Source: Link

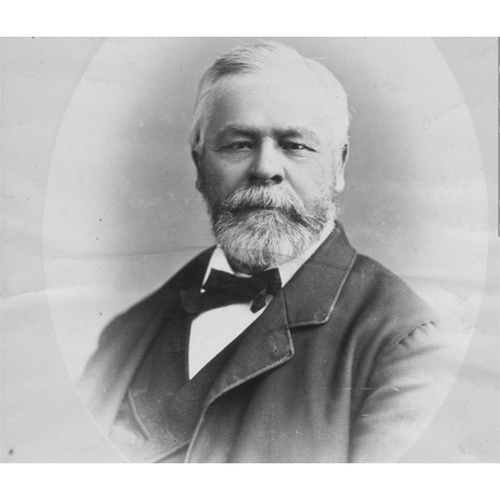

BARSALOU, JOSEPH, businessman and politician; b. 5 Dec. 1822 in Montreal, son of Joseph Barsalou, a mason, and Marie Beaupré; m. there 22 Jan. 1845 Julie-Adèle Gravel, and they had five sons and two daughters; d. 17 May 1897 in his native city.

Joseph Barsalou began his apprenticeship in business at the age of 15. Subsequently he worked for five years for Montreal auctioneer Austin Cuvillier*. In 1847 he was in the employ of Young and Benning, commission merchants and auctioneers, for whom he kept the books and occasionally served as crier at auctions. He became James Benning’s partner in 1853 and the enterprise took the name of Benning and Barsalou. It had assets of $60,000 to $70,000 by 1857, $70,000 to $80,000 two years later, and $120,000 to $140,000 in 1860. Although Benning and Barsalou invested in real estate, its main field of activity remained auctioneering. In 1860 the firm was considered the largest of its kind in Montreal.

With Peter Sarsfield Murphy and Alfred M. Farley, Barsalou in 1863 bought the British American Manufacturing Company [see Ashley Hibbard*], a rubber goods factory, which in 1866 became the Canadian Rubber Company of Montreal. That year the partners reorganized the business. James Benning, Jean-Baptiste Prat*, William Moodie, Amable Prévost, Adolphe V. Roy, Francis Scholes, William Learmont, and William D. B. Janes invested in it. Barsalou was the first president of the Canadian Rubber Company, which in 1867 began to expand rapidly when a group of financiers headed by Andrew* and Hugh* Allan invested large sums. By 1871 it was firmly established with a fixed capital of $400,000, a circulating capital of $150,000, and 370 employees. In the period 1870–1900 it captured a growing share of the domestic market, bought out competitors, and set up subsidiaries in such major Canadian cities as Toronto, Winnipeg, and Vancouver. The subscribed capital rose from $700,000 in 1878 to $1,000,000 in 1885 and $1,500,000 in 1895. Around 1870 Barsalou gave up his position as president to a director of the Allan group. Although now a minority shareholder, he nevertheless maintained commercial ties with the company. In fact, Benning and Barsalou was still auctioning damaged goods made by this factory in 1894.

In the early 1860s Barsalou went into partnership with the Dessaulles family of Saint-Hyacinthe to manage a flour-mill and a woollen factory there. In 1864 the government gave him the toll rights for the bridge he had built spanning the Rivière Yamaska, 680 feet long, 15 feet wide, and 15 feet high, which made it easier for the partners to obtain their raw materials. The enterprise expanded to some extent until 1872, when a boycott organized by wholesale merchants to protest Barsalou’s and the Dessaulles’ involvement in retail sales put an end to the firm’s activities. It was reorganized the following year with a capital of $90,000 as the Compagnie Manufacturière de Saint-Hyacinthe. But Barsalou was not among the new shareholders. He rejoined the ranks in 1874 and became increasingly identified with the Dessaulles group, participating on an equal footing with them in the rapid industrial and financial growth of Saint-Hyacinthe. In 1874 he was one of the original directors of the Banque de Saint-Hyacinthe, founded the previous year. The 30 shares he had bought in this bank for $3,000 gave him some influence on its growth and development.

