Source: Link

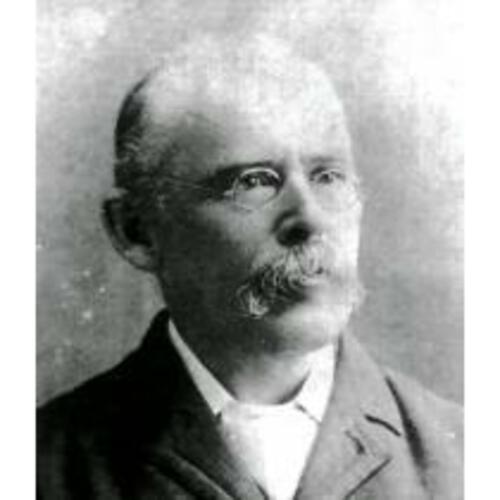

Beauchemin, Nérée (baptized Charles-Abraham-Nérée, he also signed Charles-Nérée and, more rarely, F.-C.-Nérée or C.-A.-Nérée), poet and physician; b. 20 Feb. 1850 in the parish of Sainte-Anne (at Yamachiche), Que., son of Hyacinthe (Joseph-Octave-Hyacinthe) Beauchemin, a physician and brother of Charles-Odilon*, and Marie-Louise-Elzire Richer, cousin of Bishop Louis-François Laflèche* and Sir Lomer Gouin*; m. 5 March 1878 Anna Lacerte in Sainte-Anne-d’Yamachiche (Yamachiche), and they had ten children, of whom four daughters and three sons reached adulthood; d. 29 June 1931 at Yamachiche and was buried on 2 July in the parish cemetery.

Nérée Beauchemin spent his early years in Sainte-Anne-d’Yamachiche. When he was six, he lost his mother to tuberculosis and then his brother in the space of about a month. Together with his two sisters and a remaining brother, he was entrusted to the care of his maternal grandmother. He pursued classical studies at the Séminaire de Nicolet from 1863 to 1870, winning the prize for best all-round pupil. Subsequently, he undertook medical studies at the Université Laval in Quebec City, which he completed in 1874 without honours. During this period, the only time in his life that he resided away from his birthplace, he met the writers Pamphile Le May* and Louis Fréchette*; the latter encouraged him to write verse.

Having finished his training, Beauchemin returned to Sainte-Anne-d’Yamachiche and settled in the paternal home, where he was to live and practise medicine for the rest of his life. In 1878 he married Anna Lacerte, daughter of Élie, a physician and Conservative mla and mp for the Saint-Maurice riding, and Marguerite-Louise Lami. He was fully engaged in the life of his municipality and wrote music and speeches for its celebrations and important events.

Beauchemin divided his time between his family life, profession, and writing. He published his first poem, “Les petits pèlerins,” in the 23 Nov. 1871 issue of Montreal’s L’Opinion publique. By 1931, 75 of his poems had appeared in periodicals, including Le Devoir and Le Monde illustré (Montreal), Le Courrier du Canada (Quebec City), Le Bien public and Le Nouvelliste (Trois-Rivières), Le Courrier de Saint-Hyacinthe, and L’Écho de Saint-Justin. Between 1884 and about 1906, his work mainly appeared in La Patrie.

In 1888 Beauchemin received a certificate “of encouragement” from the Royal Society of Canada, which he joined in 1896 after Fréchette proposed him for membership. To meet its requirements, he published Les floraisons matutinales (Trois-Rivières) the following year. The collection brought together 45 poems, several of which had not appeared previously, presented in no particular order. Beauchemin’s deep sensibility led him to concentrate on developing his most cherished themes: the reconciliation of the imaginary with daily life, the love of nature and homeland, faith and the sacred. Although he preferred octosyllabics to alexandrines, he composed fairly conformist poetry; it was tinged with mysticism and conventional romanticism. Because his work revealed certain Romantic influences, he appeared to be the successor to Fréchette, Le May, and Octave Crémazie*.

