Source: Link

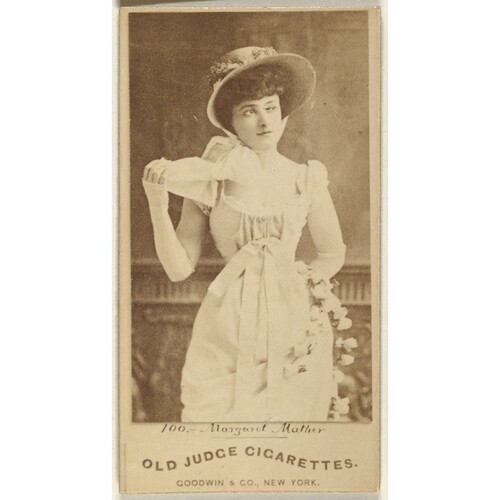

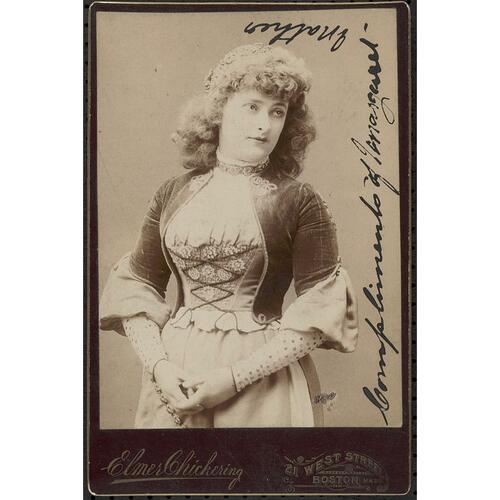

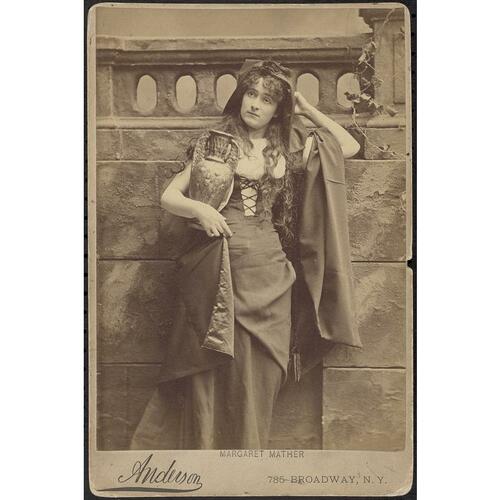

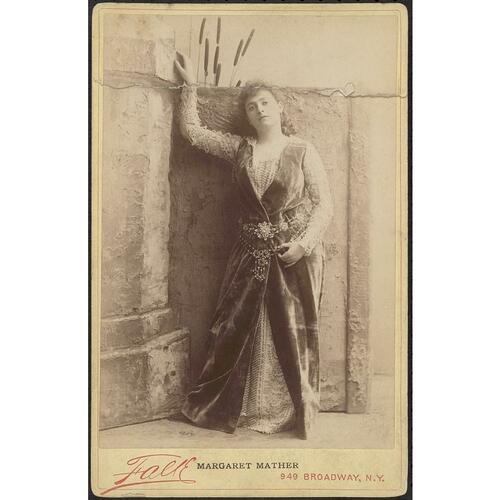

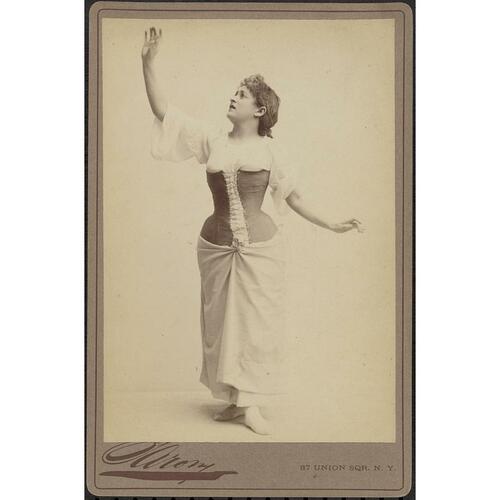

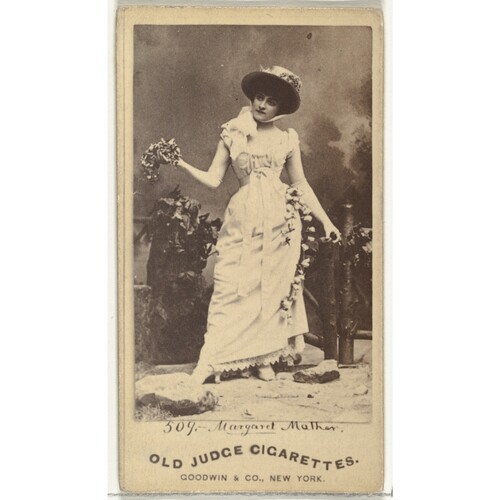

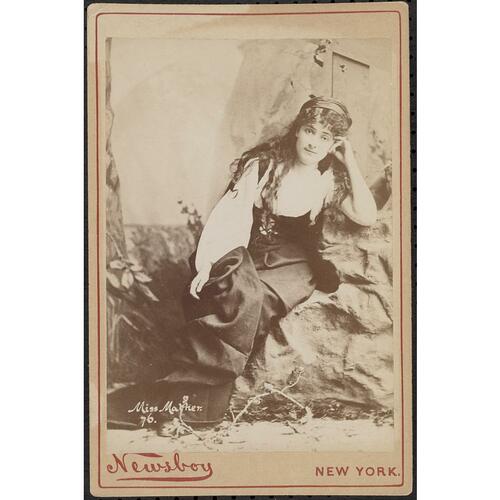

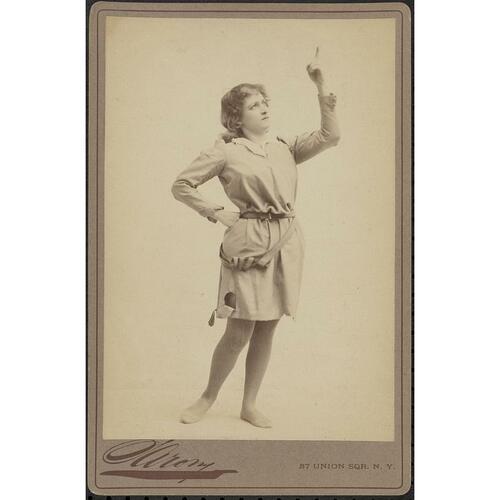

FINLAYSON, MARGARET (Haberkorn; Pabst), known as Margaret Bloomer and Margaret Mather, actress; b. 21 Oct. 1859 in Tilbury East Township, Upper Canada, daughter of John Finlayson, farmer and mechanic, and Ann Mather; m. first 15 Feb. 1887 Emil Haberkorn in Buffalo, N.Y.; m. secondly 26 July 1892 Gustav Pabst; she had no children; d. 7 April 1898 in Charleston, W.Va., and was buried in Detroit.

