James Stanbury. The race took place on the Putney to Mortlake course on 7 September, and Gaudaur won by 45 seconds, a commanding margin, with a time of 23:01. He returned to Canada in great triumph. Toronto gave him a civic reception, and in Orillia he was honoured with a steamboat parade, a gold watch, and a tribute from the mayor. Gaudaur held the title for five years before losing it, on 7 Sept. 1901, to Australian George Towns in Rat Portage (Kenora), where Jake was then living. Afterwards, according to authors Sydney Francis Wise and Douglas Mason Fisher, “Gaudaur went out like a champion. Rowing over to Towns, he took off his cap to him and said, ‘George, the best man won.’” He never raced again.

In retirement Jake Gaudaur ran a hotel in Sudbury, where, according to Stephen Leacock, “thousands of people spent five cents on a drink just to say they had talked with Jake Gaudaur.” After he had made “his modest pile” there, as Leacock put it, Gaudaur returned home and became a boat-rental operator and fishing guide at the Narrows. In September 1936 his fellow citizens erected a plaque to thank him “for bringing more fame to Orillia than any other sportsman in this town’s history.” He died of lymphatic leukaemia on 11 Oct. 1937 at the age of 79. He was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1956. His son Jacob Gill*, whom he had trained as a rower, would keep the family name in the headlines as a professional football player, president and general manager of the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, and commissioner of the Canadian Football League.

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame (Calgary), Jake Gaudaur Sr. file. Gazette (Montreal), 12 Oct. 1937. Globe, 18 May 1894, 8 Sept. 1896. Globe and Mail, 12 Oct. 1937. Pittsburg Dispatch (Pittsburgh, Pa), 14, 15 Sept. 1889. Times (London), 20 Sept. 1886, 8 Sept. 1896. Toronto Daily Star, 14 Jan. 1913. S. A. Brooks, “An athletic biography of a champion Canadian sculler, Jacob Gill Gaudaur 1858–1937” (ma thesis, Univ. of Western Ont., London, 1981). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898, 1912). R. S. Hunter, Rowing in Canada since 1848 … (Hamilton, Ont., 1933). S. [B.] Leacock, “Bass fishing on Lake Simcoe with Jake Gaudaur,” in his Too much college or education eating up life: with kindred essays in education and humour (New York, 1939), 241–55. S. F. Wise and D. [M.] Fisher, Canada’s sporting heroes (Don Mills [Toronto], 1974).

Cite This Article

Bruce Kidd, “GAUDAUR, JACOB GILL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 17, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gaudaur_jacob_gill_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/gaudaur_jacob_gill_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Bruce Kidd |

| Title of Article: | GAUDAUR, JACOB GILL |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2023 |

| Year of revision: | 2023 |

| Access Date: | December 17, 2025 |