Source: Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

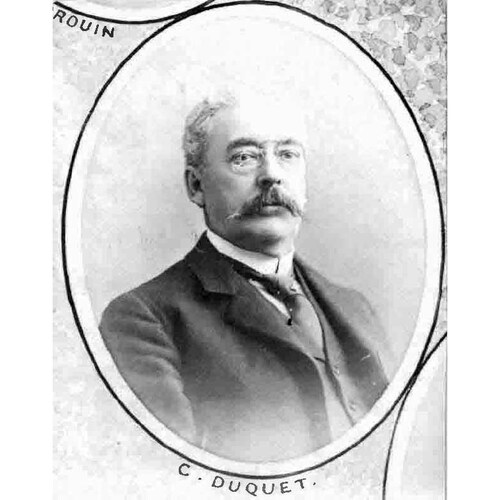

DUQUET, CYRILLE, clockmaker, jeweller, inventor, and politician; b. 31 March 1841 at Quebec, son of Joseph Duquet, a labourer, and Madeleine Therrien (Terrien); m. there 22 Feb. 1865 Adélaïde Saint-Laurent, daughter of Jean-Baptiste Saint-Laurent and Adélaïde Gazzo (Gazeau), and they had 16 children; d. there 1 Dec. 1922.

After studying with the Brothers of the Christian Schools, Cyrille Duquet was apprenticed at the age of 13 to goldsmith Joseph-Prudent Gendron, whose shop was on Rue Saint-Jean in Quebec City. When Gendron decided to move in 1862, Duquet’s apprenticeship was coming to an end. He promptly approached the owner of the building with a proposal to go into business for himself at the same address. An agreement was reached, and for a time Duquet shared his premises with Simon Levy, who sold watches and jewellery.

Duquet was undoubtedly reliable and hard-working. He also had a passion for science. Not content just to assemble and install clocks or to make and sell jewellery, he attempted to attract attention by displaying his inventions and creations in his store window. Duquet liked to dazzle, astonish, and fascinate, but he also had a practical mind. With Professor François-Alexandre-Hubert La Rue*, he designed a magnetic sand separator in 1868–69. Around 1870 Duquet invented a device that made it possible to monitor the exact time at which watchmen checking the fire alarm telegraph system reached various points in their rounds. The patent was purchased that year by the New Haven Clock Company in the United States. He also conceived the idea of installing electric clocks in steeples and in the towers of high buildings.

It was Duquet’s telephone receiver, however, that brought him fame. He reportedly corresponded with Alexander Graham Bell on the progress of their respective experiments, although none of their letters has thus far been located. What is indeed certain is that Duquet obtained a patent on 1 Feb. 1878 for a number of modifications “giving more facility for the transmission of sound and adding to its acoustic properties,” and in particular for the design of a new apparatus combining the speaker and receiver in a single unit. After a few experiments in linking his store on Rue de la Fabrique (where Rue Saint-Jean begins) and a second store – which he and Louis Dalaire owned – in Saint-Roch ward, and in linking Ottawa and Montreal, he began to set up a few regular telephone lines, including one with Spencer Wood, the residence of the lieutenant governor, and another with the Couvent Jésus-Marie in Sillery, where one of his daughters was studying.

Convinced that Duquet was using Bell’s invention, Charles Fleetford Sise*, vice-president of the Canadian Telephone Company, ordered him in a letter dated 31 Dec. 1880 to “desist from the manufacture of such telephones.” Stung to the quick, Duquet replied on 7 Jan. 1881 that “the patent you are making such a fuss about has expired and is null and void.” “Kindly cease your threats of a lawsuit, which do not frighten me in the least,” he added, and he concluded, “If you want an unchallengeable patent, I advise you to buy mine . . . as soon as possible, because the longer you wait, the more it will cost you.” On 11 May 1882 the Quebec Superior Court ruled in favour of the Canadian Telephone Company (which was merged that year into the Bell Telephone Company of Canada). From the $5,000 claimed on 1 April 1881, the company had reduced its “demand for damages to the sum of ten dollars,” “being convinced that the Defendant acted in good faith,” as judge William Collis Meredith explained.

