Source: Link

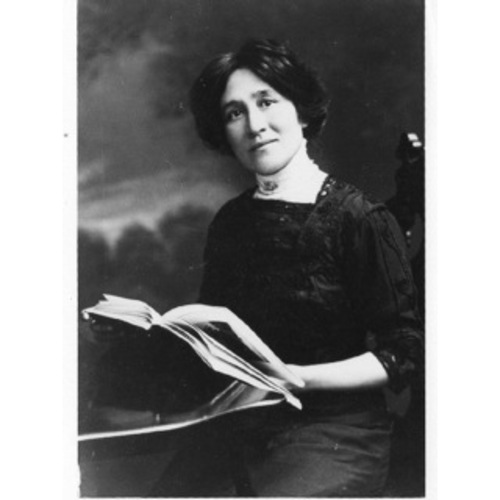

EATON, EDITH MAUD (she often used the pseudonym Sui Sin Far), stenographer, journalist, and author; b. 15 March 1865 in Prestbury, Cheshire, England, daughter of Edward Eaton and Grace Trefusis; d. unmarried 7 April 1914 in Montreal.

The eldest daughter of an English father and an English-educated Chinese mother who had met in Shanghai, Edith Eaton was the second of 14 children. She spent her early childhood years in England and emigrated with her family, first to Hudson, N.Y., where they lived briefly, and then to Montreal, where they settled in 1872 or 1873. Edith was then seven or eight. By the time of their arrival in Canada the family had clearly suffered financial set-backs. From the nursemaid and private school of England, Edith was reduced to augmenting the family’s income by selling her father’s paintings and her own lace work door to door. The family was, in her words, “very poor.” They moved every one to three years. Until 1889 her father held positions as a clerk or occasionally as a bookkeeper; for his remaining years he made his living as an artist.

Suffering from an enlarged heart, an outcome, it seems, of rheumatic fever, Edith was recognized as the delicate member of the family. Her first post was that of stenographer. She worked initially in offices in Montreal and then freelanced for local newspapers. About 1898 she moved to the west coast of the United States, on the advice of her doctor after another attack of rheumatic fever. She thus began a peripatetic existence which was to continue for the next eight to ten years, moving back and forth between Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle, with trips to Montreal. In 1909 Eaton returned east, to Boston, where until 1913 her work was published in the New England Magazine and the Independent. Increasing ill health brought her back to her family in Montreal during the last years of her life.

Puzzled as a child by the prejudice she encountered, Eaton remained throughout her life concerned with the lot of the Chinese in North America. Her first opportunity to learn of her mother’s people came with early assignments to write of events in the Chinese community for Montreal newspapers. The assignments increased her knowledge and support of Chinese causes. “I give my right hand to the Occidentals and my left to the Orientals, hoping that between them they will not utterly destroy the insignificant ‘connecting link,’” she wrote in a brief memoir of her life.

As she moved up and down the west coast, making her living as a stenographer, Eaton became familiar with the Chinese communities in San Francisco, Seattle, and Los Angeles, and wrote articles and stories on the situation of Chinese and Eurasians, using the Chinese pseudonym Sui Sin Far (water fragrant flower, or narcissus). She realized that she could write realistically from within the community, countering the prejudices and mistaken views she met with and read in stories by Occidentals. To the associate editor of the Century Illustrated Magazine (New York and London) she wrote, “I try to depict as well as I can what I know and see of the life of the Chinese people in America. I have read many clever and interesting Chinese stories by American writers, but they all seem to me to stand afar off from the Chinaman – in most cases treating him as a ‘joke.’” She wrote movingly of Eurasians like herself, who did not belong to either community, and of Chinese women, who were often isolated, without opportunity to adjust to an alien culture or to learn its language. She effectively criticized social and political prejudice prevalent against Chinese immigrants. In some stories she dramatizes their problems, directly attacking contemporary prejudice and unthinking bureaucracy. In others, she employs irony and humour. In two stories, she uses the Chinese immigrant Mrs Spring Fragrance as a witty and compelling observer of and commentator on east-west cross-cultural encounters. For the first time in North America, stories of this oppressed ethnic minority were written from within that group.