Montreal nevertheless remained the central focus of Barsalou’s interests. Benning and Barsalou continued to prosper and in 1873 declared a profit of $300,000. It increasingly specialized in financing mortgages and making commercial and industrial loans. Expansion was limited, however, by restrictions on its line of credit, for the Banque du Peuple, its main source, would only grant credit of $75,000 instead of the $200,000 normally required by an enterprise of this size. This conservative policy may have been instituted because of the financial losses the company had suffered in 1874–75, when depression hit hard. Its losses rose to $250,000, nearly half being advances on merchandise never received; the firm was able to recover only a tenth of the deficit shown on its shipping charter contracts. Barsalou’s appointment to the office of auctioneer in 1876 helped it to regain some degree of financial stability.

In 1876 there were rumours in the Montreal business community that Benning and Barsalou was about to be dissolved, but it is not known whether at that time there was any substance to them. The company took on more and more the character of a family operation. Barsalou’s sons joined it in the mid 1870s. The firm kept the same name and continued to thrive until 1886, when Joseph Barsalou withdrew. His withdrawal did not affect the volume of business, but it did alter the firm’s line of credit and financial resources. Valued at between $200,000 and $250,000 from 1878 to 1883, and between $250,000 and $300,000 in 1885, these resources fell to between $10,000 and $20,000 in 1889, when Joseph’s son Arthur took over as head. In spite of the depression of the 1870s and temporary set-backs, then, Benning and Barsalou remained commercially sound. During the 1890s it still dominated its field, holding weekly auctions and big spring and fall sales at which large quantities of dry goods, footwear, and rubber articles were sold. It also continued to make its presence felt in the loan market and to purchase many valuable properties, in such locations as Rue Sainte-Catherine, Sainte-Marie and Saint-Louis wards, and the suburbs of Montreal.

The name Barsalou was also connected with a soap factory founded by Joseph and his sons around 1875. They had invested $30,000 in the construction of its four-storey premises at the corner of Rue Sainte-Catherine and Rue Durham. The Barsalous used a new technological process which they had bought for $10,000. This process eliminated nauseating odours and considerably shortened production, especially at the stages when the raw materials were mixed and ground to form a homogeneous liquid, then cooled and cut into one-pound pieces by hydraulic presses. In this way the enterprise turned out 6,000 pounds of soap in an hour and a half instead of the week required to make it by hand. Mechanization substantially reduced the cost of production. Indeed, by 1876, stamping the trade mark was the only step still carried out manually, but that too was mechanized the following year. The factory produced a million pounds of soap during its first year of operation. At that time the Barsalous were marketing bar soap for ordinary use and soap flakes for laundry under the brand names Steam Refined, Domestic, and White Olive. However, over the years they changed the names to fit Canadian conditions. The soap was sold under the labels Marseille, Universel, Cambridge, Oxford, and Imperial. The Imperial brand would become the most popular. The Barsalou soap-works adopted a horse’s head as its emblem, no doubt because Barsalou liked the animal. (In 1873 he and Andrew Allan had set up a company to promote and carry on the breeding of horses imported from Europe.) Barsalou had a life-size horse’s head made of soap for a commercial exhibition in 1880. Imperial soap even had that emblem stamped on it. The Barsalous’ original marketing strategy evolved in the ensuing period. During the Colonial and Indian Exhibition at London in 1886, they exhibited soaps with a red and blue marbled effect. In 1891, more aware of the national identity of its product, the firm had two large busts of soap made of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir Antoine-Aimé Dorion.

In 1888 Barsalou officially handed over management of the soap factory to his sons Hector and Érasme. This industrial legacy was not the only one they would receive. Indeed, all through the 1870s and 1880s Barsalou had become involved in other sectors. As a partner in a group of businessmen headed by Andrew Allan, he had helped found the Dominion Oil Cloth Company in 1872, becoming one of its shareholders. This enterprise got off to a slow start, but later captured much of the domestic market. Thus from 1878 to 1894 it doubled the subscribed capital of $100,000 and increased production capacity by grouping six factories at the corner of Rue Sainte-Catherine and Rue Parthenais.

Barsalou’s other enterprises were not as successful. The Dominion Glass Company, founded after 1885, showed a modest rate of growth. Joseph soon handed over its management to his son Maurice, retaining only the right to oversee decisions. It was Joseph who acted as its principal intermediary with the Merchants’ Bank of Canada, which provided the line of credit needed for production and marketing. In 1897 the firm owed the bank $41,000 and mortgaged various properties, but apparently that was not enough, for the company was taken over by one of its rivals early in the 20th century.

