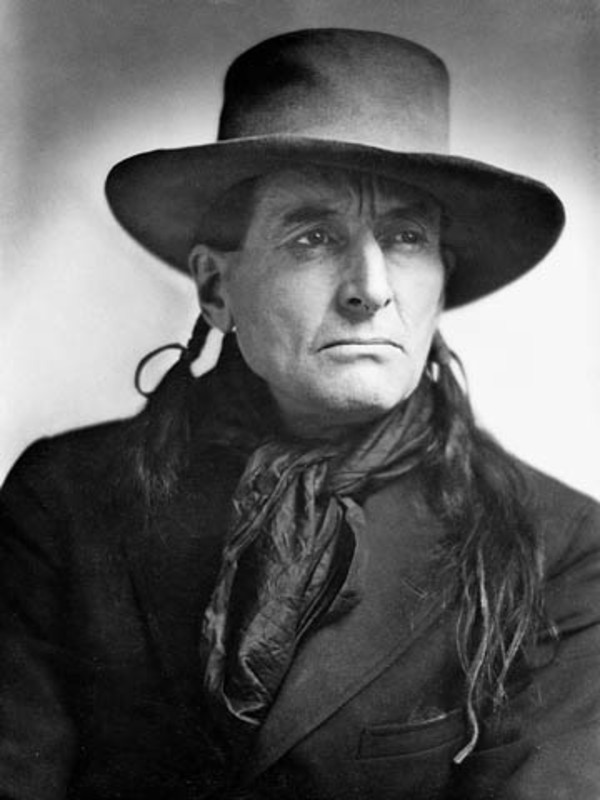

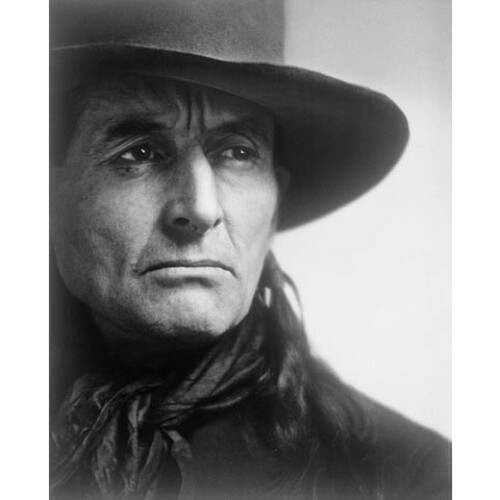

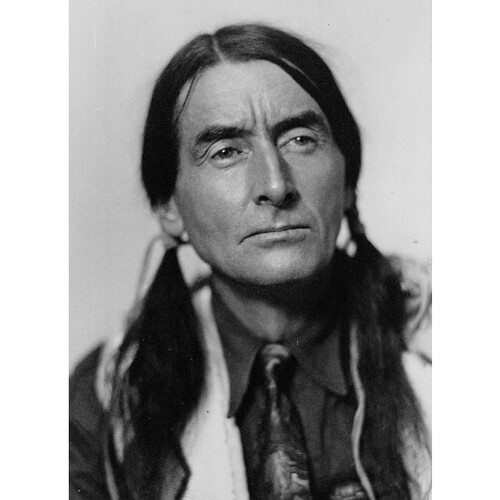

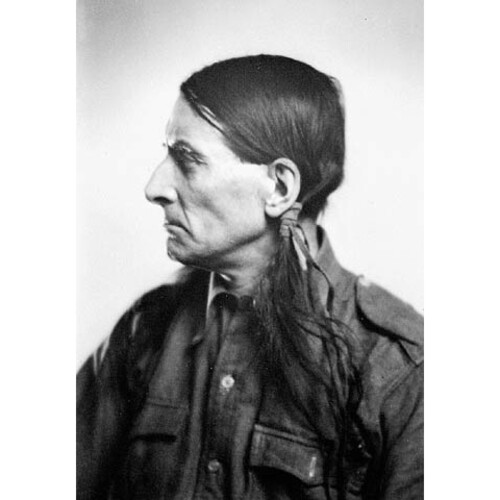

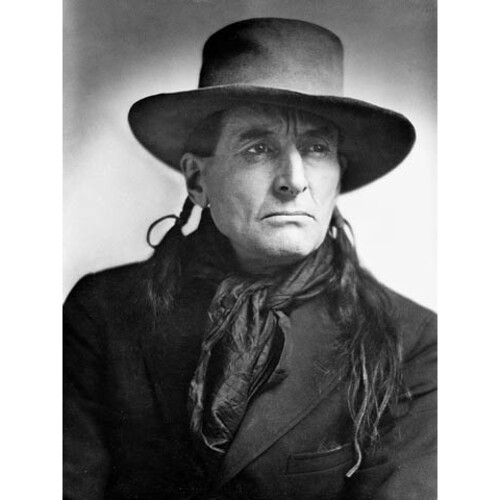

BELANEY, Archibald Stansfeld, known as Grey Owl and Wa-sha-quon-asin, forest ranger, guide, trapper, environmentalist, conservation officer, writer, and lecturer; b. 18 Sept. 1888 in Hastings, England, elder son of George Furmage Belaney and Kathleen Verena (Kittie) Cox; m. first 23 Aug. 1910 Angele Egwuna on Bear Island in Lake Temagami, Ont., and they had at least two children; m. secondly 10 Feb. 1917 Florence Ivy Mary Holmes in Hollington, near Hastings; they divorced on 9 Aug. 1922; m. thirdly early June 1926 Gertrude Philomen Bernard, known as Anahareo, in an aboriginal ceremony at Lac Simon, Que., and they had a daughter; the couple separated in 1936; m. fourthly 5 Dec. 1936 Yvonne Perrier in Montreal; he also had a son with Marie Girard (Gerrard, Jero); d. 13 April 1938 in Prince Albert, Sask.

Archie Belaney was raised by two aunts, Janet Adelaide (Ada) and Julia Caroline (Carrie) Belaney, in the town of Hastings on the English Channel. His paternal grandfather and namesake, Archibald, was a Scottish-born merchant and shipbroker, and Archibald’s wife, Juliana Mary Henrietta (Julia) Jackson, was a descendant on her mother’s side of the Stansfelds, a prominent family from Halifax in Yorkshire. After her husband’s early death, Julia Belaney lavished all her attention and revenues on their only son, George, who received an expensive education. With his mother’s help he began a business in London in tea and coffee that soon foundered, and then left on a costly big-game expedition to South Africa. Upon his return he departed for the United States to invest in an orange-grove plantation.

When this Florida investment failed, George went back to Britain with his wife, English-born Kittie, pregnant and half his age. Kittie gave birth to Archie shortly after their arrival in Hastings, where Julia and her two unmarried daughters had recently moved from London. By this time George’s alcoholism had sharply reduced the family’s fortune. He still refused to settle down, and two years later he abandoned Kittie, who had just borne their second son. George would eventually travel to North America, where he apparently died about 1910; the exact time and circumstances remain unknown. Shortly before their ne’er-do-well brother decamped, Ada and Carrie had intervened and taken Archie to live with them.