Eaton’s work was published widely, appearing in periodicals as diverse as Walter Blackburn Harte’s literary magazine Lotus (Kansas City, Mo.) and the popular family periodical Youth’s Companion (Boston) and including Delineator (New York), Hampton (New York), Good Housekeeping (New York), Land of Sunshine (Los Angeles), Chautauquan (Chautauqua, N.Y.), Century Illustrated Magazine, New York Evening Post, and Montreal Daily Witness. Many of her stories of the Chinese and Eurasian communities were collected in Mrs. Spring Fragrance, published in Chicago in 1912. Although she always hoped to be able to give up stenography and earn her living with her writing, she was never sufficiently established to do so. Her sister Winnifred Babcock, who was born in Montreal, would take on the guise of a Japanese Eurasian and would become a prolific and successful writer.

Eaton’s own sensitivity to her mixed blood seems to have been responsible at least in part for her unsettled life. She wrote in 1909, “So I roam backward and forward across the continent. When I am East, my heart is West. When I am West, my heart is East. Before long I hope to be in China. As my life began in my father’s country it may end in my mother’s.” Despite plans to do so, Eaton never did visit China, prevented at one time by wars. When she died in 1914, the Chinese community of Montreal erected a monument to her “In grateful memory” on her burial site at Mount Royal Cemetery. Eaton may be considered the first North American of Chinese extraction to write realistically and convincingly of Chinese culture and the difficulties and prejudices encountered by the Chinese in North America.

Often using the pseudonym Sui Sin Far, Edith Maud Eaton wrote numerous articles and stories which appeared mainly in American newspapers and magazines; notable among them are the following: “Spring impressions” in the Dominion Illustrated (Montreal), 6 (1890): 358–59; “Leaves from the mental portfolio of an Eurasian,” “Literary notes,” and “Chinese workman in America” in the Independent (Boston), 21 Jan. 1909, 15 Aug. 1912, and 3 July 1913, respectively; and “The story of Iso” and “A love story of the Orient” in the Lotus (Kansas City, Mo.), August 1896: 117–19 and October 1896: 203–7. A collection of her stories was published under the title Mrs. Spring Fragrance (Chicago, 1912). Her correspondence with the associate editor of the Century Illustrated Magazine (New York and London) is preserved among the Century Company records in the New York Public Library,

Globe, 9 April 1914. New York Times, 7 July 1912: 405; 9 April 1914. K.-K. Cheung and Stan Yogi, Asian American literature: an annotated bibliography (New York, 1988). Directory, Montreal, 1865–1916. Amy Ling, “Edith Eaton: pioneer Chinamerican writer and feminist,” American Literary Realism, 1870–1910 (Arlington, Tex.), 16 (1983): 287–98; “Winnifred Eaton: ethnic chameleon and popular success,” MELUS (Los Angeles), 11 (1984), no.3: 5–15. Lorraine McMullen, “Double colonization: femininity and ethnicity in the writings of Edith Eaton,” in Crisis and creativity in the new literatures in English: Canada, ed. Geoffrey Davis (Amsterdam and Atlanta, Ga, 1990), 141–51. S. E. Solberg, “Sui Sin Far/Edith Eaton: the first Chinese-American fictionist,” MELUS, 8 (1981), no.1: 27–39. Annette White-Parks, Sui Sin Far/Edith Maude Eaton: a literary biography (Urbana, Ill., 1995).

Cite This Article

Lorraine McMullen, “EATON, EDITH MAUD (Sui Sin Far),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 25, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eaton_edith_maud_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/eaton_edith_maud_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | Lorraine McMullen |

| Title of Article: | EATON, EDITH MAUD (Sui Sin Far) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | April 25, 2025 |