![Address intended to be delivered in the City Hall, Hamilton, February 7, 1851, on the subject of slavery (Hamilton, [Ont.], 1851).

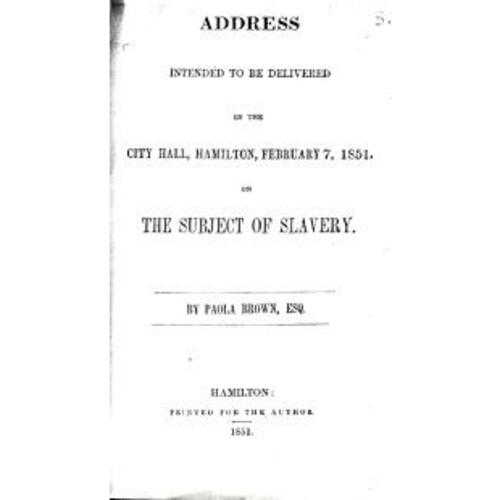

From: The Souls of Black Folk: Hamilton's Stewart Memorial Community Original title: Address intended to be delivered in the City Hall, Hamilton, February 7, 1851, on the subject of slavery (Hamilton, [Ont.], 1851).

From: The Souls of Black Folk: Hamilton's Stewart Memorial Community](/bioimages/w600.13829.jpg)

Source: Link

BROWN, PAOLA (Paoli, Paole, Peole), town-crier and handyman; fl. 1828–52.

Tradition has ascribed to Paola Brown, who was born in Pennsylvania around 1807, the status of a runaway slave from a southern plantation. However, his first name, possibly derived either from a town near Philadelphia or from the famous liberator of Corsica (Pasquale Paoli, who died in 1807), combined with the fact that he claimed to be literate, suggests that he was probably an indentured urban servant or freeman rather than a rural slave.

Brown surfaced in Upper Canada in late 1828 as a peripatetic leader of scattered black families between Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake) and Dundas. He prepared two petitions to secure land for a settlement that would draw together black families from Niagara to Waterloo. The first petition claimed that the black settlement designated by the government for Oro Township was too distant and appealed for a more conveniently located grant. The Executive Council rejected this petition early in December, insisting that the blacks settle in or near Oro Township. The second petition followed shortly and asked for approval to form a company to purchase a block of clergy reserve land on the Grand River where the petitioners planned to cultivate tobacco. On 17 Jan. 1829 the council rejected this petition, stating that the desired block of land had not yet been surveyed and was not for sale at that time. One reason why the petitioners pleaded for special consideration was a perceived need for self-protection: cases of blacks being kidnapped and returned to the United States were cited in the petitions. Moreover, racially inspired petty violence had occurred in Upper Canada and, not long after his petitioning, Brown himself was a victim. In May 1829 George Gurnett*, the publisher of the Gore Gazette of Ancaster, was accused of “violent assault and battery upon one Paoli Brown, a man of colour.”

Unable to establish a new settlement but retaining his passionate interest in black welfare in the Niagara and Gore districts, Brown gravitated to Hamilton. The flourishing state of Hamilton in the late 1820s and during the 1830s attracted a small black community, in which Brown assumed a leadership role. After 1833 he marshalled the area’s blacks during annual celebrations on 1 August commemorating the abolition of slavery in the British empire. He also continued to be involved in petitions on behalf of blacks. In 1837 he signed one from the black community appealing for a fair extradition hearing in the case of runaway slave Jesse Happy. Five years later his name heads a list of 170 “coloured persons of Hamilton and its vicinity” who petitioned Sir Allan Napier MacNab* to protest the forcible return of Nelson Hackett* from Sandwich (Windsor) to slavery in the United States.

During his years in Hamilton, Brown supported himself and his wife by working as a handyman and by acting as town-crier and crier for an auctioneer. Local accounts describe him as unusual and popular; Laura B. Durand noted, in a later anecdotal and condescending remembrance, that “his vanity and affectation were as typical of his race as his good nature and volubility.” As crier, dressed in white trousers and a white top hat in warm weather and a large military cape in winter, he exercised his “deep and sonorous” voice aided by a large handbell. Some citizens, however, were less than pleased by these activities, and insults and demands for silence reached Brown. By 1849 enough of them considered him a nuisance that a by-law was passed which, if strictly enforced, would have prevented him from shouting his messages and ringing his bell.

Brown’s interest in education and religion was a source of cruel amusement and inspired the “sporting youths” of Hamilton to make him the butt of jokes. Although he claimed that the “great authors of antiquity” were his “constant companions,” Durand alleged that he was “absolutely uneducated.” His carrying a book in hand would prompt sarcastic questions about how he was getting on with his studies. In turn, the community’s behaviour reinforced a fatalism in Brown that must have made his pronouncements about the evils of the day a bitter outpouring rather than a humorous display from an amiable local character.

In 1843 a major Adventist movement, led by William Miller, swept over western New York proclaiming that the world was beyond secular rescue and that the second coming was at hand. Many of the leaders of this movement, which was strongest in Rochester, were prominent abolitionists, and they described a world in which violence and corruption were growing stronger. Brown, an adherent and proselytizer, was a member of the tabernacle in Hamilton and was one of those who assembled on 22 Oct. 1844 in the hope of being taken to heaven; that the appointed time passed without incident must have only exacerbated the cruelty already evident in Hamilton.

Early in 1851 more than 200 citizens invited Brown to lecture on the evils of slavery. On 7 February a large crowd assembled but he was barely into his address when a practical joker extinguished the lights and precipitated a panic. Brown’s speech, published that year, fused in prophetic rhetoric his passion for black freedom in the United States and his vision of divine justice. The message was clear: “Slaveholders, I call God, I call Angels, I call Men, to witness, that your destruction is at hand, and will be speedily consummated, unless you repent.”

The 1852 census notes that Brown lived in the basement offices of Hugh Bowlby Willson*, a prominent Hamilton lawyer and land speculator. Paola Brown disappears thereafter and it has been alleged that he died a pauper.

Paola Brown is the author of Address intended to be delivered in the City Hall, Hamilton, February 7, 1851, on the subject of slavery (Hamilton, [Ont.], 1851). A report of the speech and its disruption appeared as “Lecture of Paola Brown, Esq., on slavery,” Weekly Spectator, 13 Feb. 1851.

HPL, Hamilton census and assessment rolls, 1837, 1840–41; Scrapbooks, H. F. Gardiner, 215: 43; 216: 51; 273: 109. McMaster Univ. Library (Hamilton), Research Coll. and Arch., Hamilton Police Village minutes (typescript). PAC, RG 1, E3, 35: 225–27; L3, 50: B15/115; RG 5, A1: 50676–78. Canadian Freeman (York [Toronto]), 5 Jan. 1832. Hamilton Spectator, and Journal of Commerce, 25 July 1849. DHB. G. E. French, Men of colour: an historical account of the black settlement on Wilberforce Street and in Oro Township, Simcoe County, Ontario, 1819–1949 (Stroud, Ont., 1978). D. G. Hill, The freedom-seekers: blacks in early Canada (Agincourt [Toronto], 1981). L. B. Durand, “‘Peole’ Brown: town crier; an incident of 1843,” Canadian Magazine, 50 (November 1917–April 1918): 291–94. C. R. McCullough, “Head of the Lake: a review of an old-time address” and “Colourful characters of bygone years,” Hamilton Spectator, 1 Nov. 1941: 15, and 14 Sept. 1946: 5.

Cite This Article

John C. Weaver, “BROWN, PAOLA (Paoli, Paole, Peole),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 1, 2026, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_paola_8E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brown_paola_8E.html |

| Author of Article: | John C. Weaver |

| Title of Article: | BROWN, PAOLA (Paoli, Paole, Peole) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 8 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1985 |

| Year of revision: | 1985 |

| Access Date: | January 1, 2026 |