Source: Link

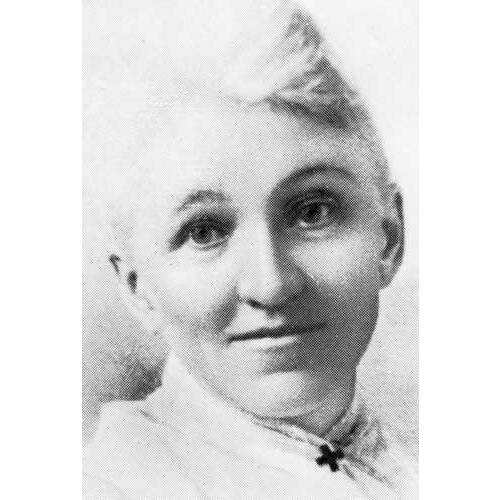

BOUCHER, MARGARET RUTTAN (Scott), stenographer, administrator of home-nursing services, and social reformer; b. 28 July 1855 or 1856 in Colborne, Northumberland County, Upper Canada, daughter of Robert Mant Boucher, a lawyer, and Mary Ruttan; granddaughter of Henry Ruttan*; m. 23 Oct. 1878 William Hepburne Scott (d. 1881) in Campbellford, Ont.; they had no children; d. 1 Aug. 1931 in Winnipeg and was buried there in St John’s cemetery.

As a child, Margaret Boucher lived in Colborne and Peterborough. After the death of her father in 1868, she went to stay with aunts in Campbellford. There she met a young girl from the Müller Homes, a large orphanage in Bristol, England, whose founder never asked for funds because he believed that God would provide what was required. This encounter renewed an interest, instilled earlier by her mother, in helping the poor through faith and prayer.

At age 22 or 23 Boucher married lawyer and mla William Hepburne Scott. Widowed less than three years later, she was left without financial means. She found office work in Peterborough with the Midland Railway of Canada. Later, she was transferred to the audit office of the Grand Trunk Railway in Montreal, where she was responsible for supervising 50 young women. Not physically strong, she overtaxed herself and her health broke down. On her doctor’s advice, she moved to “the bracing climate” of Winnipeg in 1886. She initially found employment at the Dominion Lands Office and later worked as a stenographer for Hough and Campbell, a local law firm. Scott, who would become known for her skill, had learned shorthand from businessman Frederick William Heubach after the only individual providing formal instruction refused to teach her because she was a woman.

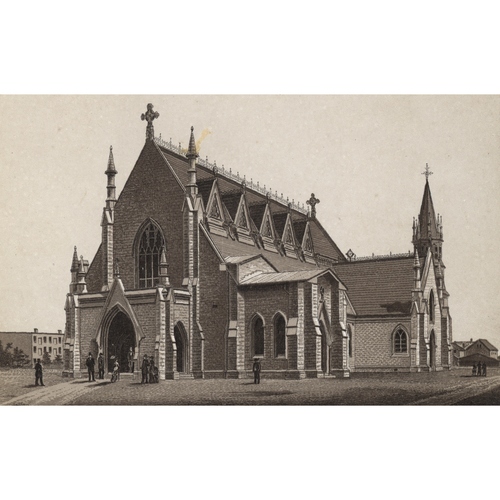

A devout Anglican, Scott volunteered for the Reverend Cecil Caldbeck Owen at Holy Trinity Church, where she sorted correspondence related to charity matters. Owen encouraged her to give up her office position and to devote herself to the care of the poor. “Mr. Owen,” she said, “prayed me out of office work.” In 1897 she resigned from Hough and Campbell and moved into a small room in the Winnipeg Lodging and Coffee House, which was owned by Holy Trinity, and devoted the rest of her life to charitable concerns and social reform. In addition to organizing Sunday-school classes and religious services for the men who boarded at the house, she established a weekly mothers’ meeting group, offering spiritual guidance as well as material assistance. She also sought out the needy at the police court and often spent her nights nursing female prisoners.

During the early 20th century, Winnipeg experienced tremendous population growth as thousands of immigrants poured into the city from eastern Europe and Britain. Their initial years in Winnipeg were marked by long periods of badly paid and irregular employment. Many could not afford medical care. Once Scott saw the plight of those who were sick and poor, she focused her attention on helping them. She spent long days visiting in their homes and delivering donated food and clothing. To make her task easier, two of her supporters provided a pony and cart; Scott and the pony, Jo, became a familiar sight in Winnipeg’s immigrant districts. Faithful to her belief that God would provide what was needed, she never accepted a salary.

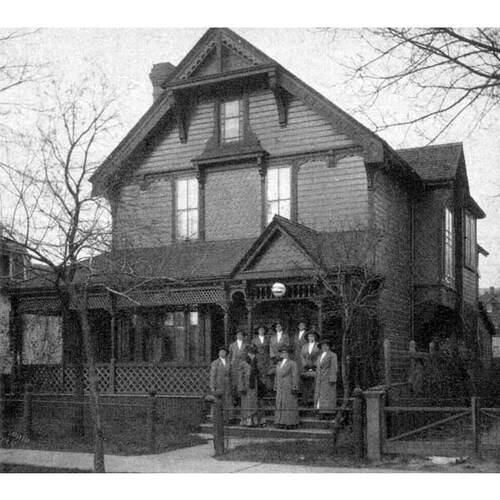

Scott had no formal medical training, but read at night to learn about the operation of nursing missions, public-health departments, charities, and social-services agencies in other cities. In 1900 Ernest H. Taylor, a local businessman, donated half the money necessary to employ a trained nurse to assist Scott and persuaded civic authorities to supply the rest. After his death in 1903, the city continued to fund this position. In 1904, armed with financing from churches, citizens, and the municipal government, a group of prominent women interested in Scott’s work founded the Margaret Scott Nursing Mission. Among them were Minnie Julia Beatrice Campbell [Buck*], Elizabeth Jane Moody [Holland*], and the wives of many notable businessmen, politicians, and clergymen. The following year its permanent headquarters were established at 99 George St, close to impoverished neighbourhoods. Scott moved into the mission’s building in 1907. From its inception, the mission had never publicly solicited funds. At various times during its history, it would be supported by federal, provincial, and municipal grants and by the Winnipeg Foundation [see William Forbes Alloway*]. Scott brought the needs of working-class and immigrant populations to the attention of government officials. She played a leading role in the creation of the Associated Charities in Winnipeg in 1908 and convinced the city council to create winter work projects for unemployed men.

In addition to carrying out her own work, Scott oversaw, with the assistance of an all-female board, the development of one of the most comprehensive home-nursing programs in western Canada. The mission, which employed eight nurses in 1915, became a model for other western home-nursing associations and provided valuable field experience for student nurses in Winnipeg.

In 1910, in cooperation with the city’s Department of Public Health, Scott had established a child hygiene service in the mission, which provided health education and material support for mothers of newborns. After it demonstrated its efficacy in reducing Winnipeg’s appalling infant-mortality rates, the program was taken over by the department in 1914. Three years earlier Scott had set up the Little Nurses’ League, which taught schoolchildren, particularly young girls, about food preparation, hygiene, and childcare. The Winnipeg School Board assumed responsibility for the league in 1913 and expanded it to 13 other schools. In recognition of her pioneering work in establishing programs to reduce infant mortality in Winnipeg, the Margaret Scott School, which opened in September 1920, was named in her honour.

Known as the “Angel of Poverty Row,” “Winnipeg’s Angel of Mercy,” and “the Florence Nightingale of Winnipeg,” Margaret Ruttan Scott died in the Winnipeg General Hospital in 1931 after almost 45 years of community service. Flags in the city flew at half mast, and her funeral service at Holy Trinity Church, conducted by Archbishop Samuel Pritchard Matheson*, was attended by the mayor, Ralph Humphreys Webb, council members, and many who had been touched by her life. Scott was honoured posthumously in 1932 by the Cosmopolitan Club of Winnipeg “for outstanding service to the city.” A ward was named in her memory at the Winnipeg General Hospital in 1943, and the Margaret Scott Nursing Mission Scholarship was established two years later to assist “a nurse or nurses registered in the province of Manitoba wishing to take post graduate work” in public health. The home-nursing program she had founded was discontinued in 1942 during a major reorganization of public-health services in Winnipeg. Responsibility for the patients still on its caseload was transferred to the Winnipeg branch of the Victorian Order of Nurses for Canada.

AM, MG 10, B9. City of Winnipeg, Arch. and records control branch, Dept. of Health, annual reports, 1911, 1913–14. Man., Dept. of Healthy Living, Seniors and Consumer Affairs, Consumer and Corporate Affairs, Vital statistics agency (Winnipeg), no.1931-036097. Evening Telegram (Winnipeg), 26 May 1904. Manitoba Free Press, 27 May 1904, 12 June 1905, 3 Aug. 1931. Mary Moore, “The mission that never asked a dime: the increditable story of an incredible woman,” Winnipeg Free Press, 14 March 1964: 21–22. Edith Paterson, “It happened here: Margaret Scott devotes life to Winnipeg’s needy,” Winnipeg Free Press, 18 Jan. 1975, New Leisure [suppl.]: 5. Winnipeg Evening Tribune, 5 Aug. 1931. Winnipeg Tribune, 3 Aug. 1931. American Public Health Assoc., Public health activities in Winnipeg, 1941: report of study (n.p., 1941). A. F. J. Artibise, Winnipeg: a social history of urban growth, 1874–1914 (Montreal and London, 1975). Diane DeGraves, “Margaret Scott, 1856–1931: health and social service innovator,” in Extraordinary ordinary women: Manitoba women & their stories, ed. Colleen Armstrong (Winnipeg, 2000), 65–66. “The Florence Nightingale of Winnipeg: story of Mrs. Margaret Scott and her labor of great love,” Canadian Nurse (Toronto), 11 (1915): 136–44. Helena Macvicar, Margaret Scott: a tribute; the Margaret Scott Nursing Mission ([Winnipeg, 1947?]).

Cite This Article

Carolyn Crippen and Marion McKay, “BOUCHER, MARGARET RUTTAN (Scott),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 21, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/boucher_margaret_ruttan_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/boucher_margaret_ruttan_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Carolyn Crippen and Marion McKay |

| Title of Article: | BOUCHER, MARGARET RUTTAN (Scott) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 2013 |

| Year of revision: | 2016 |

| Access Date: | December 21, 2024 |