Source: Link

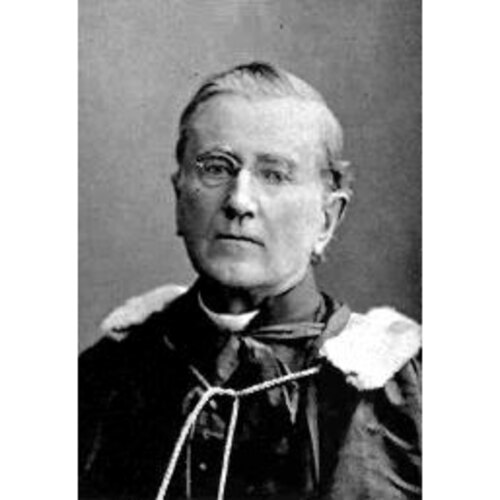

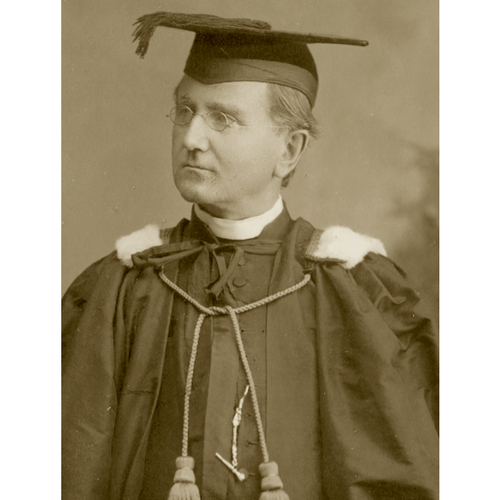

TANGUAY, CYPRIEN, Roman Catholic priest, office holder, author, and historian; b. 15 Sept. 1819 at Quebec, son of Pierre Tangué, a mason, and Reine Barthell; d. 28 April 1902 in Ottawa.

Cyprien Tanguay attended elementary school at Quebec. When he was just ten years old, he was enrolled in the recently founded Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière to begin his secondary education, but he stayed there only three months. He then entered the Petit Séminaire de Québec, from which he graduated in 1839. Upon his ordination to the priesthood on 14 May 1843, following theological studies in the city of his birth, Abbé Tanguay began an extremely active career. He served as curate in Sainte-Luce, Trois-Pistoles, and Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski (Rimouski) (December 1843 to 1846), and as curé in Saint-Raymond (1846–50), with the added responsibility of Saint-Basile from 1847 to 1849, Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski (1850–59), Saint-Michel near Quebec (1859–62), and Sainte-Hénédine (1862–65).

In every parish where he ministered, Tanguay earned a reputation as a builder, a man of action who along the way sometimes aroused strong opposition. In Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski, for example, the plan to build a majestic and costly stone church on the site where the court-house now stands was vigorously opposed by a group of parishioners. His stay at Saint-Michel was as brief as it was stormy. Perhaps it was cut short because, after completing the new church, he put the old church up for sale at auction. For whatever reason, a few parishioners made life very difficult for him, even going so far as to make direct accusations against him. He wrote to the archbishop of Quebec and asked for a transfer.

As an administrator, Tanguay may have been authoritarian, extravagant, tactless, and unwilling to listen to those around him, or he may have been simply misunderstood and disliked. Not only did he experience difficulties during his lifetime, but posterity has not always appreciated his various efforts. The case of the Collège de Rimouski is a particularly good example. His status as founder has been disputed, and animated debate has persisted through generations of diocesan priests and students at the institution, who have striven to promote the respective merits of the two claimants to the title, Abbé Tanguay and Abbé Georges Potvin.

Tanguay wanted to obtain a thorough and practical education for the young people in his parish of Saint-Germain-de-Rimouski. On 12 Jan. 1854 he sent the archbishop of Quebec a Prospectus du collège industriel en contemplation en cette localité. He explained: “Nine-tenths of the students who leave this institution will in fact be heading for farming, applied arts, business, and navigation. . . . Since this course is not to be longer than five years, it will enable a schoolboy of modest means to get a practical education, which after that time will secure him a decent living.” The other students were to pursue literary studies leading to the priesthood or to professional careers.