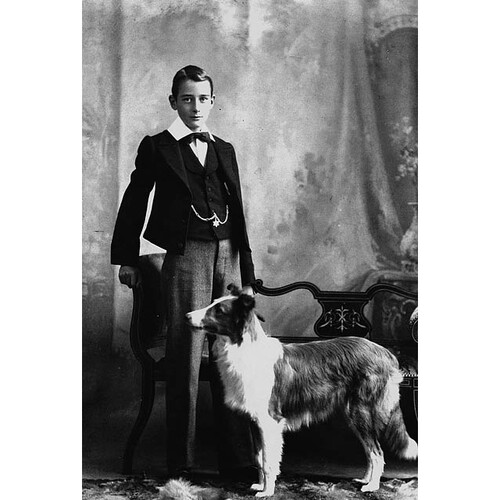

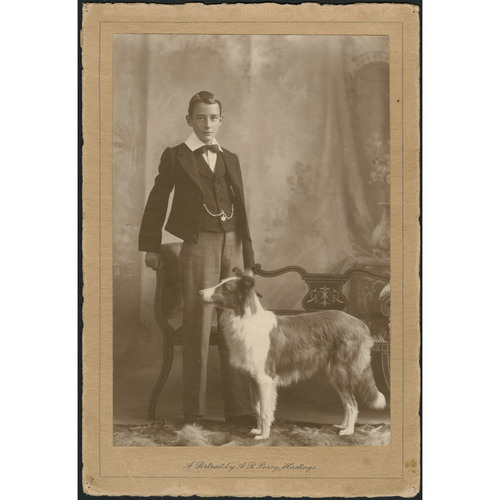

The granitelike Ada ran the Belaney household. She taught Archie first at home, instilling in him a lifelong love of literature and music. The stern, formal woman stressed obedience and excellence, just as she did with the collies she bred. After three years in a small church school, Archie entered the Hastings Grammar School at the age of 11 in 1899. As a young boy, his passions were North American Indians and wildlife. Ada, to her credit, understood the importance of the natural world to him and allowed him to keep his rabbits, snakes, and mice on the top floor of their home.

With his books on Indians, his menagerie, and his solitary walks to look for plants and animals, the lonely boy lived in a dream world of his own making. Creatively, he invented two fictional parents. To explain their absence he developed the story further, later stating that his father was a western plainsman and his mother a Native American. So began the fabulous story of his origins that he would elaborate and refine for the remainder of his life.

Archie did well in English and religious knowledge, but in other respects his academic record was mediocre. Ada allowed him to leave school at age 15, and he took up a clerk’s job at a local lumberyard for two years. Through his continued reading, and his nature walks in the open spaces around Hastings, his admiration for the North American Indians grew, so much so that he wanted to go and live with them in the Canadian forest. When he was 17, his aunt was persuaded to let him do so.

Archie sailed to Halifax in March 1906 and from there moved on to Toronto, where he worked briefly to save money for his northern journey. He took the train first to Témiskaming, Que., near the Ottawa River, and then a few months later went further west to Lake Temagami, the home of a small Ojibwa community, the Teme-Augama Anishnabai (the deep-water people). John Egwuna and his family welcomed the curious young Englishman. John’s niece Angele Egwuna taught Archie their language and gave him lessons in canoeing and trapping. In 1910 he married Angele in a Christian ceremony, but only a year later, lacking any model of a normal family, he behaved exactly as his father had, and abandoned her and their infant daughter, Agnes.

In the spring of 1912 Archie Belaney appeared in the tiny lumbering town of Biscotasing – known as Bisco – some 100 miles west of Temagami, on the Canadian Pacific Railway between Sudbury and Chapleau. In the village he became well known for his skill in knife throwing, his expert piano playing at dances, and his heavy drinking. To support himself he worked in the summer as a forest ranger and guide, and trapped in the winter. By this point he had lost his English accent and, if asked, he would repeat his well-polished tale of being the son of a Scots frontiersman and an Apache woman. Having left his legal wife, he entered into a relationship with Marie Girard, a Métis woman in Bisco. When they separated early in the winter of 1914–15, he apparently did not know that she was pregnant. She died of tuberculosis shortly after giving birth to their son, John, in the fall of 1915.

Canada had entered World War I in early August 1914 and Archie had enlisted, but not immediately, and not in northeastern Ontario; instead he signed up the following May, in Digby, N.S. His first military order was to get his hair cut. It then hung down to his shoulders. When asked upon his enlistment if he had had any previous military experience, he said he had, in the “Mexican Scouts, 28th Dragoons.” At the front Archie, an excellent shot, served as a sniper until a serious injury in his right foot took him out of the war in April 1916. He was hospitalized in England.

By chance, he spent some time at a military hospital in Hastings. He got in touch with his two aunts. They in turn contacted Ivy Holmes, the daughter of a good friend of theirs and a boyhood acquaintance of Archie’s. Ivy, an attractive, outgoing woman, had become a professional dancer. She and her troupe had performed throughout Europe before the war. With his aunts and Ivy, Archie reverted to his English accent, did not drink, and, of course, made no reference to his marriage in Temagami. Ivy enjoyed Archie’s company; he was a wonderful storyteller. They fell in love and, with his aunts’ blessing, married in February 1917. Ivy accepted Archie’s plan of a life together in the Canadian forest. The couple decided that he should leave first (while the war was still on, wives could not accompany their husbands back to Canada). He sailed on 19 Sept. 1917. She never saw him again.

