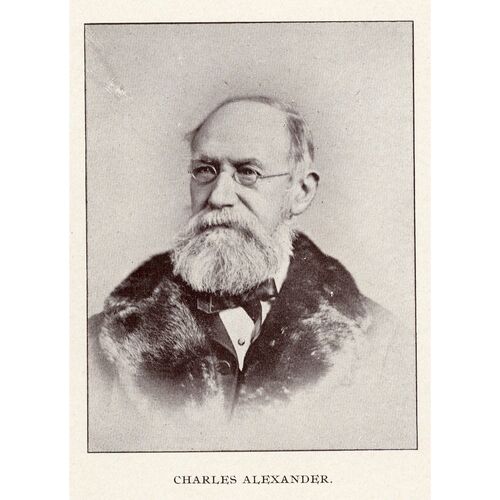

ALEXANDER, CHARLES, confectioner, caterer, philanthropist, politician, and jp; b. 13 June 1816 in Dundee, Scotland, son of John Alexander and Murina Mudie; m. first 1838 Margaret Kyle in Dundee, and they had five sons and two daughters; m secondly 22 May 1884 Mary Ann Patton in Montreal; d. there 5 Nov. 1905.

Charles Alexander was educated at the Dundee Parochial Grammar School and then was apprenticed to the firm of Keiller and Sons, marmalade manufacturers. He immigrated to Lower Canada in 1840 with his wife and son and found employment with the Montreal branch of the Keiller firm. In 1841 he left to form a partnership with H. J. Mathewson in London, Upper Canada, but he returned to Montreal the following year. After working for a few months as a journeyman, he set up his own confectionery shop with the help of borrowed capital.

Through careful management and long hours of work he built up a successful manufacturing firm and wholesale-retail business. He opened Montreal’s first temperance dining-room in 1842, to which he later added an ice-cream parlour, and he pioneered catering services in the city. By 1858 credit agents pointed to his business as the best of its kind in Montreal. Popularity led to expansion, and he moved into larger premises several times. By 1871 he had introduced steam power; near the end of the century he opened a second establishment. During his years in business Alexander trained several male apprentices and two of his sons, but most of the employees (there were 10 in 1861) were women. In 1896 he handed the firm over to the two sons.

An industrious and honest businessman whose investments were limited to his company, a small amount of real estate, and stocks, Alexander was not involved in the major commercial developments in Montreal. He is important as a reformer and philanthropist rather than as a successful, self-made businessman. Not as wealthy as many of the city’s élite, he gave of his time and skills in management instead of money to a wide variety of charitable institutions and reform causes. His life was a model of applied Christianity.

His civic involvement began in 1865 when he was elected to represent the West Ward. The vote – 147 to 0 – was an early indication of his popularity. As councillor from 1865 to 1867 and as alderman from 1868 to 1875, he sought to improve the welfare of Montreal’s citizens. He sat on the health and finance committees of the city council and was chairman of the finance committee when he resigned. He was also a member of the Citizens’ League of Montreal and the Montreal Sanitary Association. While on council he developed a life-long interest in prison reform. He lobbied the council, the police, the Legislative Assembly, and parliament for improvements and travelled to Boston and New York to investigate prison systems in the United States. He and other concerned citizens successfully pressed the federal, provincial, and municipal governments for legislation which radically altered the prison system by emphasizing rehabilitation and by creating separate facilities for juveniles and women. In addition, around 1871 he was named a justice of the peace.

On 6 Feb. 1874 Alexander was elected by acclamation to the assembly as an independent Liberal in a by-election held in Montreal Centre on the resignation of Luther Hamilton Holton*. His political career was cut short, however, when Alexander Walker Ogilvie defeated him in the general election of July 1875. Alexander continued his interest in the welfare of women and children. He was both a founding member and vice-president (1882–1900) of the Society for the Protection of Women and Children, established in 1869. The SPWC investigated cases of abuse, abandonment, and non-support and provided legal aid for women and child prisoners. In an era of unrestricted child labour, negligible efforts to ensure safety in factories, and unchallenged paternal power it lobbied for protective legislation. But its ability to bring about any real improvements was limited by a perspective which interpreted poverty as a moral issue, failed to understand the economic basis of much of working-class culture, and largely accepted the inequalities of industrial capitalism.

Alexander’s concern for women and children was also reflected in his role as chairman and honorary treasurer of the Fresh Air Fund Committee, which arranged for poor city infants and their mothers to vacation in the country; in addition, he was a trustee and incorporator in 1897 of the Sheltering Home, an asylum for single mothers and discharged female prisoners.

In 1870 Alexander and several friends tackled the problem of homeless adolescent boys by establishing the Boys’ Home of Montreal. They sought work for their boys, preferably in the skilled trades, and provided them with cheap board as well as activities such as evening classes and manual training. Alexander built the institution’s home at his own expense and was its president from 1870 until his death. During that period the home boarded more than 1,000 boys. Believing in the importance of education, in 1869 Alexander was the founding president of the Protestant Institution for Deaf-Mutes and for the Blind [see Joseph Mackay*]. A member of the board of governors of the Congregational College of British North America, he established scholarships for poor students there and at McGill College and he left his personal library to the Congregational college and the Young Men’s Christian Association.

Alexander was among the Montreal élite who formed and supported the Montreal Protestant House of Industry and Refuge. He served as a manager from its incorporation in 1863 and was its president from 1877 to 1900. Closely connected to the workhouse was the United Board of Outdoor Relief, established in 1865, which centralized non-institutional assistance to the Protestant population. Alexander sat on this committee for years and became its chairman in 1898.