The college proved, however, but a pale reflection of its originator’s ideal. In 1859 inspector Georges Tanguay noted, “There is in Rimouski . . . an industrial college where the teaching is like that of a good ordinary school, no more, no less.” Tanguay’s achievement would remain an ordinary village school until late in 1861, when Potvin, curate of the parish of Saint-Germain, intervened. As chairman of the school board, he asked permission to use the sacristy of the former church, which was unoccupied. He remodelled it, largely by himself, and became the principal of the institution, taking charge of its spiritual and temporal administration as well. In 1863 the curriculum used since 1855 was broadened to meet the needs of the people. Thus the study of Latin was gradually introduced, year by year, after much resistance from Bishop Charles-François Baillargeon*, the administrator of the archdiocese of Quebec, who was under heavy pressure from the colleges at Quebec and Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière (La Pocatière).

Tanguay deserves credit for attempting to set up an educational institution relevant to regional requirements. Perhaps he hoped to have it pave the way, in due course, for a classical college. His admirers gave this idea strong support. Abbé Potvin also had his partisans. In the event the entire population of the region benefited from the sustained efforts of both men.

Although Tanguay’s claim to the title of founder of the Rimouski college (later the seminary) may have been challenged, posterity has readily granted him another title: father of genealogical studies in French Canada. He reportedly took notes during his brief stay at the Collège de Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pocatière, when he was ten years old, that could be used some 20 years later to compile a list of its first students. “These notes,” as Monsignor Joseph-Clovis-Kemner Laflamme would point out at the time of Tanguay’s death, “also contained a list of all the students, class by class, [and one] of all the teachers, priests, and seminarians, in short, the whole staff of the college, perhaps even the servants.” His calling as a statistician had been established.

In 1865 Tanguay left the parish of Sainte-Hénédine and at the request of Thomas D’Arcy McGee*, the minister of agriculture, immigration, and statistics, he accepted a position in the department as assistant with the responsibility to “set up civil and religious statistics dating from the earliest days of the country.” Joseph-Charles Taché*, a Rimouski doctor who was the deputy minister, probably had something to do with his appointment. For Tanguay, it was the start of a second and highly productive career that would span 35 years. In 1871 he published in Montreal the first volume of what would be his life’s work and his greatest achievement, the Dictionnaire généalogique des familles canadiennes depuis la fondation de la colonie jusqu’à nos jours. He had undertaken this task, which his introduction to the work described as “so vast and fraught with so many difficulties,” for an “eminently national” purpose. His serious research would facilitate the preparation of genealogical trees from which the church could establish precisely the family relationship that sometimes existed between future spouses. Marriage annulments and other extremely embarrassing situations could thereby be avoided. The dictionary also aimed to annotate parish registers or sometimes even to be a substitute for them, as well as to coordinate court records and in many cases even complete them. Since the authority of the dictionary was on a par with parish registers, Tanguay’s work assisted government officials in settling certain estates and aided magistrates in supplying legal proofs when registers were missing. Tanguay hoped that his work would be instrumental in safeguarding archives, and would contribute significantly to historical research by shedding new light on the origins of New France. “I even dare hope,” he explained, “that it will give rise to more than one interesting study on a host of questions, such as progress, emigration, population growth, vitality, and public morality.”

To compile this genealogy of Canadian families Tanguay systematically examined the parish records of the country, indeed, of the whole of French-speaking North America, copying entries of baptisms, marriages, and burials. During his lengthy journeys through continental Europe he was able to examine in detail the holdings of strategic archives, such as the Dépôt des Archives de la Marine in Paris and collections in Belgium, Prussia and other German states, and Italy. He also consulted other complementary sources: the various census reports, which were often highly detailed; works on Canada, such as the writings of Samuel de Champlain*, Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix*, Étienne-Michel Faillon*, and Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Ferland*. He assembled the information about each family on a separate form. By 1890, when the seventh and final volume was published, his dictionary would include 122,623 forms, with an average of ten documents or dates listed on each.

That such a colossal task required the author to have a methodical mind and exceptional strength of character is understandable. Tanguay was none the less the target of much criticism, even in his lifetime. He admitted there were gaps in his work, but at the same time noted the physical and intrinsic difficulties with which he had had to contend: “If I was unable to avoid all error, that is because it was impossible to do so, and I deserve some consideration after all the efforts I have made.” Tanguay’s successors have readily made these allowances, even going so far as to point out, as Joseph-Aimé-Arthur Lebœuf does in his Compliment au dictionnaire généalogique Tanguay, that “researchers and experienced genealogists know that in genealogy nothing is complete and there is always more to add.” René Jetté, the author of the most recent study designed to revise Tanguay’s material document by document and family by family, notes: “His work, now a century old, is still as admirable as monumental, not only for the scope of the information, patiently collected under arduous conditions of accessibility, lighting, and transportation, but also for the undeniable and unflagging stimulus it has given to genealogical research in Quebec.”

