Source: Link

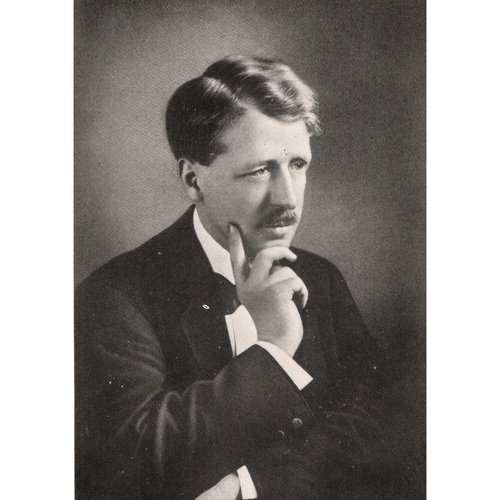

DÉCARY, ERNEST-RÉMI (baptized Joseph-Rémi-Ernest), notary, politician, office holder, and businessman; b. 9 Dec. 1877 in Montreal, son of Alphonse-Clovis Décary, a notary, and Rose de Lima Serre, dite St-Jean; m. first 16 April 1901 Éva Lallemand in Montreal, and they had three sons; they were legally separated in 1923 and divorced the following year in New York State; m. secondly 13 Feb. 1934 Marjorie Law Norris, the widow of James Macdonald Eakins, in New York City; d. 23 Feb. 1940 in Dorval, Que., and was buried three days later in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemetery, Montreal.

A descendant of Jean Descaris, a pioneer who settled in Ville-Marie (Montreal) around the middle of the 17th century, Ernest-Rémi Décary studied at the Collège Sainte-Marie in Montreal. He then enrolled in the faculty of law at the Université Laval, in the same city, where he received his llb in June 1900. On 14 September he was licensed to practise as a notary and, about 1902, he took over from his father as the partner of the notary Joseph-Alphonse Brunet.

Some six years later, Décary began working on his own until, probably in 1912, he created the firm of Décary, Barlow and Joron with notaries Joseph Crossman Barlow and Lionel Joron. The firm specialized in banking and railways. The Dominion Bank, the Trader’s Bank of Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, and the Canadian Northern Railway were among its clients. The latter company had plans to build a railway tunnel of three and a quarter miles under Mount Royal (the work began in July 1912) and a station in downtown Montreal. In a single day, the CNR purchased 4,800 acres of agricultural land on the north slope of Mount Royal for the ridiculously low price of $120,000. Décary saw to the acquisition of the property, which led to the creation of the Town of Mount Royal, incorporated on 21 Dec. 1912. From 1913 to 1918 he sat on the council of the new municipality.

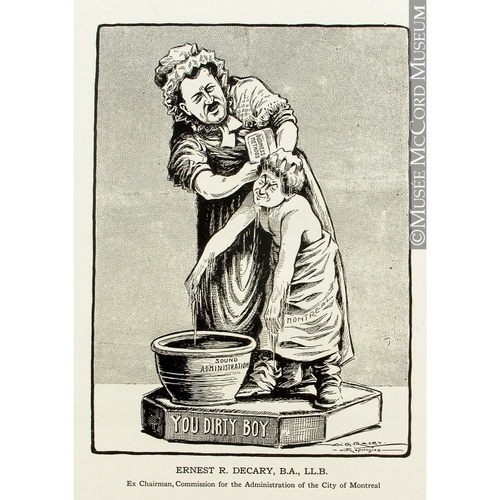

In 1918 the deficits accumulated during the previous two years were creating severe financial difficulty for the City of Montreal. The debts of the 20-odd municipalities annexed since the 1880s were partly responsible for this situation. Despite the strong opposition of the mayor, Médéric Martin*, Montreal was placed under trusteeship by the provincial government for an initial period of four years. Enacted on 9 Feb. 1918, the Law to amend the charter of the City of Montreal created an administrative commission, which replaced the board of commissioners [see Lawrence John Cannon*]. The mandate of the Administrative Commission of the City of Montreal was to put the city’s finances in order and to assume overall management of municipal affairs, thereby curtailing the powers of the mayor and municipal council. On 5 April the government of Sir Lomer Gouin* appointed the five commission members for a four-year term: Décary, Liberal mps Alphonse Verville* and Charles Marcil, engineer Robert Alexander Ross, and city treasurer Charles Arnoldi. The latter would soon retire and be replaced by businessman Gaspard De Serres. Décary – a Liberal Party supporter and brother-in-law of Jérémie-Louis Décarie, the provincial secretary and Gouin’s political lieutenant in Montreal – was named chairman, with an annual salary of $12,000. The five commissioners were sworn in on 9 April and held their first meeting the following day. Over the next few days, to make up for an anticipated shortfall of nearly four million dollars, they increased the property tax, the business turnover tax, the water tax, and the price of permits. They reorganized municipal services by grouping them together and laid off more than 150 people.

A major strike by workers responsible for water supply and incineration as well as police officers and firemen broke out on 12 Dec. 1918. The dispute was brief but tumultuous: after a 33-hour strike marked by confrontations and riots, the employees agreed to arbitration. They achieved small wage increases, but the city refused to recognize the international bodies to which the police and firefighters’ unions wanted to affiliate (the Policemen’s Federal Labor Union No.62 and the International Association of Fire Fighters Local Union 125). The white-collar workers, in turn, demanded a salary increase. The commission offered them bonuses instead. It also adopted a regulation governing consistent attendance by office holders, introduced job classification, and set up the municipal service commission (1919–25), whose mandate was to ensure that the hiring and appointment of city employees were fair and free of favouritism. On 1 Jan. 1920 the waterworks employees launched a strike that sporadically left local residents without water. The administrative commission succeeded in restoring service and fired the strikers. Faced with this impasse, Gouin formed a committee of inquiry to determine who was responsible for the dispute, which ended on 4 February with the return of the dismissed employees.

The administrative commission, which was already unpopular with municipal wage earners, fell out of favour with the general population. The provincial government shortened its term by one year and on 14 Feb. 1920 created the Montreal Charter Commission. Chaired by Sir Hormisdas Laporte, this commission was given the task of proposing a new system of administration for the city. The Law concerning the charter of the City of Montreal, enacted on 19 March 1921, put forward two forms of government. In a referendum, the municipal voters of Montreal had to choose between “plan A” and “plan B.” Plan A suggested a city council limited to 15 members elected by the population as a whole for a four-year term, a mayor appointed by the council, and a manager who would be in charge of the city’s administration. Under plan B there would be one councillor in each of the city’s 35 wards elected for a two-year term, a mayor elected by the citizens, and an executive committee with wide powers. On 16 May Montrealers approved the second choice with 62 per cent support. Municipal elections were held on 18 October and mayor Martin was re-elected. The Administrative Commission of the City of Montreal held its last meeting on 31 Oct. 1921; in accordance with the provisions of the charter, it ended its activities when the new council met for the first time, and so Décary left the municipal scene. The autonomy of the City of Montreal, its mayor, and its council were thus restored. Despite its unpopularity, the commission had succeeded in reining in the debt, stabilizing municipal finances, and, according to historian Michèle Dagenais, “putting in place a suitable framework for the formation of a modern bureaucracy.”

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Décary worked for the Title Guarantee and Trust Corporation of Canada, a trust and loan company, as general manager, vice-president, and then, from 8 April 1929, president and chief executive officer. On the same day he also became chairman of the administrative commission of the Université de Montréal, which awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1931. At that time he was also chairman of the Montreal Finance Corporation Limited and, since 1922, had been a member of the board of directors of the Canadian National Railway Company.

The 1930s, however, were marked by financial setbacks for Décary. In October 1934 Éva Lallemand, whom he had married in 1901, claimed in the Superior Court of Quebec that his alimony payments for the two previous years were in arrears. Décary was to pay her an annual sum of $6,000, which was equal to one-third of his salary. The court dossier and the newspapers revealed that the couple had stopped living together in 1917, that they were legally separated on 13 Nov. 1923, and that Décary had obtained a divorce in the Supreme Court of New York on 19 Dec. 1924. The following year, his ex-wife married Edwin T. Murdoch, a New York City lawyer. Some months before the case was heard, Décary married Marjorie Law Norris, from Kansas. On 27 Nov. 1935 judge Cecil Gordon Mackinnon ruled in favour of Décary, who was not yet, however, out of difficulty. On 26 Dec. 1938 judge Louis Boyer of the Superior Court of Quebec appointed a liquidator for the Title Guarantee and Trust Corporation of Canada. Décary remained a member of the Provincial Board of Notaries until 1 Jan. 1939. He was declared bankrupt on 15 March, and on the 30th the provincial government enacted the Law authorizing an inquiry into the affairs of the Title Guarantee and Trust Corporation of Canada. This commission of inquiry would never see the light of day.

At the time of Ernest-Rémi Décary’s death and funeral in 1940, which was attended by many leading personalities, such as the former premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau*, the Montreal dailies dwelt mainly on Décary’s rise to the city’s top position. On 16 Nov. 1992 the town of Mount Royal honoured the memory of the man who had been one of its first councillors and had contributed several parcels of land for use as parks by renaming Dunrae Park after him.

BANQ-CAM, CE601-S29, 9 déc. 1877; CE601-S51, 12 janv. 1869; TP11, S2, SS2, SSS1; SSS6; SS10, SSS4. FD, Notre-Dame (Montréal), 26 févr. 1940; Saint-Henri (Montréal), 16 avril 1901. Univ. de Montréal, Div. des arch., A 33, 88/10; A 59, 47/1; 55/2; A 60, 8/4/29. VM-SA, VM6, B.855; D.001.2-7; VM18. Le Canada (Montréal), 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28 janv. 1920; 9 avril 1929; 24 févr. 1940. Le Devoir, 27 déc. 1938; 1, 2 mars 1939; 26 févr. 1940. Gazette (Montreal), 24 Feb. 1940. Monetary Times (Toronto), 13 Oct. 1922. Montreal Daily Star, 2 Oct. 1934, 24 Feb. 1940. New York Times, 14 Feb. 1934. La Patrie, 6, 9, 10 avril, 12, 13, 14 déc. 1918; 2 janv., 2 févr. 1920; 25, 26 févr. 1940. La Presse, 2 oct. 1934, 1er mars 1939, 24 févr. 1940. BCF, 1920. Canadian who’s who, 1936/37. Michèle Dagenais, Des pouvoirs et des hommes: l’administration municipale de Montréal, 1900–1950 (Montréal et Kingston, Ontario, 2000); “Dynamiques d’une bureaucratie: l’administration municipale de Montréal et ses fonctionnaires, 1900–1945” (thèse de phd, univ. du Québec à Montréal, 1992). William Gaudry, “La commission administrative et la modernisation des structures politiques et administratives de Montréal, 1918–1921” (mémoire de ma, univ. de Montréal, 2014). Linteau, Hist. de Montréal, 405–22. É.‑Z. Massicotte, Les familles Descary, Descarries, Décary et Décarie, 1650–1909: histoire, généalogie, portraits (Montréal, 1910). Montreal, pictorial and biographical: deluxe supplement (Winnipeg, 1914). Prominent men of Canada, 1931–32, ed. Ross Hamilton (Montreal, [1932?]). Que., Statutes, 1918, c.84; 1920, c.127; 1921, c.112; 1922, c.128; 1939, c.137. Rumilly, Hist. de Montréal, vol.4: 7–10, 20–41. Town of Mount Royal Clerk’s Office and Mario Nadon, Town of Mount Royal, toponymic heritage: streets and public parks ([Mont-Royal, Que., 1995]).

Cite This Article

Mario Robert, “DÉCARY, ERNEST-RÉMI (baptized Joseph-Rémi-Ernest),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 22, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/decary_ernest_remi_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/decary_ernest_remi_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Mario Robert |

| Title of Article: | DÉCARY, ERNEST-RÉMI (baptized Joseph-Rémi-Ernest) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2019 |

| Year of revision: | 2019 |

| Access Date: | November 22, 2024 |