Despite being well received, Beauchemin’s first book met with little success in Quebec: he sold only about 20 copies. Critics in France, including Charles ab der Halden, took more notice. The author was compared to Théophile Gautier, Paul Verlaine, Louis-Sébastien Mercier, and José Marían Heredia. The French historian Albert Sorel described “La cloche de Louisbourg,” the collection’s most popular poem and the one most praised for its inspiration and spontaneity, as the “jewel of the Canadian anthology.”

Beauchemin never ceased writing; however, he consigned his poems to his desk drawer. In 1923 his friend Abbé Joseph-Gérin Gélinas, teacher and prefect of studies at the Séminaire de Saint-Joseph des Trois-Rivières, and above all a strong advocate of regional pride, tried in vain to encourage him to publish another volume. About two years later he presented the poet’s writings to his spiritual successor, Abbé Albert Tessier*, who later became an influential figure in the evolving regionalist movement. Tessier developed a friendship with the poet, whose interest in homeland, heroes, and regional history he shared. One of Beauchemin’s great admirers, Tessier supported his approach to poetry and encouraged him to write.

In discussions with the poet, Tessier learned that financial concerns were preventing Beauchemin from publishing another work; as a physician he earned a modest salary. In addition, producing his first collection had left him burdened with a few hundred dollars of debt. Tessier appealed to the provincial secretary, Louis-Athanase David*, who gave him a $300 cheque for Beauchemin and promised that the government would acquire 500 copies of any future book. It was only at Tessier’s insistence that the reserved, modest poet made the decision to publish Patrie intime: harmonies. Tessier collaborated on preparing various aspects of the volume (for example, the typography as well as the choice and organization of the poems). Published in 1928 (probably in Montreal), the collection included 78 compositions arranged in four sections: “Patrie intime,” “Au grand soleil des champs,” “Au rythme du clocher,” and “À ma plus doulce France.” Thanks to this second anthology, Beauchemin was enshrined in the history of poetry in Quebec; he was 78.

In this mature work, Beauchemin broaches the same broad themes as those of Les floraisons matutinales: his attachment to his rural milieu, its traditions and its history, and the joy and happiness of a peaceful existence flourishing in familiar surroundings. He transcends these themes, however, by using a more personal style, which unifies the collection. Nature, religion, and everyday activities are evoked simultaneously. He goes deeper into the symbolism of the sacred, bringing to mind the French symbolists, such as Verlaine. Described by several critics as a transitional poet, Beauchemin departed from the social- and philosophical-themed poetry of the Quebec school [see Octave Crémazie] and developed a musical quality associated with the École Littéraire de Montréal [see Gonzalve Desaulniers; Georges-Alma Dumont]. This new poetry presaged that of Alfred DesRochers* and Paul Morin.

On 11 November, only a few months after the release of this final collection, the poet was honoured at a grand ceremony in Trois-Rivières. The Cercle Ozanam of the Association Catholique de la Jeunesse Canadienne-Française [see Joseph Versailles] awarded him the Grand Prix d’Apostolat Laïque for poetry, and the Université Laval conferred an honorary doctorate. Two thousand people attended, including such distinguished guests as the abbés Camille Roy* and Émile Chartier*. The next day’s edition of Le Nouvelliste described the event as “the apotheosis” of “our greatest regional and national Catholic poet.” The following year Beauchemin received the Médaille de Vermeil du Prix de la Langue Française, awarded by the Académie Française, and a diplôme de maître from the Académie Florimontane in France.

Tessier probably organized these tributes to circulate Beauchemin’s work and, at the same time, promote regionalist ideas. In an article published in the Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, the historian René Verrette stated: “Gélinas was the immediate precursor [of regionalism] in laying out the ideological foundations of the concept; Beauchemin embellished them with the magic of poetry. Tessier, for his part,… labelled this ideology regionalism, humanized it and, above all, disseminated it at all levels of the population.” Armand Guilmette, author of the first critical study of the poet, would declare in 1972 that Patrie intime was “Beauchemin’s best book, and also, perhaps, the best of all regionalist literature.”