Cyprien Tanguay’s extensive research led him to produce other works of a more modest yet none the less useful kind. These include Répertoire général du clergé canadien, par ordre chronologique depuis la fondation de la colonie jusqu’à nos jours (Québec, 1868); Monseigneur de Lauberivière, cinquième évêque de Québec 1739–1740; documents annotés (Montréal, 1885); and À travers les registres (Montréal, 1886). But in the final analysis Tanguay’s reputation rests on an undertaking that produced genealogical and demographic studies of a scientific calibre difficult to achieve in the 19th century. This accomplishment is greatly to the credit of an individual who, although somewhat inclined to be quarrelsome and vain, nevertheless devoted his working life to the church and to his country. For this dedication he received during his lifetime many honours and numerous marks of recognition, which must have compensated him for his immense labour and for the criticism he encountered. He died in Ottawa at the age of 82. His funeral was held at the Séminaire de Québec on 2 May 1902 and his remains were placed in its chapel.

Cyprien Tanguay donated his manuscript entries for the Dictionnaire généalogique to the ASQ in 1890. The archives also holds a number of letters by members of his family and other correspondents, mainly in Polygraphie, LX, LXIV, and LXVI.

Most of Tanguay’s works have been reprinted or issued in subsequent editions. The first volume of the Dictionnaire généalogique, for example, was reprinted in Baltimore, Md ., in 1967, and the full seven volumes in New York in 1969 and in Montreal in 1975. À travers les registres was reprinted in Montreal in 1978, and a second edition of the Répertoire général du clergé canadien was issued at Montreal in 1893.

A pamphlet signed Félix and entitled Le collège de Rimouski; qui l’a fondé? (Rimouski, Qué., [1867?]) has been attributed to Tanguay and Benjamin Sulte*.

AC, Québec, État civil, Catholiques, Notre-Dame de Québec, 2 mai 1902. ANQ-Q, CE1-1, 16 sept. 1819. AP, Saint-Germain (Rimouski), Reg. des délibérations de la fabrique, 1853–67. Arch. de l’Archevêché de Rimouski, 355.106 (paroisse Saint-Germain); 419.101 (Cyprien Tanguay). Private arch., Noël Bélanger (Rimouski), Noël Bélanger, “Le prêtre-éducateur du collège-séminaire de Rimouski, 1855–1940” (typescript). H.-A. Bizier, “Le père ‘racines’ . . . ,” L’Actualité (Montreal), 15 déc. 1990. M.-A.Caron et al., Mosaïque rimouskoise; une histoire de Rimouski (Rimouski, 1979). [Fortunat Charron], Séminaire de Rimouski; fêtes du cinquantenaire, les 22 et 23 juin 1920 (Rimouski, 1920). Cyclopædia of Canadian biog. (Rose and Charlesworth), vol.1 . DOLQ, vol.1. Alphonse Fortin, Album des anciens du séminaire de Rimouski (Rimouski, 1940). Charles Guay, Chronique de Rimouski (2v., Québec, 1873–74). René Jetté, Dictionnaire généalogique des familles du Québec (Montréal, 1983). [J.-C.-K.] Laflamme, “Le ‘Dictionnaire généalogique,’” BRH, 8 (1902): 238–41. Adrien Laurendeau, Notes bio-bibliographiques sur Mgr Cyprien Tanguay (thèse de bibliothéconomie, univ. de Montréal, 1949). J.-[A.-]A. Lebœuf, Complément au dictionnaire généalogique Tanguay (3 sér., Montréal, 1957–64). Le Jeune, Dictionnaire. Le “Livre de raison” du séminaire de Rimouski, 1863–1963; images du passé, promesses d’avenir, Armand Lamontagne, édit. ([Rimouski?, 1964?]). M.-A. Roy, Saint-Michel-de-la-Durantaye; notes et souvenirs, 1678–1929 (Québec, 1929), 109. [L.-]-P.-[-R.] Sylvain, Le collège industriel de Rimouski (Rimouski, 1903); De la fondation du collège de Rimouski et de son fondateur (Rimouski, 1903).

Cite This Article

Noël Bélanger, “TANGUAY, CYPRIEN,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed January 22, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tanguay_cyprien_13E.html.

The citation above shows the format for footnotes and endnotes according to the Chicago manual of style (16th edition). Information to be used in other citation formats:

| Permalink: | https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tanguay_cyprien_13E.html |

| Author of Article: | Noël Bélanger |

| Title of Article: | TANGUAY, CYPRIEN |

| Publication Name: | Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13 |

| Publisher: | University of Toronto/Université Laval |

| Year of revision: | 1994 |

| Access Date: | January 22, 2025 |