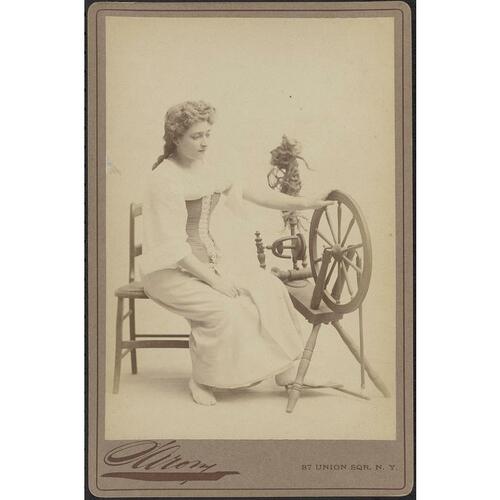

Margaret Finlayson was taken to Detroit around the age of five with her three brothers and two sisters, and spent her childhood in impoverished surroundings. Since her Scots father was frequently unemployed, she was obliged between the ages of 10 and 14 to sell the Detroit Free Press in the streets. Her waif-like existence continued when she left home to wash dishes in a hotel. Attempting suicide one night by throwing herself into the Detroit River, she was rescued and subsequently placed, according to Henry James Morgan*’s Types of Canadian women, “in a position to cultivate her great natural gifts for the stage.” Presumably money was provided for training and living expenses. This raw but strikingly pretty 19-year-old redhead assumed the name Margaret Bloomer and headed for New York to enter the theatre.

Between 1879 and 1881 she studied with George Edgar, an actor-elocutionist who was supported by a company recruited mainly from his pupils. He channelled her talent into a series of Shakespearian heroines. While playing Cordelia in King Lear, she was noticed by manager J. M. Hill and placed under contract. For a year she was removed from public scrutiny and housed with drama critic John Habberton of the New York Herald to be introduced to literature, trained in deportment, and “mentally scrubbed down.” Hill then arranged a carefully calculated series of private recitations before critics and friends, thus arousing curiosity in her talent. On 28 Aug. 1882 she made her successful début at McVicker’s Theatre, Chicago, playing Shakespeare’s Juliet, a role with which she became indelibly identified. About this time, she adopted the maiden name of her English-born mother, who travelled with her. For another three years Hill organized road-tours of Romeo and Juliet, including performances in Canada in Toronto (December 1883), London (December 1884), and Montreal (May 1885), cities that were part of North America’s touring circuits. Her orthodox repertoire was expanded to include Rosalind in As you like it and the title roles in John Augustin Daly’s Leah the forsaken and Bulwer-Lytton’s The lady of Lyons. These starring vehicles were similar to those chosen by Mary Anderson, Julia Marlowe, and Adelaide Neilson, contemporary rivals with whom Mather wished to be compared. Finally, she was brought to Hill’s Union Square Theatre in New York, amidst an extensive advertising campaign.

She opened as Juliet on 13 Oct. 1885 and took Broadway by storm. Her much publicized revival of Romeo and Juliet ran for 84 consecutive performances, establishing an American record. Audiences thrilled to the unexpected physical quality and harshness of her characterization; in the potion scene she rolled down a flight of stairs after taking the drink. However, critics writing later were less kind. Much of her reputation had been “deliberately manufactured,” according to her obituary in the New York Times. To George Clinton Densmore Odell, chronicler of 19th-century theatre in New York, her Juliet had a “synthetic excitement” and lacked the “breeding expected of a daughter of the Capulets.” He praised her “natural force,” “powerful voice,” and “ambition and courage” but found her accent “provincial.” The Times obituary also noted her “defective delivery . . . and her habitual crudities of speech.” In comparison to Mary Anderson’s handling of Juliet, Mather’s was dismissed by Odell as “tawdry and violent to a degree.” This violence was vividly described by fellow actor Otis Skinner, who once saw her coming away from a scene in Leah the forsaken, “waves of hysteria passing over her; her fingers would snap; nervous laughter on her lips, and the pupils of her eyes dilating to an entire blackness. . . . The condition would last five or ten minutes, then she would come out of it weak as a kitten.”