The real reason the plaintiffs had reduced their claim to such an extent was not Duquet’s good faith, but rather the company’s interest in his various improvements. On 15 May 1882 Duquet sold his “instruments, patents, patent rights, licence agreements, contracts, plant, apparatus, chattels and good will” for $2,100 and abandoned all projects related to telephones. His fame, however, opened a new world to him: politics. François Langelier*, a prominent Liberal lawyer, had just come onto the municipal scene. As city councillor for Saint-Louis ward, Duquet would be associated with him from 1884 to 1890.

This was a period when the face of the city was changing. Sidewalks were being laid down or repaired, streets were being widened or paved, and the water system was being altered and extended by contractor Horace Jansen Beemer*. Between 1886 and 1889 street lighting was converted from gas to electricity. Duquet loved this kind of challenge. But it was in the realm of electricity that he devoted himself wholeheartedly. He took sweet revenge on Sigismund Mohr*, who had testified against him in 1882. As manager of the Quebec and Levis Electric Light Company, Mohr set up a network of electric lighting whose costs were under constant review by Duquet.

In 1890 Duquet concentrated on his own business affairs. He sold his house at 153 Grande Allée to John Breakey*, intending to take up residence above the new store being built for him on Rue Saint-Jean, at the foot of Rue de la Fabrique, on the site of his first shop.

Perhaps Duquet had undertaken too much or the economic situation may have been too bleak. In any case, he was on the verge of bankruptcy in July 1896. He had creditors in New York, Boston, Toronto, Hamilton, and, of course, Montreal and Quebec. At the head of the line was Moïse Schwob, with his claim for $9,854.81 of the $19,381.93 owed to non-preferential creditors. To this sum must be added the amount due a preferential creditor, the Quebec Permanent Building Society, for a total debt of $31,825.93. On 5 July Duquet turned over his property, which was valued at $42,448.20, including $19,447.78 for his business and $18,500 for his buildings. At a special meeting of creditors on 28 Sept. 1896, “a resolution was moved by M. Schwob, seconded by Augustin Gaboury, and carried unanimously, that, since Mr Cyrille Duquet had got from his creditors an agreement to accept twenty-five cents on the dollar,” he should be authorized to resume “full possession and enjoyment of his property.”

In July 1904 Duquet attempted to make a comeback on the municipal scene. He won election as alderman for Palais ward by a narrow majority of ten votes, defeating dentist Henri-Edmond Casgrain*, his neighbour on Rue Saint-Jean and more particularly his rival as a well-known inventor. This time he took his seat along with Simon-Napoléon Parent*, who was both mayor of the city and Liberal premier of the province. The newspaper L’Événement, now Conservative again [see Louis-Joseph Demers*], listed him as one of Parent’s opponents. In its 17 Feb. 1906 issue, it ranked him among the “reform candidates” in the forthcoming election. This time he won a resounding victory, with a majority of 138. Georges Garneau* was also elected to the city council, and he was immediately approached to be the next mayor, replacing Parent, who had left this office in January.

At council meetings Duquet was quite spirited. He was always attracting comment because of his speeches, which were mostly out of order. By joining forces with some 20 mlas who were bringing suit against L’Événement, he eventually turned it against him and he was defeated in the election of February 1908 by Lawrence Arthur Cannon*.

At the age of 67 Duquet could now afford to take stock, to recall the difficulties he had encountered, and the controversies – in particular one in March 1871, when an artisan named P.-E. Poulin had publicly accused him of wrongfully taking credit for creating a chain and cross for the archbishop of Quebec. There was also his venture in the spring of 1887 into the production of natural gas in Louiseville, which had left him, when he went bankrupt, with 400 worthless shares in the Compagnie de Gaz Combustible. But on the other hand, he could walk proudly about his city, remembering how it had changed, admiring the residence built for him on the Grande Allée, the other house where his business was located, and all the clocks on the most beautiful buildings of Quebec, including the city hall, the legislative building, the customs house, and St Matthew’s Church. And his name was on the faces of clocks that had movements made in the United States.

