Source: Link

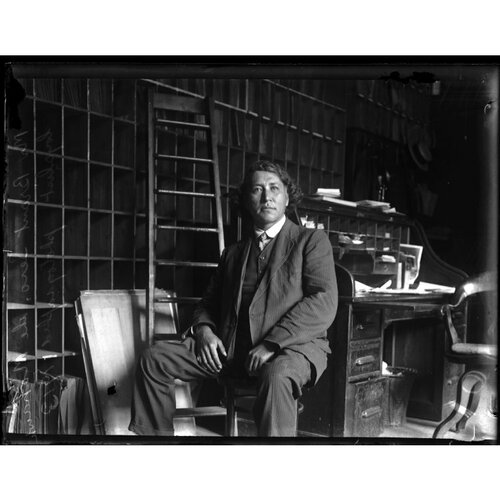

BRANT-SERO, JOHN OJIJATEKHA (baptized John Sero, rebaptized John Brant-Sero; his Mohawk name, Ojijatekha, which he used as part of his given name, means “burning flower”), Mohawk celebrity, actor, interpreter, and lecturer; b. 10 June 1867 on the Six Nations Reserve near Brantford, Upper Canada, first child of Dennis Sero (Shero), a farmer, and Ellen Funn; m. 29 June 1896 Frances Baynes Kirby, née Pinder, of Fishwick (Preston), England; d. 7 May 1914 in London, England.

John Ojijatekha Brant-Sero’s descent on his mother’s side from Isaac, first son of Joseph Brant [Thayendanegea*], and on his father’s from the Bay of Quinte Mohawks joined the two traditions of Mohawk loyalist heritage. Few details are known about his early life other than that he attended the reserve school and the Mohawk Institute to study carpentry. As he grew older he realized the value of education and wanted to learn, as he put it, “the business ways of the whites.” Accordingly, he petitioned the Six Nations Council, which granted him money to help defray the costs of a business course.

Brant-Sero left business college, he claimed, “with a fair knowledge of shorthand and some dexterity with the typewriter.” He then went to Toronto, where in 1888 and 1889 he found employment, it seems, as a machine-hand with Charles Boeckh and Son, manufacturers of brushes, brooms, and woodenware. While in Toronto he became fascinated with the theatre. By his own account he spent a number of years there on the stage, appearing in “one of Joe Murphy’s plays.” In August 1889 he spoke on the government of the Six Nations at the Toronto meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In 1891 he left for England, where, again by his own admission, he spent some time on the stage; he claimed to have appeared in the American spectacle On the frontier, which played in Liverpool in the spring of 1891. While in England, at the age of 29, he married the 48-year-old widow of a clergyman. Since it was impossible at the time to produce his Methodist baptismal certificate, he was rechristened in an Anglican service, taking Brant as part of his name. On the marriage certificate his occupation was listed as divinity student.

Brant-Sero returned to Canada with his bride and settled in Hamilton, Ont., where they took a large house on the outskirts of the city and “cut a wide swath in society.” John evidently had a “deep interest in public, sporting and social affairs.” The Toronto Globe of 16 Oct. 1897 devoted a feature article to a huge party the couple gave to celebrate Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee; they invited several hundred Indians to camp on their grounds and roasted an ox whole.

Following his return, Brant-Sero had attracted the attention of Ontario’s literati through his knowledge of the Mohawk language and the myths, songs, and traditions of his people. He was engaged as an informant and interpreter by David Boyle, curator of the archaeology department of the Ontario Provincial Museum in Toronto, who, in his report of 1898, admired Brant-Sero as “one of the brightest and most intelligent Iroquois ever born on the Reserve.” Witty, outgoing, and ambitious, Brant-Sero was elected second vice-president in 1899 of the Wentworth Historical Society and also of the Ontario Historical Society, where, in the opinion of fellow vice-president David Breakenridge Read*, he was “the moving spirit in the Six Nations Historical matters.” His tenure, however, was short-lived.

In the spring of 1900 he went to Chicago and made a successful lecture tour of the United States, enlivening and enriching “his lectures with Indian songs, giving them in the original and then explaining the meaning of the Indian words and the peculiarities of the Indian music.” In one lecture he recited from Shakespeare’s Othello in both English and Mohawk. Evidently, when he went to Chicago he abandoned his wife. Later in 1900 he travelled to the Cape Colony to enlist in one of the contingents fighting in the South African War. He was refused because he was not of European origin. He succeeded, however, in getting on the civilian staff at a remount depot, but eventually he resigned and went to England.

With his dashing good looks, flair for the dramatic, and fluency in English he quickly won the notice of’ London’s men of science. In 1900 he read a paper before the British Association for the Advancement of Science. He became so highly regarded that articles about him appeared that year in the column “People talked about” in Leslie’s Weekly, a popular American illustrated. The next year he was elected a fellow of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, but he resigned in 1902. His lecture tours in England attracted enthusiastic crowds. On 13 Feb. 1902, for example, he spoke to an audience of 1,311 in Liverpool on “Canada and the Indians” and used musical and lantern illustrations.

Less than a month later Brant-Sero appeared in Liverpool’s police court for neglecting to pay for the support of his child. Describing himself as an anthropologist engaged in the “study of mankind . . . principally . . . the study of the backward races, and the American Indians in particular,” he claimed recognition by major associations. He none the less pleaded that “in a conservative country like England it was almost impossible to make money.” Although he was enterprising enough and promoted himself well, he must have had difficulty financing the stylish life he enjoyed. Whether he went to prison or was eventually able to pay his fine cannot be verified. He did tell the court that he “had recently married a lady in London who possessed a small income.”

Only sporadic incidents are known of Brant-Sero’s life between 1902 and his death. His views on Canada’s Indians and the Mohawks especially, recorded in the Journal of American Folk-lore in 1905, were optimistic, intensely patriotic, and tinged perhaps with some delusion when he stated that in Canada his people were “on a footing of perfect equality.” On 19 May 1906, from Bridlington, England, he wrote to the Globe advocating a memorial to honour the 100th anniversary of the death of his famous ancestor, Joseph Brant. A year later, in a lecture in London, he took the occasion of the centenary to discuss the education of Indians in Ontario. On 26 Aug. 1908 he visited Folkestone, England, where, “in full native dress, with feathery headgear” and “jet-black hair, which fell over the nape of his neck,” he won third prize at an international beauty show for gentlemen. In 1911 his brief article on a medicinal herb his people called o-nõ-dah appeared in the Journal of American Folklore over the date-line of Hamilton, Ont.

Brant-Sero died in 1914 of “acute pneumococcal meningitis” at West London Hospital in England. His occupation on his death certificate was given as journalist. In its obituary the Hamilton Spectator described him as “the best known Mohawk Indian of the present century.”

Much that has been written about Brant-Sero, by himself and others, cannot be verified: his attendance at the University of Cambridge; his stage appearances; his lecture to the Royal Saxon Geographical Society in Dresden, Germany, in 1900; and his full-length portrait in costume at the British Museum. Brant-Sero appears to have distinguished between the sort of genuine historical information that he gave Boyle and the historical societies, and what he gave out at public lectures in Britain and the United States. His mention of “backward races” on one occasion, “perfect equality” on another, and the theatricality of his lectures suggest a shrewd appreciation of what white audiences wanted to hear and see. He may have created a personal mythology in his restless travels, but his extant letters and articles reveal an articulate, likeable, and romantic character whose passionate attachment to the British crown and his Mohawk heritage gained him many admirers during his lifetime.

John Ojijatekha Brant-Sero is the author of “Some descendants of Joseph Brant” in Ontario Hist. Soc., Papers and Records (later OH), 1 (1899): 113–17; “The Six-Nations Indians in the province of Ontario, Canada,” in Wentworth Hist. Soc., Journal and Trans. (Hamilton, Ont.), 2 (1899): 62–73; “Indian Rights Association after government scalp” in Wilshire’s Magazine (Los Angeles), October 1903: 70–75 (copy in AO, Pamphlet Coll., 1903, no.60); and “Views of a Mohawk Indian” and “O-nõ-dah” in Journal of American Folk-lore (Boston and New York; etc.), 18 (1905): 160–62 and 24 (1911): 251, respectively. “Dekanawideh: the lawgiver of the Caniengahakas,” a lecture he delivered before the British Assoc. for the Advancement of Science, was published in Man (London), 1 (1901): 166–70.

Brant-Sero’s letter of 1906 to the Globe advocating a Joseph Brant memorial is reproduced in Shocked and appalled: a century of letters to the “Globe and Mail”, ed. Jack Kapica (Toronto, 1985), 51–52, and his lecture in London of the following year appears in the Globe, 13 Aug. 1907: 6. According to Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912), Brant-Sero, poet and dramatist, also translated “God save the King” into Mohawk and produced a poem entitled “The beaver and the fox,” but no record of either of these items has been located.

AO, F 1076-A-19, box 5, envelope 1. HPL, Scrapbooks, H. F. Gardiner, 113: 55. NA, MG 26, G: 66090–91. Chicago Evening Post, 19 March 1900. Evening Express (Liverpool, Eng.), 31 March 1901. Folkestone Express, Sandgate, Shorncliffe and Hythe Advertiser (Folkestone, Eng.), 29 Aug. 1908. Fort Beaufort Advocate and Adelaide Opinion (Fort Beaufort, Cape Colony), 7 Sept. 1900. Globe, 16 Oct. 1897. Hamilton Spectator, 3 March 1902, 26 May 1914. Ottawa Citizen, 17 Jan. 1901. American Assoc. for the Advancement of Science, Proc. (Salem, Mass.), 1889: 371. Directory, Toronto, 1888–89. C. T. Foreman, Indians abroad, 1493–1938 (Norman, Okla, 1943), 99–100. Gerald Killan, Preserving Ontario’s heritage: a history of the Ontario Historical Society (Ottawa, 1976). Leslie’s Weekly, Illustrated (New York), 19 March, 28 July 1900. Liverpool, Public libraries, museums, and art gallery committee, Annual report, 1902. Ontario Provincial Museum, Annual archœological report (Toronto), 1898: 3.

Cite This Article

S. Penny Petrone, “BRANT-SERO, JOHN OJIJATEKHA (baptized John Sero, rebaptized John Brant-Sero) (Ojijatekha),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 12, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brant_sero_john_ojijatekha_14E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/brant_sero_john_ojijatekha_14E.html |

| Author of Article: | S. Penny Petrone |

| Title of Article: | BRANT-SERO, JOHN OJIJATEKHA (baptized John Sero, rebaptized John Brant-Sero) (Ojijatekha) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1998 |

| Year of revision: | 1998 |

| Access Date: | December 12, 2025 |