Archie returned to Bisco totally overwhelmed by the horrors of the war. He had seen inconceivable slaughter. His injury was a constant reminder of the conflict and its senselessness. On account of the damage to the central area of his foot, he never regained the complete use of it. Moreover, his personal life was in total disarray. He made no call to Ivy to join him in Canada, and finally told her about his previous marriage. She obtained a divorce in 1922 on the grounds of bigamy. Although he had visited Angele shortly after his return to Canada in 1917, he soon decided not to remain with her. In Bisco he learned about his son, John Girard, who came home from the Chapleau Indian Residential School in the summer. The boy did not know who his father was, however. Mrs Edith Langevin, the native woman who was John’s guardian, did not tell him until after Archie had moved away. As a staunch teetotaller, she was revolted by Archie’s drinking habits.

The friendship of the Espaniels, a local Ojibwa family, saved Archie. As long as he did not drink and he behaved himself, they allowed him to stay with them on their trapping grounds for several winters in the early 1920s. With them he perfected his command of their language and learned more about the Ojibwa way of life. He gained a new appreciation of the northern forest. In 1925 Archie left Bisco and returned to Lake Temagami, to Angele. She had last seen him two years earlier, when she was quite ill. This time, as before, he did not stay long. She would give birth to their second daughter, Flora, in 1926.

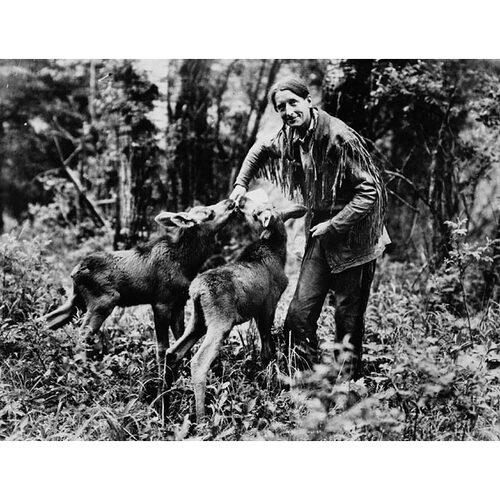

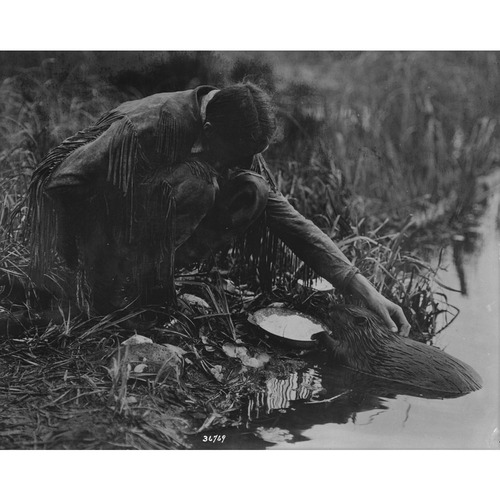

A chance meeting in the late summer of 1925 with Gertrude Bernard, a young Iroquois woman, led Archie to propose that they spend a winter trapping together in the Abitibi region of Quebec. The turning point of his life came in the months to follow. He truly loved Gertrude, to whom he gave the name Anahareo. She had been raised in the town of Mattawa, Ont., east of North Bay, not in the bush. Ironically, the English-born Archie taught the aboriginal woman how to survive in the forest. That winter, however, he had great difficulty in locating enough fur-bearing animals to make a living. In particular, he found a tremendous decline in the number of beaver, the result of an influx of trappers from other areas, Ontario having banned non-natives from running traplines.