From now on Duquet could devote his time to music, his business, and his family. Sixteen children had been born from 1866 to 1887, and eight of them were still alive. His eldest, Eva, had made him a grandfather several times over, much to his delight. His daughter Alice entered the noviciate of the Sœurs Missionnaires de Notre-Dame d’Afrique. His son Georges-Henri chose an artistic career, while Arthur assisted him in his business.

Tireless, curious, tenacious, and at times a dreamer, Duquet was a self-made man of a high order. Among his boundless interests, scientific and technical advances fascinated and stimulated him, and they held few secrets for him. Duquet had achieved the feat of reconciling the arts and business, science and politics. Fiercely independent, he became a legendary figure through his creations and inventions.

[Jeanne Hardy, the wife of Arthur Duquet, who managed his father’s business until 1933, prepared a short biography of Cyrille Duquet which, as she stated, was drawn from family tradition and from contemporary newspaper articles, including pieces by Damase Potvin*, Lorenzo Saint-Mars, and Mgr Victor Tremblay. This unpublished biography of around 10 pages, and several other documents concerning Cyrille Duquet, is held by Denise Duquet (Lamonde) of Sainte-Foy, Qué. A number of useful documents are found in the Bell Canada Information Resource Centre (Montreal), Bell Canada Hist. Coll., 21732, and several articles on Duquet and on the telephone are available in the general collection of the Soc. Hist. du Saguenay (Chicoutimi, Qué.). A steam-engine Duquet invented in 1865 is at the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière, Qué.); the mace of the Assemblée Nationale du Québec is among the best knows of his works as a silversmith. One building bears his name, 1500 Charest Boulevard Ouest in Quebec City, the headquarters of the communications branch of the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications du Québec. Duquet’s building on Rue Saint-Jean, which consisted of three storeys, was demolished to make way for a bank, and his residence on the Grande Allée has been replaced by the Loews Le Concorde Hotel. In 1983 the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique named a new chair of computer and information science in his honour. d.v.]

ANQ-Q, CE301-S1, 31 mars 1841; CE301-S97, 22 févr. 1865; Index BMS, dist. judiciaire de Québec, Notre-Dame de Québec, 2 déc. 1922; P1000, D2396; TP11, S1, SS2, SSS1, dossiers 170 (1891), 730 (1896), 1251 (1885), 1338 (1889), 1411 (1889), 1536 (1873), 1544 (1881), 1955 (1891), 2462 (1890). AVQ, QD4-1A, 1662–63; QD4-1G, 1739-02–05; QP1-4, 40/0004, 62/0005. Monique Duval, “Québec doit le téléphone . . . à Cyrille Duquet,” Le Soleil, 11 mai 1977. L’Événement, 13, 17, 20 févr. 1906; 5 nov. 1907; 10, 18 févr. 1908. Le Journal de Québec, 29 nov. 1866; 26 févr. 1868; 27, 31 mars 1871. Le Soleil, 16 févr. 1904. “Orfèvrerie: établissement de M. Cyrille Duquet,” in Annuaire du commerce et de l’industrie de Québec . . . (Québec), 1873: 44–46. René Lagacé, “Cyrille Duquet, inventeur de renom,” Concorde (Québec), 7 (1956), nos.6–7: 9–11. Alyne Le Bel, “Le magicien de la rue Saint-Jean: l’inventeur Cyrille Duquet,” Cap-aux-Diamants (Québec), 4 (1988–89), no.4: 45–48. William Patten, Pioneering the telephone in Canada (Montreal, 1926).

Cite This Article

Denis Vaugeois, “DUQUET, CYRILLE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duquet_cyrille_15E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/duquet_cyrille_15E.html |

| Author of Article: | Denis Vaugeois |

| Title of Article: | DUQUET, CYRILLE |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 15 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2005 |

| Year of revision: | 2005 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |