Source: Link

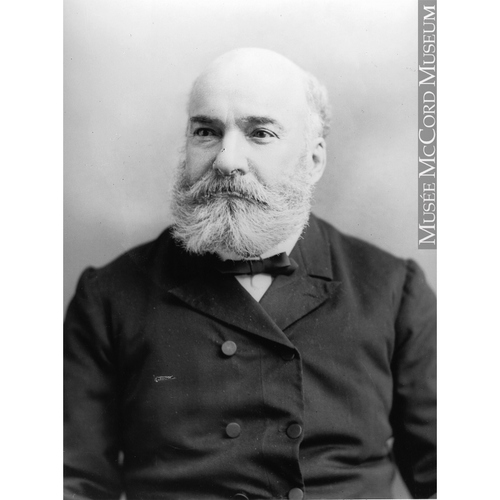

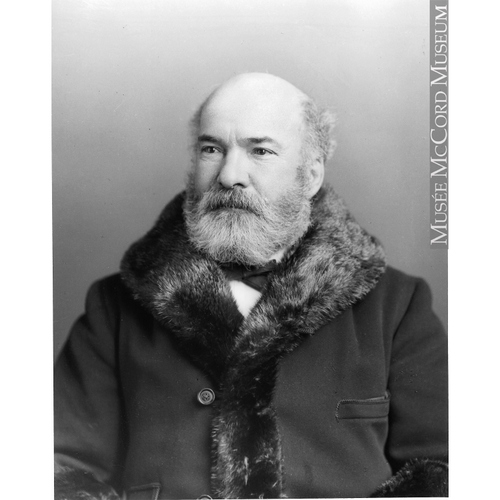

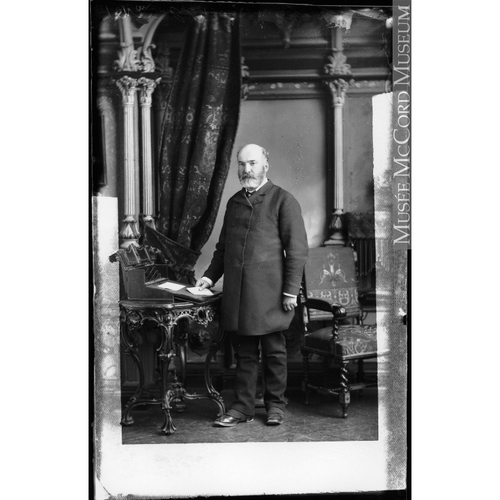

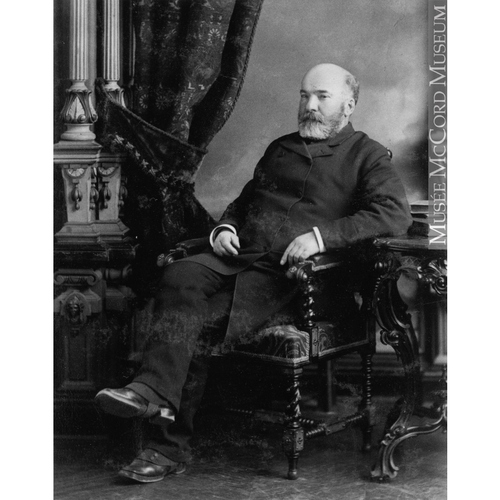

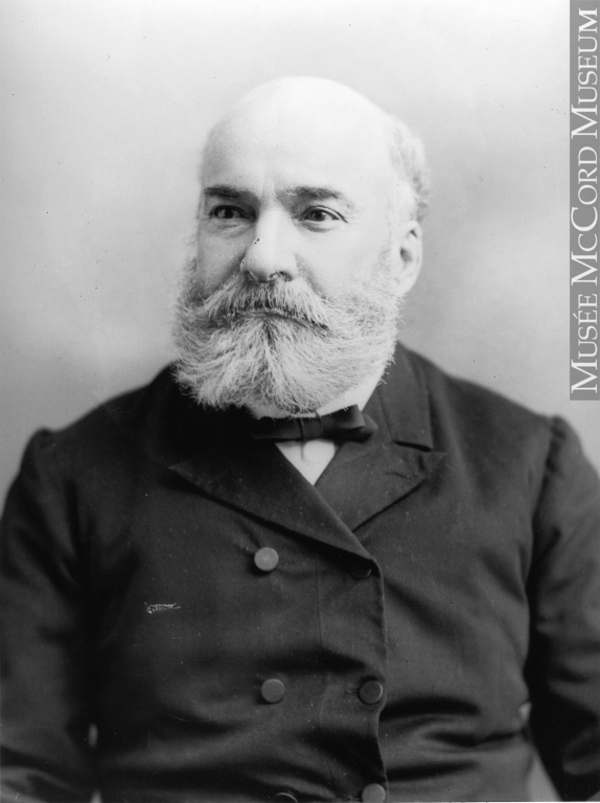

CLENDINNENG (Clendinning), WILLIAM, manufacturer, merchant, philanthropist, and politician; b. 22 June 1833 in Cavan (Republic of Ireland); m. 3 May 1853 Rachel Newmarsh, an Englishwoman, in Montreal, and they had five sons and four daughters; d. 21 June 1907 in Depew, N.Y.

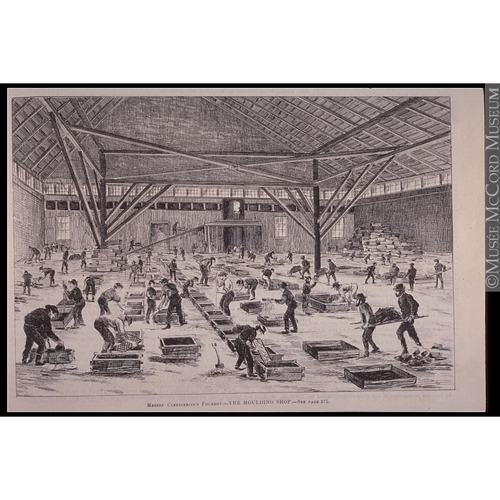

William Clendinneng arrived in Montreal with his family in 1847, at the age of 14. His origins were humble, and he began his rise in society in 1852, when he went to work as a clerk at William Rodden’s foundry in Sainte-Anne ward. The business specialized in manufacturing various models of stoves, but made bedsteads, scales, and ploughs as well; it also forged and cast iron products of all kinds. Clendinneng came to the attention of Rodden, who took him on as a partner in November 1858. In the spring of 1861 an observer noted that the company was being run mainly by Clendinneng, while Rodden devoted most of his time to his career in municipal politics.

Under Clendinneng’s leadership, William Rodden and Company grew quickly. The foundry carried on business as before, but in addition it opened a store on Rue Saint-Jacques in the summer of 1862 to reap the profits from marketing its own products. Although the firm had been in a precarious financial position in the 1840s, it was now on a solid footing and became one of Canada’s largest foundries. In 1861 it had 65 employees on average. There were 90 by 1864, 150 in 1871, 180 in 1872, and 300 in 1886.