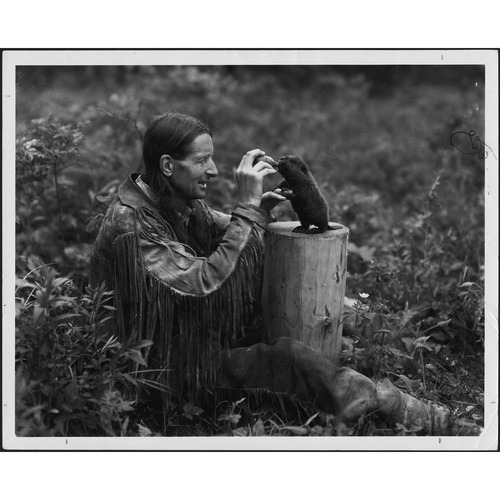

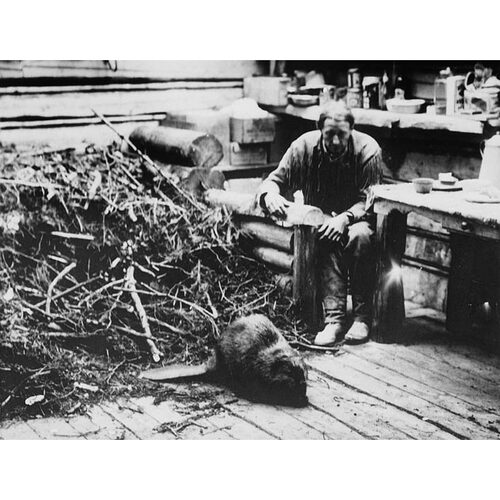

Anahareo’s plea to save two beaver kits whose mother they had caught influenced Archie to begin his crusade for conservation. Finally, he had the opportunity to do what Ada had stressed relentlessly, to make something of his life. Anahareo initially encouraged him to write, his first published article being for the influential English magazine Country Life (London) in 1929 and the next, in 1930, for Forest and Outdoors (Kingston, Ont.), brought out by the Canadian Forestry Association. When Country Life asked for a book, he used the new name he had given to Forest and Outdoors, and the work appeared as The men of the last frontier by “Grey Owl” late in 1931. The choice of name came easily since he had imitated the hoot of an owl since his boyhood days. The publisher explained his author’s background in a note in the book: “His father was a Scot, his mother an Apache Indian of New Mexico, and he was born somewhere near the Rio Grande forty odd years ago.” So convincing was he that Anahareo herself believed that he was aboriginal.

His articles had led to his appointment in the spring of 1931 as a conservation officer, or caretaker of park animals, with the Department of the Interior’s national parks branch at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba; after six months he was transferred to Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan. During the Great Depression, a time when thousands of Canadians were thrown out of work, Archie got a job. He completed his next three books in the Prince Albert park. The “beaver man” lived at Beaver Lodge, a log cabin roughly 18 by 20 feet, on Ajawaan Lake. The beaver that he and Anahareo had tamed built their lodge both outside and inside the cabin, thanks to a connecting underwater tunnel.

From his publications, and the films that the national parks branch made with him and the beaver, Grey Owl became widely known in Canada and overseas. His popularity in Britain was phenomenal. Horatio Henry Lovat Dickson*, a Canadian who had a thriving publishing firm in London, brought out his second book, Pilgrims of the wild by “Wa-sha-quon-asin (Grey Owl),” in 1934. It told the story of how, thanks to Anahareo’s influence, he had become a conservationist. The following year his children’s book appeared, The adventures of Sajo and her beaver people (London), also a best-seller. At Dickson’s invitation he made a tour of Britain in late 1935 and early 1936. Thanks to his publisher’s promotional skills and the attraction of the message of this “Modern Hiawatha,” the four-month trip proved extremely successful. In his lectures, accompanied by his films, he told his audiences about the vast northern forests and their human and animal inhabitants. His overriding theme was: “Remember you belong to Nature, not it to you.”

His triumph in Britain brought him more publicity at home. One of his grandest moments in Canada was his talk in 1936 at the Toronto Book Fair. On the evening of 9 November the tall, hawk-faced man, dressed in buckskins and wearing his long hair in braids, addressed a capacity crowd of 1,700 people at the King Edward Hotel. He had just published his fourth and final book, Tales of an empty cabin (London, 1936). The fair’s organizers turned away 500 more people at the door. Inside, the champion of the Canadian wilderness argued in his deep and thrilling voice: “Canada’s greatest asset to-day is her forest lands. In my latest book I have attacked the average Canadian’s ignorance of his own country. He is prouder of skyscrapers on Yonge Street and the price of hogs. He can have those any time but we can’t replace the natural resources we are destroying as fast as we can.” In Canada, Grey Owl pleaded, there was no longer an overabundance of wild country and wildlife. He called for an end to the plundering of the country’s hinterland.

The price of fame was high. Although the birth of their daughter, Shirley Dawn, in August 1932 had brought much happiness to him and Anahareo, their relationship deteriorated as his mission as a conservationist became all-consuming. His young wife, anxious to have a full life of her own, found his new sedentary ways, his constant writing, excessive. Friction increasingly arose, and they parted in 1936, just after his first British tour. Later that year he married Yvonne Perrier, a French Canadian woman from Ottawa. She accompanied him on his second and final tour of Britain in late 1937; it lasted three months and included a royal command performance at Buckingham Palace. He followed this trip with a three-month tour of North America in early 1938.