Barsalou’s venture into the slaughterhouse business was not much more successful. The Montreal Abattoir Company, incorporated in 1880 with an authorized capital of $200,000, never really got off the ground. Although he was its first president, it yielded minimal returns, at least if one relies on the evaluation of the Bradstreet credit agency. On the other hand, the Royal Canadian Insurance Company, incorporated in 1873, represented a better investment for Barsalou. He was a founder, shareholder, and in 1876 director of this enterprise, which is thought to have gone out of business or to have been taken over in the late 1880s. The Montreal Terra Cotta Lumber Company, a tile factory founded in 1887 by Alphonse Desjardins*, Barsalou’s son-in-law, escaped his influence to some extent, although he was one of its leading shareholders.

Barsalou also took an interest in municipal politics. In 1873 he ran for alderman in Saint-Louis ward against Ferdinand David*. He waged a hard-fought campaign, accusing his opponent of speculating on various occasions and of making use of patronage as chairman of the roads committee. But Barsalou himself was not above reproach. Doubts were expressed as to the evaluation he had made of a property which had been expropriated by the city in order to create the Parc du Mont-Royal. He lost the election by only 62 votes. In the early 1880s he opposed a plan to annex Hochelaga to Montreal. When it was carried out three years later, he persuaded the government to create the municipality of Maisonneuve, which took in the eastern part of Hochelaga. Barsalou then became a booster of his town. As mayor of Maisonneuve from 1884 to 1889 and from 1890 to 1892, he laid the foundations on which the town was to develop.

Joseph Barsalou seems to have been a shrewd businessman unafraid to take risks and able to attract the right people to work with him. His partnerships with the Allan and Dessaulles families illustrate his achievements well. An entrepreneurial spirit and links to a commercial network enabled him to assert himself as a French Canadian businessman. There is but one universal principle in business – success – and in this respect Barsalou more than made the grade. On many occasions he ranked near the top in matters of industrial and financial innovation.

AC, Montréal, Minutiers, Narcisse Pérodeau, 25 août 1879; 27 mars, 10–11 avril 1888; 12 avril, 16 mai 1897. ANQ-M, CE1-51, 6 déc. 1822, 22 janv. 1845, 20 mai 1897. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada (mfm. at NA). NA, RG 31, C1, 1871, Montreal. Private arch., P. M. Barsalou (Montréal), Dossier Joseph Barsalou; Marc Pelletier (Montreal), Dossier Joseph Barsalou. Bradstreet Commercial Report, ed. John Bradstreet (New York), 1878, 1881, 1883, 1885, 1887, 1889, 1895. Can., Prov. of, Statutes, 1860, c.119; 1863, c.24; 1864, c.104; 1866, c.111. Can., Statutes, 1873, c.99. Montreal illustrated, 1894 . . . (Montreal, [1894]), 141, 186–87. Que., Statutes, 1888, c.114. Le Bien public (Montréal), 18 mars 1876. Gazette (Montreal), 13 April 1876. La Minerve, 17 mars, 20 oct. 1873; 16 sept. 1880. Montreal Herald, 8 Feb. 1873; 13, 17 April 1876. Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, 28 April 1887. Montreal Witness, 25 Jan. 1873, 16 July 1875, 13 April 1876. Le National (Montréal), 10–11, 17–18, 24 févr., 3 mars 1873. L’Ordre (Montréal), 22 août 1866. La Patrie, 14 sept. 1880. La Presse, 17 mai 1897. Le Progrès (Sherbrooke, Qué.), 9 nov. 1877. F. W. Terrill, A chronology of Montreal and of Canada from A.D. 1752 to A.D. 1893 . . . (Montreal, 1893), 175, 200. Émile Benoist, Monographies économiques (2e éd., Montréal, 1925). Jean Benoit, “Le développement des mécanismes de crédit et la croissance économique d’une communauté d’affaires; les marchands et les industriels de la ville de Québec au xixe siècle” (thèse de

Cite This Article

Jean Benoit, “BARSALOU, JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed November 23, 2024, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barsalou_joseph_12E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barsalou_joseph_12E.html |

| Author of Article: | Jean Benoit |

| Title of Article: | BARSALOU, JOSEPH |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1990 |

| Year of revision: | 1990 |

| Access Date: | November 23, 2024 |