On 23 June 1931 Le Devoir published “Le pain bénit,” Beauchemin’s final poem; he died six days later at the age of 81 in his birthplace, his homeland. He received various posthumous tributes. In 1952 Yamachiche named a street after him, and in 1978 his house was added to the list of Quebec’s cultural sites. In addition, Trois-Rivières included his name on a monument honouring five men of letters, which was erected in the park near the town hall, and also named a street and a university building after him. Streets in Quebec City, Lévis, La Tuque, Amqui, and Sherbrooke also bear his name.

A solitary, quiet, dutiful man, Nérée Beauchemin wrote poems while working as a physician. Employing a personal, intimate tone, he expressed in his literary output a profound love of homeland, religion, family, the land, and nature. Having been constantly encouraged by Gélinas and Tessier, he found fame late in life with Patrie intime. Distanced from literary movements, he remained “first and foremost himself,” as Guilmette wrote in his doctoral thesis: “Nérée Beauchemin knew how to express artistically and with complete sincerity all the charm attached to time-honoured things. Therein lies all his merit and his true nature.”

Nérée Beauchemin’s two collections, Les floraisons matutinales and Patrie intime: harmonies, represent only a third of his works. He also wrote 75 pieces that appeared in periodicals, 141 unpublished poems, 16 posthumously published poems, some 100 letters, personal notes, 3 critiques, special addresses, and many fragments and versions of his writings.

In 1950, the centenary of Beauchemin’s birth, Clément Marchand* published Choix de poésies de Nérée Beauchemin (Trois-Rivières) in honour of his mentor and then, seven years later, Nérée Beauchemin (Montréal and Paris), another selection of the poet’s writings. In 1973–74 Armand Guilmette published Nérée Beauchemin: son œuvre (Montréal), the first critical edition, in three volumes, of all of the poet’s texts; this work is based on Guilmette’s doctoral thesis, “Édition critique des œuvres complètes de Nérée Beauchemin,” submitted to the Univ. Laval in 1968. In 2000 the Montreal publisher Les Herbes Rouges released Patrie intime et autres poèmes, a collection of poems selected and presented by Marchand.

BANQ-MCQ, CE401-S52, 1er mai 1848; 21 févr. 1850; 5 juin, 14 juill. 1856; 5 mars 1878; 2 juill. 1931. Le Devoir, 30 juin 1931. Le Soleil, 25 nov. 1981. Charles ab der Halden, Études de littérature canadienne française, introd. par Louis Herbette (Paris, 1904). I. A. Arnold, “Nérée Beauchemin, poète de transition,” Rev. de l’univ. d’Ottawa, 42 (1972): 279–93. DOLQ, 1: 273–75. Armand Guilmette, “Nérée Beauchemin, poète de la conciliation,” Académie Canadienne-Française, Cahiers (Montréal), 14 (1972): 131–38. Clément Marchand, Nérée Beauchemin, “Nérée Beauchemin, parnassien-mystique (1850–1931),” Qui? (Montréal), 1 (1949–1950): 65–80. Gilles Marcotte, “Les poètes qu’on ne lit pas …,” L’Action nationale (Montréal), 37 (1951): 56–57. [Albert Sorel], “Discours de M. Albert Sorel,” dans Léon Le Clerc, Champlain, célébré par les Normands et les Canadiens : mémorial des fêtes données à Honfleur les 13, 14 & 15 aout 1905 (Honfleur, France, 1908), 48–55. René Verrette, “Le régionalisme mauricien des années trente” (mémoire de ma, univ. du Québec à Trois-Rivières, 1989); “Le régionalisme mauricien des années trente,” RHAF, 47 (1993–94): 27–52.

Cite This Article

In collaboration with Katia Stockman, “BEAUCHEMIN, NÉRÉE (baptized Charles-Abraham-Nérée) (Charles-Nérée, F.-C.-Nérée, C.-A.-Nérée),” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/beauchemin_neree_16E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/beauchemin_neree_16E.html |

| Author of Article: | In collaboration with Katia Stockman |

| Title of Article: | BEAUCHEMIN, NÉRÉE (baptized Charles-Abraham-Nérée) (Charles-Nérée, F.-C.-Nérée, C.-A.-Nérée) |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 16 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 2022 |

| Access Date: | January 22, 2025 |