In January 1868 Clendinneng bought out Rodden’s share, valued at $50,000, which he had to pay for in annual instalments. He thus became sole owner of the company. At that point he was estimated to be worth $30,000. Under his ownership, the foundry continued to prosper, and in May 1874 his wealth was thought to amount to $100,000. The following month he helped found Mead Manufacturing Company, incorporated to make sewing-machines and various cast-iron products. However, because of the effects in Canada of the world-wide economic depression, it never commenced operations. In January 1884 Clendinneng brought in his son William as a partner in the foundry, which from then on was known as William Clendinneng and Son.

Like many businessmen of his time, Clendinneng was involved in a number of charitable associations, but he was much more active in this sphere than most of the bourgeoisie of the period. From 1857 he participated in the work of the Irish Protestant Benevolent Society of Montreal and the Young Men’s Christian Association, and he became a director of both. During the 1860s he also served every year on the executive of one or two other Protestant charitable bodies: the English Workingmen’s Benefit Society of Montreal, the United Protestant Workingmen’s Benefit Society, and the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge. Probably around 1870 Clendinneng decided to follow in Rodden’s footsteps and began making plans to enter politics eventually. He devoted more energy to good works, and from 1870 to 1880 he served as a director, on average, of five organizations every year. In addition to the societies mentioned above, he was associated with the French Canadian Missionary Society, the Montreal Religious Tract Society, the Montreal Auxiliary Bible Society, the Montreal Dispensary, the Montreal General Hospital, the Montreal Sailors Institute, the Mechanics’ Institute of Montreal, the Board of Trade of Montreal, and the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Clendinneng accumulated considerable political capital through his commitment to social causes, and in 1876 he was elected city councillor for Saint-Antoine ward. He represented the area from 1876 to 1879 and from 1888 to 1893. He also served as acting mayor in the fall of 1888.