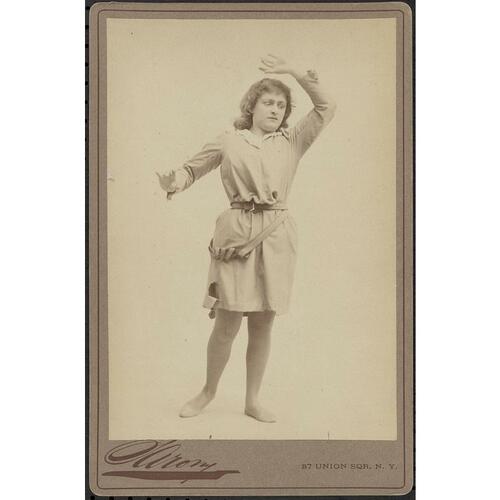

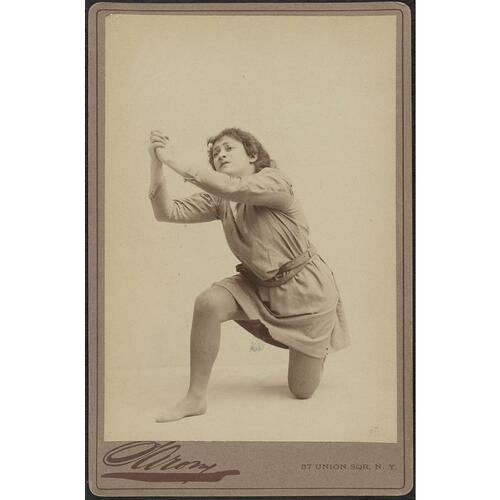

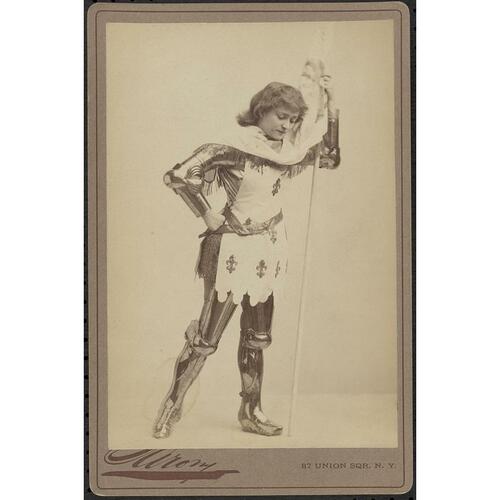

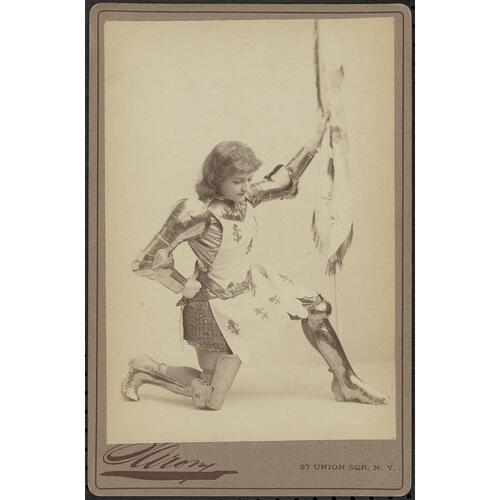

Mather’s private life was equally turbulent. In 1887, unknown to manager Hill, she married Emil Haberkorn, the orchestra leader at the Union Square Theatre. When he asked to see Mather’s account, Hill refused, prompting a lawsuit that resulted in her release from her lengthy contract. Haberkorn served as her manager until 1891, during which time her romantic repertoire was further expanded. In 1890 she made a sincere effort to be recognized as a great tragic actress by playing in William Young’s English adaptation of Jules Barbier’s Jeanne d’Arc, in which Sarah Bernhardt had achieved success. Though handsomely staged and with music by Charles Gounod, the production was found to be “heavy and slow,” Odell recalled. It was quickly dropped. Like so many expatriate performers Mather remained loyal to her roots, touring frequently in Canada (Montreal in 1890 and Winnipeg and Hamilton in 1892–93).