His humanitarianism was broad. A member of the first committee of management for the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, established in Montreal in 1869, and its president from 1882 to 1905, he worked diligently for the protection of horses, songbirds, and dogs. He was a founding manager (1862–80), vice-president (1880–1901), and president (1901–5) of the Montreal Sailors’ Institute. His particular zeal for this work came from his own experience with shipwreck as a young man on his way to Lower Canada. He was a manager and life governor of the Montreal General Hospital from 1868 and served it as both treasurer and vice-president. A member of the Montreal Homoeopathic Association, he was its president from 1894 to 1899 and was instrumental in the establishment of the Homoeopathic Hospital of Montreal in 1894. He was also one of the original incorporators in 1881 of the Protestant Hospital for the Insane at Verdun and served on its board of governors as both vice-president and honorary vice-president. Through contributions he supported several other institutions, including the Montreal Protestant Orphan Asylum, the Montreal Ladies’ Benevolent Society, the Hervey Institute, the YMCA, and the Montreal Dispensary.

As part of the city’s social élite Alexander was a member of the Mechanics’ Institute, the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, the volunteer fire brigade, and the Art Association of Montreal. His membership in the Caledonian Society and his role as a manager of the St Andrew’s Society reflected his national origins. A devout Congregationalist, he was a deacon of both Zion and Emmanuel churches and a president of the Congregational Ministers’ Widows and Orphans’ Fund Society. During the 1870s he served as a vice-president of the Montreal Temperance Society.

A respected businessman, Alexander was a member of the Montreal Board of Trade. He served on the board of directors of the Sun Mutual Life Insurance Company of Montreal (1871–1905), the Montreal Permanent Building Society (1865–70) and its successor the Montreal Loan and Mortgage Company, and the Mount Royal Cemetery Company (1895–1905). He was also an auditor for the Montreal Workingmen’s Mutual Benefit and Widows and Orphans Provident Society (1870).

Alexander’s death occurred at age 89 when he fainted and fell from his second-storey bedroom window. His funeral at Emmanuel Church was described in a local newspaper as “one of the most impressive as well as one of the most affecting” ever to have taken place in Montreal. “Sorrowing citizens of all classes and creeds” joined the official contingents from every institution and business with which he had been associated. Funeral addresses were delivered by the Reverend Hugh Pedley of Emmanuel Church and by the Anglican archbishop, William Bennett Bond, who spoke of Alexander’s “goodness” and his “Christian life.” In response to an outpouring of sentiment the Montreal Daily Witness published a page and a half of “Incidents in a noble life,” testimonies from people Alexander had helped or who had worked with him in philanthropic endeavours. To honour the memory of one of the city’s most well-liked men, citizens donated $200,000 to erect a memorial wing at the Montreal General Hospital. The Boys’ Home of Montreal placed a memorial tablet in the new Alexander wing of the home, which he was to have opened that year.

Charles Alexander was an ideal 19th-century man – a successful businessman and humanitarian actively involved in civic welfare, prison reform, and child-saving work. His philanthropy was more personal and less symbolic than that of many members of the élite.

Numerous important notarial instruments concerning Charles Alexander are at the ANQ-M in the minute-books of Hugh Brodie (CN1-58, 1864–98), James Stewart Hunter (CN1-208, 1869–1910), and Charles Cushing (CN1-438, 1869–1910).

ANQ-M, CE1-91, 22 mai 1884. AVM, D015.22-4; D016.4; Procès-verbal du conseil municipal de Montréal, 15 févr., 13 mars 1865; Rôle d’évaluation et de perception des taxes foncières, quartier Ouest, 1904; quartier Saint-Antoine, 1883–85, 1904. Baker Library, R. G. Dun & Co. credit ledger, Canada, vols.5–7. NA, MG 24, D115; MG 28, I 129, vols.1–2; 388; 405, vol.1, files 3–21; vol.2, files 9–10; vol.3, file 1; vol.7, file 11; RG 31, C1, 1861, Montreal, West Ward. Gazette (Montreal), 6, 8 Nov. 1905; 6 March 1906. Montreal Daily Herald, 23 May 1884, 6–7 Nov. 1905, 6 March 1906. Montreal Daily Star, 6–8 Nov. 1905, 6 March 1906. Montreal Daily Witness, 6–9, 11 Nov. 1905. Atherton, Montreal. J. D. Borthwick, Hist. and biog. gazetteer; History of the Montreal prison from A.D. 1784 to A. D. 1886 . . . (Montreal, 1886). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1898). Directory, Montreal, 1842–1905. Janice Harvey, “Upper class reaction to poverty in mid-nineteenth century Montreal: a Protestant example” (ma thesis, McGill Univ., Montreal, 1978). Beatrice Johnston, For those who cannot speak: a history of the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 1869–1969 (Laval, Que., 1970). Montreal General Hospital, Annual report, 1905–13.

Cite This Article

Janice Harvey, “ALEXANDER, CHARLES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 20, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/alexander_charles_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/alexander_charles_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Janice Harvey |

| Title of Article: | ALEXANDER, CHARLES |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of publication: | 1994 |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | December 20, 2025 |

![Charles Alexander [image fixe] Original title: Charles Alexander [image fixe]](/bioimages/w600.5830.jpg)