From 1880 Clendinneng was involved mainly with the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. He sat on their boards of directors from 1869 to 1894 and from 1875 to 1894 respectively. His reputation was solidly established. La Presse of Montreal portrayed him as “an affable man, a man of the people, a committed citizen, an active industrialist whom everyone holds in high regard because he is good, charitable, and kindly to the workers, to whom he is a sincere friend.” In June 1890 Clendinneng’s record of social and political dedication was crowned by his election as the provincial Conservative member for Montreal, Division No.4, following a hard-fought campaign. He did not run in 1892.

Clendinneng, again like many businessmen, not only tried to help the poor in Montreal but also developed a paternalistic relationship with his own workers. In 1872 a reading-room was opened for them at the foundry, stocked with local newspapers, magazines, and technical publications. During the 1870s the company established a tradition of holding annual summer picnics. The employees took a train or steamboat to a spot outside the city to relax. Clendinneng also showed his desire for good relations with them on Saint-Jean-Baptiste day in 1881, when, with the union insignia pinned to his chest, he marched proudly with the officials of the Montreal local of the Iron Molders International Union along the main streets of the city, parading with their members. However, Clendinneng could be inflexible with his employees. In the summer of 1872 he had joined a coalition of 50 principal Montreal businessmen to oppose workers’ demands for a reduction of the workday from ten hours to nine. Furthermore, in 1886 he undermined the influence of the iron molders’ union in a strike that his company had provoked by hiring someone who was not a union member.

Clendinneng’s business career suffered some setbacks towards the end of his life. These reverses probably explain why he withdrew from his philanthropic and political activities. According to the Montreal Daily Star, the closure of the Banque du Peuple in July 1895 dealt him a severe blow. It was probably a factor in the November 1895 bankruptcy of the Canada Pipe and Foundry Company, of which Clendinneng and his son William had been partners since its creation in June 1889. The William Clendinneng and Son foundry also seems to have suffered severely. From 23 April 1896 to 19 June 1902 a William Mann of Montreal was in charge of all operations under the company name. During this period Clendinneng was apparently forced to find work with iron merchants in Montreal because of his financial difficulties. As soon as Mann stopped conducting business under the foundry’s name on 20 June 1902, the company’s activities were placed under the sole name of Rachel Newmarsh, wife of William Clendinneng, “separated in property” from him since 1898. At her death four months later, Clendinneng resumed the operation of the company on his own account, with the assistance of his sons William and George. But when Mann launched a lawsuit in February 1904, the foundry declared bankruptcy. Clendinneng left Montreal the same year. On 21 June 1907, in Depew, N.Y., where he had been living with one of his daughters for just five months, he was hit by a train as he was returning from a walk and died almost instantly. His place of burial is not known, but records show he was not interred in Mount Royal Cemetery in Outremont, where his wife is buried.

AC, Montréal, État civil, Méthodistes, Mountain Methodist (Montreal), October 1902. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, 5: 30; 6: 86, 92. BE, Montréal, bureau des raisons sociales, William Clendinneng et al. NA, RG 31, C1, 1861, Montreal. Canadian Illustrated News (Montreal), 4 May 1872. Gazette (Montreal), 22 June 1907. Montreal Daily Herald, 22 June 1907: 13. Montreal Daily Star, 22 Aug. 1876, 30 June 1886, 2 March 1889, 22 June 1907. La Patrie, 24 juin 1907. La Presse, 1e juill. 1886; 14–19 juin 1890; 10 févr. 1894; 24 juin 1907. Peter Bischoff, “La formation des traditions de solidarité ouvrière chez les mouleurs montréalais: la longue marche vers le syndicalisme (1859–1881),” Labour, 21 (1988): 25–26, 31–32, 35–37. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer, 504. Canada Gazette, 1874/75: 143; 1893: 1886. CPG, 1891. Directory, Montreal, 1847–1907. K. G. C. Huttemeyer, Les intérêts commerciaux de Montréal et Québec et leurs manufactures (Montréal, 1889), 158–59. Industries of Canada, city of Montreal, historical and descriptive review, leading firms and moneyed institutions (Montreal, 1886), 125. Lamothe, Hist. de Montréal, 741. Montreal, Board of Trade, A souvenir of the opening of the new building, one thousand, eight hundred and ninety-three (Montreal, 1893), 161. Montreal business sketches . . . (Montreal, 1864), 97–100. Quebec Official Gazette, 1889: 1313; 1895: 2615; 1904: 478, 1664.

Cite This Article

Peter Bischoff and Robert Tremblay, “CLENDINNENG (Clendinning), WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 6, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clendinneng_william_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clendinneng_william_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Peter Bischoff and Robert Tremblay |

| Title of Article: | CLENDINNENG (Clendinning), WILLIAM |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | March 6, 2026 |