On 2 July 1892 Mather obtained a divorce from Haberkorn on the ground of desertion – they had separated the previous year. (One of her Romeos, Otis Skinner, assumed the managerial mantle for a few years.) Less than a month after the divorce Mather married Gustav Pabst, a son of the Milwaukee brewing magnate. This marriage, too, was an unhappy one; in October 1895 she reputedly horsewhipped Pabst on a Milwaukee street. He later sued for divorce, alleging cruelty, and reportedly gave her $100,000 not to contest the suit.

After their divorce on 19 Oct. 1896 she returned to the stage, mounting a lavish, $40,000 revival of Shakespeare’s Cymbeline at Wallack’s Theatre in New York. She subsequently took the play on tour through the United States and Canada, along with Romeo and Juliet and other plays from her repertoire. The Cymbeline tour was an arduous undertaking, for not only was the company hers but she performed every night. In the part of Imogen she had a role better suited to her talents. The New York Times later said it was “probably her most intelligent, sensible, and edifying achievement.” Hector Willoughby Charlesworth*, who saw her performance in Toronto in 1897, called her Imogen “touching” but tended to agree with others that her Juliet “seemed to lack lightness of touch and inspiration.” The reviewer in Berlin (Kitchener) was less polite: her “Juliet has grown older and plumper with the years.” Mather did not present Cymbeline in Berlin because there were too few advance subscriptions for this unfamiliar drama but she had offered it in Montreal. Playing Imogen there on 27 May 1897 she calmed an audience during an earthquake tremor. In early April 1898 she had to break in four new actors and take on extra responsibilities when her road-manager took ill and left the company. On 6 April, during a performance of Cymbeline in Charleston, fellow actors noticed that she was omitting lines and behaving oddly. She collapsed on stage and never regained consciousness, dying the following afternoon from convulsions caused by Bright’s disease.

The troubled career of Margaret Mather was not to end peacefully. Her body was taken for burial to Detroit, where a crowd of at least 5,000 seethed around the mortuary chapel of Elmwood Cemetery. Otis Skinner, a pallbearer, observed that the throng had been promised a view of the body attired as Juliet. When this was denied, the mob, out of control, trampled over “hallowed mounds . . . and by the time we reached the final resting-place of Margaret Mather’s body, much of the spruce lining of the grave had been stolen for souvenirs.”

Skinner informs us that Mather had not been a communicative person. “Behind her silence was a chaos of fancy, ambition, sympathy, generosity, jealousy, timidity – all ill-adjusted and treading each upon the other’s heels.” In her acting she had “impulse, power, intensity, but it was all unrestrained.” Born on the wrong side of the tracks and, in Skinner’s opinion, “animated by a never-ceasing desire to do something – to be somebody,” Margaret Mather aspired to tragic greatness but, ultimately, she remains only a colourful theatrical memory.

NA, RG 31, C1, 1861, Tilbury East. Otis Skinner, Footlights and spotlights; recollections of my life on the stage (Indianapolis, Ind., [1924]), 192–98. New York Times, 8 April 1898: 7. Times (Tilbury, Ont.), 8 April 1898. Catalogue of dramatic portraits in the theatre collection of Harvard College Library, comp. L. A. Hall (4v., Cambridge, Mass., 1930–34). The Marie Burroughs art portfolio of stage celebrities . . . (Chicago, 1894). Types of Canadian women (Morgan). Franklin Graham, Histrionic Montreal; annals of the Montreal stage with biographical and critical notices of the plays and players of a century (2nd ed., Montreal, 1902; repr. New York and London, 1969), 276, 278–79. G. C. D. Odell, Annals of the New York stage (15v., New York, 1927–49), esp.12–15.

Cite This Article

David Gardner, “FINLAYSON, MARGARET (Haberkorn; Pabst), known as Margaret Bloomer and Margaret Mather,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 31, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/finlayson_margaret_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/finlayson_margaret_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | David Gardner |

| Title of Article: | FINLAYSON, MARGARET (Haberkorn; Pabst), known as Margaret Bloomer and Margaret Mather |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | December 31, 2025 |