The pioneer environmentalist devoted all of his physical and emotional strength to his mission. At the beginning of April 1938 he returned to Beaver Lodge, totally exhausted. Only three days later he had to be rushed to hospital. Too weak to resist what was a mild case of pneumonia, he died on 13 April, at the age of 49. He would be buried near his cabin on Ajawaan Lake. The Toronto Globe and Mail, in its obituary on 14 April, termed Grey Owl the “most famous of Canadian Indians.” The media on two continents had accepted without question his romantic story of his origins. Then the bombshell dropped. Angele Belaney came forward, claiming that she was his legal wife and that he was an Englishman. In the week after his death swift detective work on both sides of the Atlantic revealed Grey Owl’s true identity. He had no North American Indian ancestry at all. The “most famous of Canadian Indians” was really one Archie Belaney, born the son of English parents and raised in the seaside town of Hastings.

The story of Archie Belaney’s rise to international fame is remarkable. Having led a life without purpose and direction, in his forties he transformed himself. As Grey Owl, he became the prophet of a vitally important message. Sometimes individuals on the fringe of society see critical issues more distinctly than those in the centre. He saw one truth clearly, the need to work for the conservation of the environment to preserve Canada’s forests and wildlife. He was decades ahead of his time.

This article is based on the author’s full-length biography of Archibald Stansfeld Belaney, From the land of shadows: the making of Grey Owl (Saskatoon, 1990; repr. Vancouver and Seattle, 1999). The GA holds all of the research notes for the book (M 4349, M 4876, M 5703, M 5806, M 6071, M 6562, M 6578, M 6989, M 7626, M 8102, M 9151). A substantial collection of Grey Owl’s correspondence is located in the Macmillan Company of Canada fonds in the William Ready Div. of Arch. and Research Coll., McMaster Univ. (Hamilton, Ont.). Several collections at LAC are also rich sources of material on Grey Owl: the Lovat Dickson fonds (R3608-0-3, 8–11, 24); the Grey Owl fonds (R2224-0-4, 1–5); and the Prince Albert National Park fonds (R5747-38-0, 1770–71, files PA 272NC, pts.1–4). Another important source of information is the Harold John Fraser fonds (S-1.34), located at the SAB in Saskatoon. A collection of manuscript letters is contained in The green leaf: a tribute to Grey Owl, ed. [H. H.] Lovat Dickson (London, 1938). Belaney’s four books – The men of the last frontier (London, 1931), Pilgrims of the wild (Toronto, 1934), The adventures of Sajo and her beaver people (London, 1935), and Tales of an empty cabin (London, 1936) – all remain in print, more than 70 years after his death. Excellent published reminiscences of Grey Owl include the memoir by his Iroquois wife, Anahareo, Devil in deerskins: my life with Grey Owl (Toronto, 1972), and the references in [H. H.] Lovat Dickson, The house of words (Toronto, 1963). Dickson also completed the well-written biography Wilderness man: the strange story of Grey Owl (Toronto, 1973). A. G. Ruffo, Grey Owl: the mystery of Archie Belaney (Regina, 1996), is an interesting imaginative recreation by a descendant of the Espaniel family who befriended Belaney in Biscotasing after World War I. Albert Braz has written two important articles: “The modern Hiawatha: Grey Owl’s construction of his aboriginal self,” in Auto/biography in Canada: critical directions, ed. Julie Rak (Waterloo, Ont., 2005), 53–68, and “St. Archie of the wild: Grey Owl’s account of his ‘natural’ conversion,” in Other selves: animals in the Canadian literary imagination, ed. Janice Fiamengo (Ottawa, 2007), 206–26.

Cite This Article

Donald B. Smith, “BELANEY, ARCHIBALD STANSFELD (Grey Owl, Wa-sha-quon-asin),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed April 29, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/belaney_archibald_stansfeld_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/belaney_archibald_stansfeld_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | Donald B. Smith |

| Title of Article: | BELANEY, ARCHIBALD STANSFELD (Grey Owl, Wa-sha-quon-asin) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2013 |

| Access Date: | April 29, 2025 |